Too often the religious component of anti-slavery and abolition is investigated by focusing on ecclesiastical expressions of religion. The debates between clergymen over slavery and the struggles within denominational bodies that led to the division of the major Protestant churches into northern and southern branches have been examined extensively. Arguments over whether Biblical texts should be understood to support or condemn slavery have been thoroughly canvassed. The simple conclusion that each side could quote scripture for its own ends has been supplanted by a more nuanced understanding. We now realize that few in the early Republic believed that the Bible sanctioned slavery and that the Protestant churches generally adopted antislavery principles. As Robert Forbes has persuasively argued, the Evangelical Enlightenment produced a consensus against slavery, albeit without a program for ending it. Initially, therefore, instead of developing a proslavery ideology, Southerners defended their peculiar institution by opposing a strong federal government and an established religion, which were "the essential elements of any effective challenge to slavery," as inimical to republican principles. With the slave revolts of Denmark Vesey and then of Nat Turner and the rise of abolitionist activism in the 1830s, Southerners began to mount a defense of slavery that came to include a scriptural defense. Initially conceived as a defense of Christianity, an assurance to slaveholders that they need not abandon their religion, religiously grounded proslavery arguments had, by the 1850s, thoroughly undermined the moral consensus against slavery. The major Protestant churches had retreated from earlier antislavery pronouncements, impelling a handful of radical abolitionists to form "come-outer" splinter congregations. The antislavery consensus of the Evangelical Enlightenment had been replaced by divided churches and a scriptural debate over slavery which led contemporaries and historians to conclude that Christianity could render no decisive verdict.*

Frontispiece: Auto-

graphs for Freedom

(1853)

And yet, this essay focuses on the religious culture that produced Uncle Tom's Cabin precisely because that text — thoroughly grounded in evangelical religion — rendered a verdict that produced a political explosion. Stowe herself was acutely aware of the churches' retreat and of the ecclesiastical struggles over slavery in which her father, brothers, and husband had engaged. Yet her novel ends with a plea for the Christian church to reform, to do its Christian duty toward the enslaved, and thus to spare the nation the wrath of God's judgment on the sin of slavery. How was Stowe able to deploy religion to ignite antislavery sentiment at the very moment northen churches and clergy refused to resist the infamous Fugitive Slave law? What was the religious ground, apparently outside the churches, on which Stowe stood as she issued this call to repent and reform? To find the answer we must turn from institutional religion and explore evangelical culture more broadly in its trans- or extra-denominational dimensions. I want to do that first by sketching the theological and philosophical influences that shaped Stowe's own innovative theological imagination, and then offering an overview of the everyday practices of evangelical culture, of popular spirituality in the antebellum North in which she participated. Finally, I will turn to a brief examination of the particular gospel Stowe embedded in Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Cover: Illustrated

Edition of Uncle

Tom's Cabin (1853)

I begin with two crucial observations about evangelical religion in the antebellum years that are often overlooked by historians. First, evangelical culture was a transatlantic phenomenon with an especially vital Anglo-American connection. Print media, correspondence, friendships, travel, and international evangelical meetings bound American and European evangelicals together. Second, there was no clear line of demarcation between religion and secular culture; the separation of church and state entailed the disestablishment of religion, not the exclusion of religion from popular discourse, including political discourse. The intertwining, for example, of millennialist assumptions with notions of national progress was commonplace. Public schools purveyed Protestant principles. But disestablishment did foster both religious competition, multiplying options for evangelical consumers, and religious cooperation through the national voluntary associations, such as the American Tract Society and the American Sunday School Union, as well as a host of state and local reform and missionary societies that constituted the benevolent empire. In short, evangelical culture was fluid and porous, open to new ideas and continually generating new organizations. Simultaneously, evangelical religion was in large measure domesticated or privatized in the sense that lay religious practices complemented and frequently superseded formal worship and eluded denominational constraints.

Despite the considerable critical discussion that centers on Uncle Tom's Cabin as a product of Puritan New England, Stowe was not a Puritan or a Calvinist, although she had read her Cotton Mather and her Jonathan Edwards. She admired certain features of Calvinist culture, but rejected it as a theology unsuited to a modern, democratic age. Even the liberal, modified Calvinism of her father she had rejected as an adolescent. We know this from correspondence with her oldest brother Edward, whose increasingly innovative theological views she found comforting and compatible with her view of divinity.

Stowe's theological and moral world was shaped by a number of competing strands of thought. Scottish Common Sense philosophy, especially the moral philosophy of Francis Hutcheson and the Earl of Shaftesbury, figured prominently in the curricula at Sarah Pierce's Litchfield Academy and at her sister Catherine's Hartford Female Seminary where Stowe was educated. Texts like William Paley's Moral and Political Philosophy (1785) and his Natural Theology (1802), Bishop Butler's Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed (1736), and Archibald Alison's Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste (1790) familiarized Stowe with eighteenth-century concepts of ethics and of a moral sense closely allied with an aesthetic of moral beauty and cultivated emotions. As a school girl, Stowe also came under the influence of Romanticism through the English poets (Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron) and the novels of Sir Walter Scott.

Stowe was a young woman when her father, Lyman Beecher, moved his family to Cincinnati where he presided over the establishment of Lane Theological Seminary. Stowe's theological views matured during her Cincinnati years, from 1832-1850, as she made the acquaintance of radical religious reformers and thinkers. In Theodore Dwight Weld and the manual labor movement adherents he brought with him to study at Lane, Stowe encountered that mixture of "manual labor, abolitionism, and racial integration [that] were," Paul Goodman argues, "each expressions of a communitarian, egalitarian ethos at odds with the dominant strain of competitive individualism, an effort to balance moral values against market values." * Manual labor reforms, initiated in theological seminaries in the 1820s, linked physical health to spiritual health and prefigured the physiological reforms of the next two decades which Stowe and her family utilized in their pursuit of health. * But it was the movement's link to evangelical abolitionism that made the most profound impression on Stowe.

The famous 1834 Lane debates on slavery that Weld instigated pitted radical abolitionists against colonizationists, and ended in catastrophe for Beecher and his seminary. The trustees promulgated restrictions on student antislavery activism that encouraged Weld and his cohort to transfer en masse to Finneyite Oberlin where a new version of evangelical perfectionism developed. Stowe was not herself converted to immediatism, which called for the immediate abolition of slavery in the United States, but her sympathies for more radical antislavery were provoked. They would develop further when she and her brother Henry Ward Beecher came to the defense, on free speech grounds, of James G. Birney (the publisher of an antislavery paper in Cincinnati who would become the Liberty Party candidate for President in 1844) when a mob attacked his press in the summer of 1836. Subsequently, Birney's assistant, Dr. Gamaliel Bailey, took over publication until 1847, when he moved to Washington, D.C. to edit another antislavery paper, the National Era, which would publish Uncle Tom's Cabin to the world. The following year another religious antislavery editor, the Presbyterian minister Elijah Lovejoy, was murdered by a mob in Alton, Illinois. His story, told in a memorial published by his friend Edward Beecher, had a deep and lasting impact on Stowe's thinking about the question of slavery in a republic. Finally, in 1838 and 1839, Alexander Kinmont delivered a series of lectures in Cincinnati that articulated a racial romanticism which Stowe seems to have imbibed. She came to share his view that Africans as a race possessed spiritual gifts that made them peculiarly susceptible to the teachings of Christianity and capable of an exalted religiosity. Thus events and public debates in Cincinnati in the 1830s supplied Stowe with arguments for an evangelically based antislavery.

In more private ways, German Romantic theology began to shape her understanding of the emotional and aesthetic elements of Christian doctrine. Her knowledge of German theology was mediated through Calvin Stowe's twin passsions for Goethe's Faust (with its treatment of suffering and salvation) and for German Biblical scholarship, the so-called Higher Criticism, that historicized Biblical texts and subjected them to philological analysis. Through her husband Stowe became acquainted with Lessing and Herder as well as Schleiermacher, Schelling, and Feuerbach. Calvin developed a particular closeness to Friedrich Tholuck, an evangelical theologian and gifted linguist who was deeply influenced by Schleiermacher and by the historian August Neander (whose History of the Apostolic Church Calvin read on shipboard en route to Europe in 1836). * Calvin also reported his delight in meeting another hero, Friedrich Creuzer, author of Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Völker (1810).*

We know from their letters that Harriet and Calvin shared theological views that their circle at Lane Seminary would have found shocking and heretical. "I have been thinking this week how much real communion of soul and spirit we have had together, notwithstanding all the little semitones[?] of married life, of which we have had our share. On matters of religion and taste our opinions and feelings, though quite independent and different from the rest of the world, are very much alike; and I believe there are very few husbands and wives in the world, who have so many real good talks together on such matters as we have. If old Richard Baxter [Puritan divine] and his wife used to lie in bed and sing psalms together for their mutual edification, I am sure some of our discourses in sheets have been not less agreeable and edifying. I wish we could have another this very night."* (This passage precedes Calvin's famous admonition to Harriet that she "must be a literary woman.") A month later Calvin writes that he wants her with him, "— want[s] to go to bed & talk about Tholuck, Dannecker, Jean Paul, Frederick William . . . . There is not a soul that I can say a word to about any of these matters, and I begin to find out, (what I knew very well before), that you are the most intelligent and agreeable woman in the whole circle of my acquaintance."*

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

What the Stowes found so congenial in German Romantic theology was its emphasis, in countering the skeptical rationalism of Enlightenment deism, on aesthetic and ethical idealism. Stowe was also aware of what American contemporaries were doing in re-fashioning Christian theology under the influence of European Romanticism. Emerson's version of transcendentalism she found too abstract. But Thoreau's essay on "Resistance to Civil Government" (1849) develops an argument that adherence to higher law may require civil disobedience, which parallels the argument for civil disobedience that Stowe offers in her narrative of Eliza's escape, especially in scenes set in Senator Bird's home and in the Quaker settlement. A letter to her sister Isabella Beecher Hooker reveals that Stowe was interested in the Coleridgean ideas promulgated by Horace Bushnell (of Christian Nurture [1847] fame), but feared that he might have pressed his notions a bit too far. ("Where do you go to church at Bushnels or Hawes[?] For my part I begin to be a little afraid that the Bushnel movement may go too far & to hold on to the old ground — that is to say when people are suddenly set loose from what they have considered to be old truths they are apt to push their freedom too far & too fast — "*) While Stowe entertained doubts about the most radical interpretations of it, German Romanticism had taught her to value the emotional apprehension of religious truth over empirical argument, and she welcomed the contributions that art and music could make in provoking the religious emotion that evangelical culture valued.

In the 1840s Stowe found herself caught up in the perfectionist turn that swept through American evangelical circles and led many to share Stowe's hope for a revitalized spirituality that could supplement if not replace the formal structures of sectarian church organization. Understandably, she and her family were skeptical of the Oberlin perfectionists, but her hunger for a revitalization of Christianity that would answer her personal spiritual longings and ignite a national spiritual revival to usher in the millennium led her to the holiness teachings of Phoebe Palmer, the Methodist lay leader whose Tuesday Meetings in New York City had converted non-Methodists as well as her denominational fellows to a belief in sanctification as a second blessing bestowed on believers.

Stowe had been deeply and favorably impressed by Thomas Upham's exposition of holiness doctrine in Principles of the Interior or Hidden Life (1843), which she reviewed in the New-York Evangelist in 1845.* Upham, a Congregationalist professor of moral philosophy at Bowdoin College, had experienced a holiness conversion under Phoebe Palmer's influence. His version of holiness played a crucial role in resolving Stowe's spiritual crisis of the early 1840's. Evidence of Stowe's holiness conversion comes from an account published by another of Palmer's non-Methodist converts, William E. Boardman, who was destined to play a major role in the holiness or higher life movement in England as well as the United States. Boardman's The Higher Christian Life (1858) describes the holiness conversion of "a lady of distinction . . . well known both in Europe and America, both by the brilliance of her genius, and the liberality of her gifts, but as she is still living her name is withheld." The details Boardman supplies leave little doubt that this mystery celebrity must have been Stowe. Boardman, then a student at Lane Seminary, and his wife had moved into the Stowe home for several months in 1844 in order to operate it as a boarding house while Calvin was travelling in the East on seminary business. Boardman would have been privy to her struggles, aware that her interest in perfectionist doctrine had been sparked by "a brother beloved" (George Beecher), that she had made repeated trials of casting herself upon Christ only to experience disappointment in the results, until

The hand of the Lord . . . at last placed upon her pillow — for she was ill at the time — Upham's "Interior Life." . . . Coming to the chapter on "Consecration," she . . . said to herself, "This I have not done. I have tried to trust in Jesus, but I have never yet in all these attempts, made an entire surrender of myself to him, to do his will, but only to receive his salvation."*

Boardman wishes to make the point that consecration required yielding oneself as a living sacrifice to God, that Stowe's earlier efforts had been centered on passively consecrating herself to "receive merely, and not to do." Boardman is rephrasing a central tenet of Palmer's altar theology which required that one lay one's "all" on the altar, receive the blessing and be empowered for service. It is this theological construction that permeates Uncle Tom's Cabin.* The concept of empowerment for service, coupled with millenialist expectations, encouraged perfectionists to engage in a host of reforms aimed at perfecting the nation and hastening the millennium.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Letters written throughout the months that Stowe shared her house with the Boardmans are filled with the language of holiness doctrine. She writes of becoming "one with Christ in that union of which marriage is a type" and reminds Calvin of "God's promise to abide with us." Her letters reiterate her desire that they lead a renovated family life, that "our reunion may be an era in the history of our family from which we shall commence serving God more perfectly than ever before."* Upham's concept of union with the divine, which required the sacrifice of the will, was consonant with the spiritual experience that Stowe described in a letter to her brother Tom,

My all changed — whereas once my heart ran with a strong current to the world, it now runs with a current the other way. . . . The will of Christ seems to me the steady pulse of my being & I go because I cannot help it. Skeptical doubt cannot exist — . . . I am calm, but full.*While this state of calm did not persist, it remained her ideal. And certainly she usually seemed confident that her will was aligned with God's. Her religious views were not narrowly circumscribed by holiness doctrine, but its emphasis on mystical union with the divine and on a Christian spirituality that could not be limited by formal, institutional boundaries became a central component in her religious eclecticism.

German idealism and perfectionist theology formed the foundations of her faith, but she also dabbled in mesmerism and Spiritualism when those were popular phenomena. Ultimately, the spiritual comfort she found in art, music and ritual led her to embrace Episcopalianism in place of what she considered the aesthetic barrenness of Congregationalist services. Throughout she held to a Trinitarian conception of the divine, and — like many liberal evangelicals — her theology was Christocentric.* Stowe ultimately formulated a religious epistemology in which the divine is known through the emotions. She conceptualized this metaphorically, in The Minister's Wooing, in the famous conceit of "a ladder to heaven, whose base God has place in human affections, tender instincts, symbolic feelings, sacraments of love, through which the soul rises higher and higher, refining as she goes, till she outgrows the human, and changes, as she rises, into the image of the divine."* Her theology has been described as sentimental incarnationalism, a theology which, Thomas Jenkins argues, "emerged in the 1840s as an effort to make God more emotional and expressive" in contrast to the God of neoclassical theism whose main characteristic was serenity. According to Jenkins, "the basic difference between neoclassical and sentimental characterization turned. . . on the depiction of love. Neoclassical benevolence was a fusion of reason with love; sentimental sympathy was a fusion of pity with love. . . . God, through Christ, came close to humans in a very tactile way — 'not casting the humblest penitent away, but pressing him close to his bosom.'"* For Stowe, Christ's intimacy with human suffering and human sufferers modeled the way Christians ought to feel and respond to the manifest suffering that slavery generated.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

To delineate the culture of evangelicalism in the antebellum North, the historian must consider carefully where it operated. For this purpose, Stowe's history is illuminating. Sermons and formal worship services form a part of her religious habitus, but they are the least part. Her religious life centered on practices pursued in the privacy of domestic spaces: reading and discussion, singing and prayers. Social intercourse, in conversation and letters, was a staple of Victorian spiritual practice. Religion formed a discursive web in which evangelical life was lived. The Beecher family debated theology at the dinner table and in circular letters that kept the family connected despite geographic dispersion. They talked about the books they read and the events of the day, and aired their own decided views. Stowe's letters of spiritual advice and consolation were legendary among her family and friends, but they differ in quality rather than kind from common practice among evangelicals.

Religion also permeated print culture in the antebellum era. Religious newspapers as well as books and tracts were a primary component of the print explosion that marked the era. But the boundaries between the religious and the secular were porous indeed in print media. Religious newspapers contained news of the day as well as religious commentary, while fiction frequently treated serious religious matters. Stowe, as she embarked on a career as a writer during her Cincinnati years, published primarily in two periodicals, the Presbyterian weekly New York Evangelist and Godey's Lady's Book. The fiction she supplied to Godey's frequently contained religious and moral messages, while her contributions to the Evangelist included reviews of British novelists and poets as well as essays on religious topics and moral tales. Her contributions to the Evangelist were sometimes republished as tracts by the American Tract Society. Non-denominational publishing societies circulated religious texts across denominational boundaries. Major commercial publishers advertised lists that mixed religious works with other fare. Categorizing works as specifically religious or non-religious is not an easy or profitable task; poetry, best-selling novels and serious works of fiction alike treated religion as a part of life.

Family prayers and Bible reading were daily practices in many evangelical households. So, too, was hymn-singing. Those households without a piano in the parlor were not excluded from singing; Stowe, for example, played an accordion in the years before her family acquired a piano. Stowe's taste in hymns illustrates decisively that hymnody moved widely across denominational lines. Most of the hymns that she incorporated in Uncle Tom's Cabin have been identified as Methodist hymns, but she clearly anticipated that the antislavery audience of the National Era would find them familiar. Her preference for Methodist tunes may reflect their compatibility, grounded in Wesleyan perfectionist theology, with her own theological tendencies. But her eclecticism was musical as well as theological. She was familiar with the hymns of Isaac Watts and John Newton and with Catholic liturgical music such as Dies Irae and the Miserere as well as camp meeting spirituals.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Her taste in devotional literature was similarly eclectic. John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress was nearly as familiar to her as the King James Bible. But like many of her contemporaries, she also read the French Quietist mystics, Bishop Fénelon and Madame Guyon, whose works were available in translation in many editions in the antebellum period. Thomas ŕ Kempis' Imitation of Christ was another spiritual classic that appealed to her. She used and encouraged others to use John Keble's Christian Year, despite his association with the high church Tractarian Movement at Oxford. Her own devotional outpourings took the form of poetry and columns in the Evangelist. Two tracts from the period just before the writing of Uncle Tom's Cabin should be noted in particular. Earthly Care a Heavenly Discipline, frequently reprinted, gained a broad audience in the United States and Europe. Its argument that "were God known and regarded as the soul's familiar friend" then, by confiding in his love, "the thousand minute cares and complexities of life become each one a fine affiliating bond between the soul and its God" presages the theology of suffering that emerges in Uncle Tom's Cabin. On the Ministrations of Departed Spirits in This World, published in1849 in the immedate wake of reports of the Fox sisters' spirit rappings, offers a cautious argument for the possibility and plausibility of departed friends watching over one. Stowe's openness to such spiritual phenomena is evident in the visions of Eva and Christ that appear to Tom toward the novel's end. Her own letters record visionary experiences during pre-dawn meditations in a dream-like state. Calvin Stowe had a decided propensity for visions throughout his life. Their letters to each other contain interpretations of such religious dreams and visions.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Stowe also poured over volumes on religious art. Her European travels, made possible by the fame and modest fortune that Uncle Tom's Cabin brought her, were art pilgrimages as they were for many bourgeois American tourists. Stowe's views on religious art were guided by English critics, especially Anna Jameson and John Ruskin. But Uncle Tom's Cabin reveals that long before she enjoyed the opportunity to see Europe's treasures of religious art and architecture for herself, Stowe appreciated the power of art to teach religious lessons. The novel itself was her tract on slavery, illustrated by paintings in prose, since she believed that "There is no arguing with pictures, and everybody is impressed by them, whether they mean to be or not." *

Stowe's decision to cast her antislavery argument in the form of a novel measures the extent to which novels had become, for evangelical culture, a forum for the discussion of religious and moral dilemmas.* But it is equally revealing to note that this novel situates religious discussion in conversations among the laity. There are virtually no clerical characters, no religious authority granted to clerical voices. Instead, spirituality resides among slaves and Quakers, women and children, and is shown being perfected in a Southern planter and his Northern cousin as well as in Uncle Tom. The book's message circulates through the text in the ways that evangelical religion operated in antebellum culture, through protracted conversations, Biblical interpretation, hymns and prayers, visions and paintings that are located always in extra-ecclesiastical spaces. The reader is invited to listen, if not to discourses in sheets, to intimate discussions of the sort that made up the discursive web which constituted evangelical culture. In examining the gospel according to Uncle Tom's Cabin, I focus primarily on two moments: Tom's "victory" in the chapter with that title, which I read as a holiness conversion, and St. Clare's repeated allusions, in conversations with Miss Ophelia about the need to conquer racial prejudice, to a religious painting owned by his mother.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

The centrality of Thomas Upham's version of holiness spirituality to Stowe's conception of a renovated Christianity made it a matter of deep distress to her that they could come to divergent conclusions about what God willed in the matter of the Fugitive Slave statute. To Stowe, Upham was the paradigmatic example of those Northern Christians whose renewed attention to the interior life represented "a longing & a sighing for some more perfect state to be attained even in this world." If such sanctified souls could not see the issue clearly, what hope was there? Those whose spiritual force should be shaping public opinion must be shown where their religious duty lay. She proposed to use her art to paint the realities of slavery in a way that could touch the heart. In doing so, she hoped to overturn the prudent, politic calculations of humane people who, like Senator Bird in the novel, argued that the public interest must override private feeling. And she intended her narrative as a rebuke to Christians, like Upham, who managed to construe slavery as a providential institution for civilizing and Christianizing Africans who might eventually be freed and sent to evangelize Africa when that could be arranged without danger of disrupting the Union.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Stowe knew that she needed to persuade her evangelical public that abolition was a Christian imperative, not a radical, skeptical agenda. Abolitionism, in 1850, was a minority movement. Abolitionists were generally considered fanatics; the movement was composed largely of irreligious skeptics or fringe sectarians like the Quakers and perfectionist "come-outers" who left mainstream churches to form separatist congregations. Abolitionism had actually declined from its earlier peak of public support in the 1830s, although renewed opposition to the extension of slavery had been encouraged by the perception that the Mexican War was fought to open up new slaveholding territory and was further fueled by the provisions of the Compromise of 1850. Moderate and cautious anti-slavery, still a minority sentiment though more common among Northern Christians than a commitment to abolition, embraced gradualism and colonization. The majority were prepared to accept slavery as a Southern institution with which they had no right to interfere; for them, the extension of slavery was the only open political issue. Few were prepared to see it as a religious question. To persuade them to do so, Stowe knew she must counter arguments that African slavery had the beneficial effect of Christianizing heathens, that the Bible sanctions slavery, and that it is no more imperfect than any other human institution. Her appeal is to the evangelical concept of brotherhood and sisterhood. It relies on widespread acceptance in popular evangelical piety of a concept of sanctification, to make the sanctification of a black man the clinching argument for the full humanity and Christian potential of the African race.

Stowe embeds her political arguments in an emotional logic, appealing to emotions as a human capacity intimately connected, in her view, to religion and moral sense. Like the Scottish Common Sense philosophers whose conception of spectatorial sympathy was central to their understanding of the operation of the moral sense, Stowe believed that benevolence was a sentiment evoked by the spectacle of suffering. Adam Smith described the process as requiring an imaginative identification with the sufferer.

By the imagination we . . . conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them.*What Smith describes is surprisingly similar, except in its imperfect realization, to Stowe's understanding of the Incarnation. Stowe wrote of Christ's "baptism of agony in the Garden of Gethsemane," as "standing for that infinite possibility of pain which the one divine Man was to taste for every man." She connected Christ's suffering to his ability to comfort.

But he who knows what it is to suffer; he who has felt the horror, the amazement, the heart-sick dread — who has fallen on his face overcome, and prayed with cryings and tears and bloody sweat of agony — he can understand us and can help us. *Her version of holiness perfectionism, with its emphasis on union with the divine and empowerment for service, suggests that sanctified Christians, in their ability to more perfectly imitate Christ, can more fully enter into the sufferings of others than the unsanctified can. But she would have agreed with Smith's broader argument that the human imagination was intimately connected to the moral sense.

For her evangelical public, Stowe's objective was to demonstrate the African's capacity to be a fellow Christian. Tom is, of course, Stowe's prime example. The novel, on one level, is his spiritual biography. His spiritual journey, perhaps not surprisingly, bears a remarkable resemblance to Stowe's own religious history. The faith that sustains him in Kentucky, and makes him a religious leader among his fellow slaves, serves him well enough while the trial of separation from family is alleviated by the favorable circumstances in which he finds himself as St. Clare's property. But that apparently unshakeable faith is severely tested in the living hell he endures under Legree's brutal regime. Tom's religious peace and trust give way to despondent darkness. In this moment of crisis, Tom sees a vision of Christ, and falls into a trance. When he is roused, the despair has been replaced with joy. Stowe writes, in the rhetoric of holiness theology, that "he that hour loosed and parted from every hope in life that now is, and offered his own will an unquestioning sacrifice to the Infinite." From that moment on he possessed "an inviolable peace."

Past now the bleeding of earthly regrets; past its fluctuations of hope, and fear, and desire; the human will, bent, and bleeding, and struggling long, was now entirely merged in the Divine. . . . Tom's whole soul overflowed with compassion and sympathy for the poor wretches by whom he was surrounded. . . . and out of that strange treasury of peace and joy, with which he had been endowed from above, he longed to pour out something for the relief of their woes (Chapter 38).Tom has clearly experienced the second blessing of sanctification; the merger of his will with the Divine and his empowerment for service would have been clear signs to Stowe's evangelical readers. And to no one more clearly than to Thomas Upham. Tom's example of ministry to his fellow slaves is a reproach to Upham personally, and to Christians generally. His willingness to die in order to help Cassy and Emmeline escape is also a reproach to those who defended upholding the Fugitive Slave Act. His death then bears both an evangelical and a political message.

Stowe develops another line of argument by portraying the damage that slavery does to the master class. The moral threat to children is revealed in Henrique's ungovernable temper. Marie St. Clare provides an instructive portrait of the kind of monster of selfishness that slavery produced. Slavery also undermines religion among the more thoughtful of the master class. St. Clare is disgusted by the church's justifications of an institution that he despises. Mr. Wilson, George Harris's kindly employer, is torn between the proslavery religion he has been taught and his sympathetic feelings. For both St. Clare and Wilson, proslavery religion threatens the very foundation of evangelical gentility, the alignment of faith and feeling.

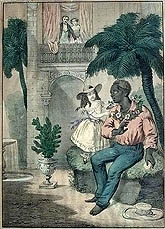

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Northern Christians have also been damaged by their willingness to deny the full humanity of the African and their unwillingness to admit them to the fellowship of Christian brotherhood and sisterhood. Stowe's religion of feeling requires an emotional intimacy, with the sufferer as well as with the suffering Christ. Emotion and touch are intricately connected in Stowe's conception of feeling in the novel. Love, both erotic and benevolent, is expressed by physical contact. Miss Ophelia's abstract commitment to anti-slavery as a moral obligation is undermined by her racial prejudice. Her physical revulsion at the sight of Eva hugging and kissing Mammy and the other St. Clare slaves displays the debilitating limit to her benevolence. Stowe's concern with racial prejudice that produces a physical recoil, and her insistence on the necessity of removing the emotional barriers against cross-racial intimacy constitute a theme in the novel that critics have largely ignored. It is also a concern that antislavery writing rarely addressed. Romantic racialism, while insisting upon the full humanity of the African, posited racial differences that supported a distanced benevolence rather than an intimate relationship, and did little to conquer racial prejudice. Through Miss Ophelia, Stowe holds such prejudice up to scrutiny, and makes overcoming it a mark of perfected spirituality. She attaches that lesson to one of the images from the novel that became, in the form of statuettes, a staple of Victorian parlor decoration. This scene shows Tom, wreathed in the flowers that Eva has draped over him, seated on a bench with the child on his knee. Miss Ophelia, witnessing this, demands of St. Clare how he can allow Eva to do so. When he asks why not, the answer is that "it seems so dreadful." Stowe allows St. Clare to challenge and analyze Ophelia's "feeling" in terms that express her understanding of the nature and pervasiveness of Northern prejudice.

You would think no harm in a child's caressing a large dog, even if he was black; but a creature that can think, and reason, and feel, and is immortal, you shudder at; confess it, cousin. I know that the feeling among some of you northerners well enough. Not that there is a particle of virtue in our not having it; but custom with us does what Christianity ought to do, — obliterates the feeling of personal prejudice. . . . You loathe them as you would a snake or a toad, yet you are indignant at their wrongs. You would not have them abused; but you don't want to have anything to do with them yourselves. You would send them to Africa, out of your sight and smell. . . . (Chapter 16)

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Stowe's explicit emphasis on the evangelical imperative to lay hands on the sufferer removes the distance that spectatorial sympathy allowed and even encouraged. Evangelical love authorizes intimacy across racial boundaries. And while it is the child who is, as St. Clare says, "your true democrat" (Chapter 16), Stowe invokes the notion that a child shall lead them to extend the pattern of evangelical intimacy to adult relations. She pictures cross-racial intimacy throughout the novel, most often signified by the image of clasped hands. Eliza puts out her hand to Mrs. Bird in parting and "a hand as soft and beautiful was given in return" (Chapter 9). At the Halliday house, Rachel lays her hand on Eliza's head, while Ruth restores her to consciousness by "rubbing her hands with camphor" (Chapter 13). Mr. Wilson and George Harris part with a hearty handshake. George Shelby and his mother both hold Aunt Chloe's hands and weep with her as she absorbs the news of Tom's death. St. Clare wrings Tom's hand as Eva struggles for her final breath; and as Eva dies, Tom clasps "his master's hand between his own; and with tears streaming down his dark cheeks, looked up for help where he had always been used to look" (Chapter 26). The intimacy that grows between St. Clare and Tom is expressed physically in repeated scenes, with tears and hand clasps, with St. Clare's head on Tom's shoulder. The intimacy between Tom and St. Clare mirrors the intimacy between Tom and Eva; Stowe even depicts an occasion when St. Clare seats himself beside Tom, on the very bench where Eva had perched on Tom's knee, and reads to him that passage from Matthew which specifies that in the final judgment people will be held accountable for failing to do positive good. St. Clare dies before he can do the positive good of freeing his slaves. But the circumstances of his death reinforce Stowe's emphasis on the radical egalitarianism of evangelical intimacy. In his dying moment, St. Clare takes Tom's hand and gazes into his eyes; then, Stowe writes, "He closed his eyes, but still retained his hold; for, in the gates of eternity, the black hand and the white hold each other with an equal clasp" (Chapter 27).

But the promise of evangelical intimacy remains unfulfilled; the sin of slavery still threatens the nation's millennial future at the novel's end. Uncle Tom's sanctification and martyrdom display the "African" capacity for perfected Christianity. Tom's martyrdom is, however, not a crucifixion in the sense that it does not atone for the sin of slavery. He has taken on not the burden of sin, but the burden of others' suffering. He saves Cassy and Emmeline from suffering/death, and enables their escape to freedom. He bears the burdens of the other slaves. But he does not atone for the sin of slavery. From a Christian theological perspective sin is the root cause of suffering. Original sin led to the ouster from Eden. Sinful humanity made the crucifixion necessary. Christ's suffering atones for sins of the saved. But to affix the label "sin," with all its doctrinal weight, to slavery as a legal and social institution was to radically expand the concept of sin; to imagine a sin beyond the power of Christ's atonement that nonetheless would draw down the wrath of God on the nation.

Stowe needed a panoramic canvas to make her most subtle and controversial theological argument, the nature of slavery as organic or social/institutional sin, a sin for which there is no atonement in Christ's sacrifice. Individuals were enmeshed in this system. Even those conscious of its moral evil were helpless as individuals to change the system. The critics who define Stowe's fiction as finally a failure because it does not "solve" the problem of slavery have missed the point that Stowe believed the system was not susceptible to individual onslaughts. Hence the need to plead for divine intervention, and to prepare the way for change by enlarging the class of people who rightly perceived and felt the weight of the evil. Evangelical reform in a democratic culture depended upon a delicate balance between individual regeneration and the collective social (and spiritual) power of a growing body of regenerated individuals within the public.

The evangelical public's ability to enact justice and mercy depends upon its political power. Here the logic of evangelical sentimentalism intersects with the logic of republican ideology. Feelings, when openly displayed, affect the actions of politicians whose careers depend upon public sentiment. Stowe's appreciation of these intersecting logics is apparent in her sketch of Sam as a consummate politician who detects Mrs. Shelby's desire to let Eliza and Harry escape, abruptly reverses his plan to prove himself by catching them, and instead contrives to prevent Haley from apprehending them. Stowe's portrayal of Sam is simultaneously an indictment of those politicians whose deficient personal moral sense had allowed them to construct the infamous Compromise of 1850, and a shrewd assessment of the power of public opinion to control political behavior. Mrs. Shelby displays privately the sentiment against slavery that derives from her Christian commitment and her sound moral sense. Mrs. Stowe's novel is a public display of private, religious feeling designed to change both feelings and policy, and a heated, intellectual argument about ideology and theology. Feeling right has a political salience that extends from evangelicals' parlors to legislative chambers.

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE