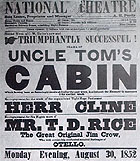

Intriguingly, Garrison was lavishing his kudos, not upon the first stage adaptation of Mrs. Stowe's classic, but the third since the novel was first published in March 1852. Several months before the release of the novel, on January 5, 1852, the first adaptation, Uncle Tom's Cabin, as it is; or, the Southern Uncle Tom, had appeared at the Baltimore Museum, followed in August of that year by a version by C. W. Taylor at Purdy's National Theatre in New York (Figure 1). Both were severely truncated, with Taylor's version running only one hour and eliminating all of the St. Clare, Eva and Topsy episodes while adding numerous songs and tableaux. According to Sarah Meer, "Taylor's was a typical sensation melodrama, an afterpiece meant to fill a space in a program rather than to cause controversy. It played on different nights alongside a nautical drama, a tightrope walker, and a blackface burlesque of Otello."* Predictably, the Taylor Uncle Tom, which was widely dismissed as "an exaggerated mockery of southern institutions calculated to poison the minds of our youth with the principles of abolitionism," closed after just 11 performances.*

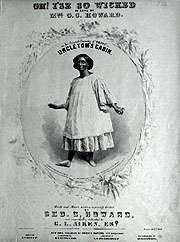

These trial ventures not withstanding, the true history of Uncle Tom on stage began with the third adaptation; a four-act drama subtitled Life Among the Lowly, that opened on September 27, 1852, not in New York, as might have been expected, but at the Troy Museum in Troy, New York, 150 miles from America's emerging theatre capitol in Manhattan. This version, which would feature the famed Howard company of actors and which ended with the death of Little Eva, was created in just one week by George Aiken (Figure 2), an actor with the company and the cousin of company manager, G. C. Howard. According to legend, Howard wanted a star vehicle for his four year old daughter, Cordelia (Figure 3). As Little Eva, and later as Little Katy, in the Howard Company version of Little Katy, or the Hot Corn Girl, Cordelia Howard defined and gained immortality as the martyred child of the Antebellum theatre.

Aiken's four-act Uncle Tom that opened in September proved so popular that by November, Aiken, spurred by audiences to "finish" the story, had added two more acts, with the play now concluding with the death of Uncle Tom and his ascendance to heaven. Just as he had done in creating his original play text, Aiken was able to work quickly on the expanded script because he simply transferred the major scenes directly from the novel and "lifted" dialogue unchanged from Mrs. Stowe's narrative. This "larceny" was logical, for, as David Grimsted has noted, . Aiken capitalized on "one of the things that most accounts for the book's success and reputation: [Namely that] Mrs. Stowe's argument is thoroughly grounded in her characters, dialogue, and incidents."* Aiken's new, six-act adaptation was as popular as his earlier drama and before it closed at the Troy Museum, it had run for 100 performances, an astonishing record considering that the long run was not yet established on the American stage and the population of Troy at the time was less than 30,000.*

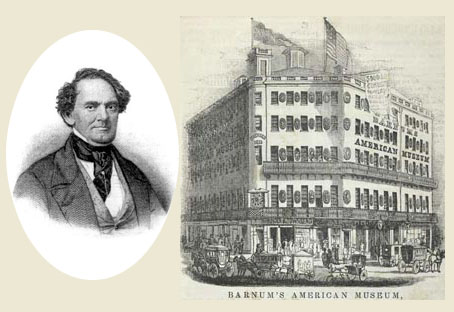

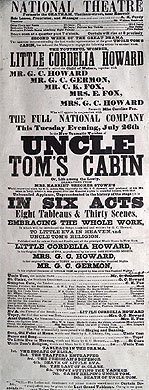

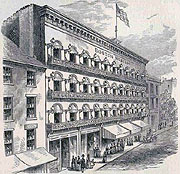

While the Aiken/Howard Uncle Tom's Cabin was running in Troy, it attracted the attention of Capt. Alexander Purdy (Figure 4), proprietor of the National Theatre in New York (Figure 5) and the producer of the ill-fated Taylor Uncle Tom earlier in the year. Undaunted by his earlier failure with the story, Purdy brought the Howard company to New York — all "six acts, eight tableaux, and thirty scenes, embracing the whole [of Mrs. Stowe's] work" — and sponsored a grand opening of the drama on July 18, 1853 (Figure 6).*

Once he had the Howard company firmly installed on his stage, Purdy took measures to ensure the financial success of his investment. While still in Troy, even though the Howards had "given a relatively straight rendering of the play . . . they had introduced an orchestral accompaniment for Eliza's flight and crashing chord accents for Legree's whiplashes, and Mrs. Howard [as Topsy] had performed a kind of 'breakdown'."* (Figure 7). In addition to retaining these "spectacular" embellishments, Purdy billed his theatre as the "Temple of the Moral Drama," he "hung the lobby with Scriptural texts and commissioned a painter to portray him with a Bible in one hand and Uncle Tom's Cabin in the other" to share the lobby with the scriptures.* At the same time, he replaced the theatre's orchestra boxes with three hundred armchairs which cost 50 cents each; he advertised comfortable accommodations in the parquet for "colored persons;" and he presented the show three times/day. Later, when competition between Uncle Tom companies in New York was at its peak, Purdy would add Jubilee singers, John Schiebel's National Brass Band and a lighting and pyrotechnic display to his Uncle Tom offerings.

Soon after Purdy's opening, four other versions appeared in neighboring theatres: one at the Bowery, a second at Barnum's Museum, a third at the Franklin Museum and a burlesque of Uncle Tom's Cabin by Christy's Minstrels. Simultaneously, adaptations of Mrs. Stowe's famous narrative were mounted in major capitals throughout the world. By October 1852, there were Uncle Toms at the Standard, the Olympic, the Strand, The Surrey and the Pavilion in London; a "translation" in Berlin; and another in Paris. In some cases, the transfer of a quintessentially American narrative resulted in a redrawing of the map of the United States. For example, the scenery of one British production "depicted Kentucky in the summer with snow-capped mountains in the background and icebergs in the Ohio River;[while] A French version had George and Eliza escaping to Canada by sailing down the Ohio in a canoe and shooting "the falls of Niagara."* George and Eliza's arrival in Canada was announced by a placard placed on the stage stating, 'Canada — Terre Libre'." However, neither the French nor the British had a monopoly on glitches; in one traveling production in a small mid-western town, the rigging got stuck as Eva ascended to heaven and as the actress dangled in mid-air, the angelic little child was heard to utter some very un-Eva-like language.

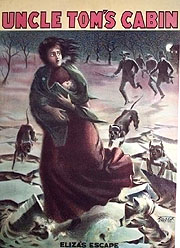

In 1853, as the Aiken/Howard/Purdy adaptation was moving toward a long run of 325 performances, productions of Uncle Tom's Cabin were staged by local stock companies in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Salt Lake City, Philadelphia and San Francisco, as well as those in New York. Of the latter, the most threatening to Purdy was the production at Barnum's Museum. Barnum had "inherited" his production from his friend and show business collaborator, Moses Kimball (Figure 8), proprietor of the Boston Museum (Figure 9). For years, Barnum and Kimball had been trading acts and shows, the most notable being the temperance classic, The Drunkard, which had debuted at Kimball's establishment in 1844 and subsequently was moved to Barnum's theatre in 1850. Kimball's Uncle Tom's Cabin had been written by noted house playwright H. C. Conway who, after being urged by Kimball and his stage manager Henry Sedley Smith, one of the co-authors of The Drunkard, to temper the "crude points" and "objectionable features" of Mrs. Stowe's novel, crafted an adaptation that came to be known as the "compromise" Uncle Tom. Conway's Uncle Tom opened with an extended plantation scene that, like the minstrel show upon which it was modeled, depicted slave life as happy and carefree; it omitted both Eliza's flight across the ice and little Harry; it accentuated the comic roles; it diminished the female ones; it allowed both Tom and Eva to live at the end of the play; and, it watered down abolitionist statements to such a degree as to render them ostensibly harmless and inoffensive to theatre patrons.