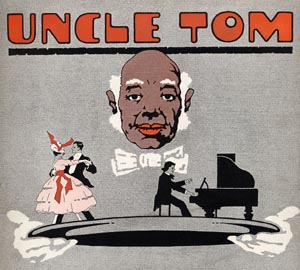

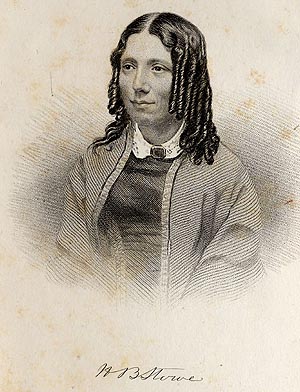

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe may have been spawned as sentimental fiction, but Uncle Tom’s story was never solely a literary event.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe may have been spawned as sentimental fiction, but Uncle Tom’s story was never solely a literary event.Uncle Tom is an enduring icon even today because he was drawn, painted, and inscribed in prints; he was embodied onstage, in photographs, and in motion pictures; his representation was continually refitted to changing social, political, and economic strategies of mainstream America.

Pictures made Uncle Tom “an Uncle Tom.”

SOURCE

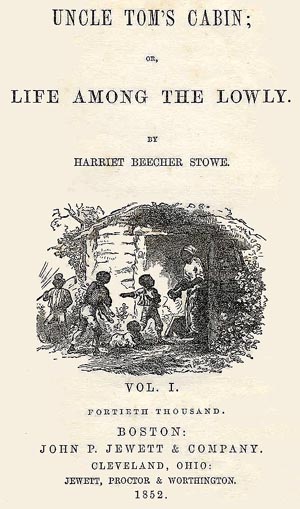

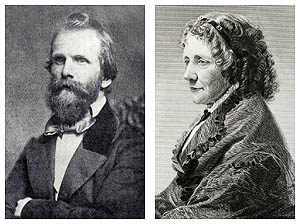

It was probably publisher John P. Jewett, who engaged an illustrator to provide the "six elegant designs,” touted in advertisements, plus title page vignette and gilt embossed cover for that original Uncle Tom’s Cabin of 1852.

Illustrations were special features in books, not common practice, especially for a first time novelist. These may have been a way to compensate for a long story that required a costly, two-volumes.* Uncle Tom’s Cabin developed from June 1851 through April 1852 as regular installments in a Washington, DC, abolitionist weekly The National Era.*

When Stowe first pitched the story to editor Gamaliel Bailey, she claimed her objective in writing a few episodes would be "to hold up in the most lifelike and graphic manner possible Slavery, its reverses, changes, and the negro character, which I have had ample opportunity for studying." As she stated, "There is no arguing with pictures and everybody is impressed with them. . ."* Stowe was an amateur artist, but she was referring to mental pictures. There is no record that she played any part in selecting the illustrator or the scenes that would become his “pictures.”

SOURCE

Hammatt Billings, better know as an architect, began his draughtsman career in the early 1840s as chief illustrator of the popular weekly, Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion.

SOURCE

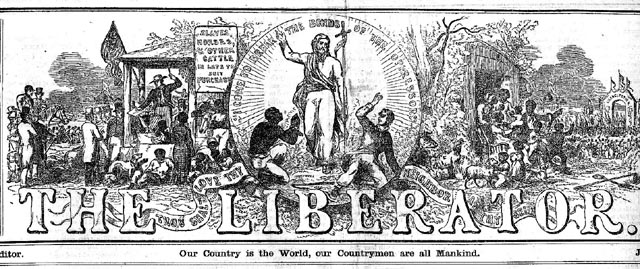

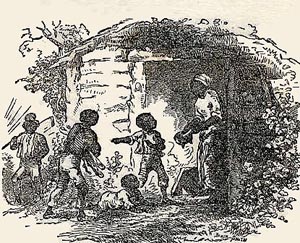

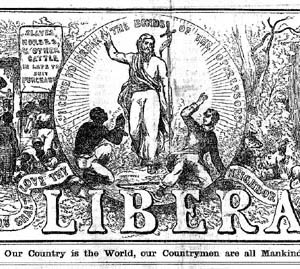

The title page vignette of Aunt Chloe in the cabin

doorway mirrors the cabin on the right side of the

Liberator design.

SOURCE

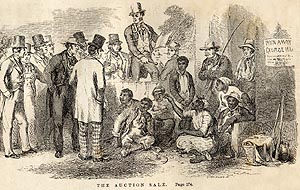

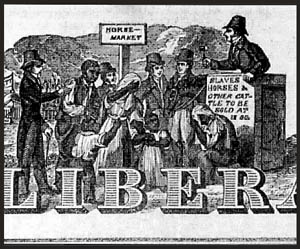

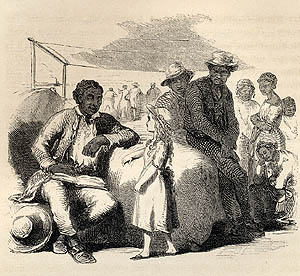

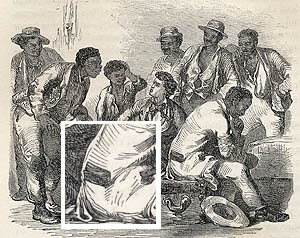

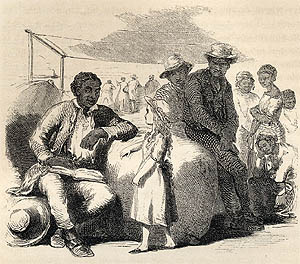

As well, his “The Auction Sale” resembles the scene on the left side of the banner print.

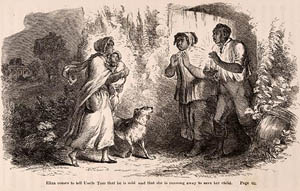

Both antislavery iconography and conventions of fine art likely inspired Billings’s conception of “Eliza comes to tell Uncle Tom that he is sold, and that she is running away to save her child.”

When The Liberator debuted in 1831 its masthead had borne the image of a mother and children at a slave market.

SOURCE

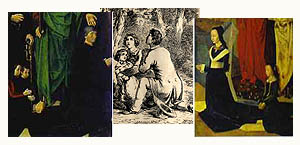

Billings’s mother, Eliza, cradles a child in her arms, and, like the slave on that first masthead, her head and shoulders are covered in the fashion of a Madonna as seen in European paintings from the Renaissance.

Her little boy, Harry, described as “a small quadroon boy, between four and five years of age,” here seems to be an infant — a babe in swaddling clothes perhaps?

SOURCE

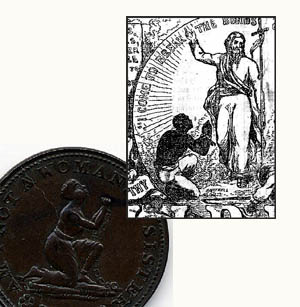

Probably the most long-lived icon of the antislavery movement was a kneeling figure, much like the slave Billings placed at the feet of Christ on his Liberator masthead.

An 1838 anti-slavery token circled by the plea, “Am I Not A Woman and a Sister,” is an example.

SOURCE

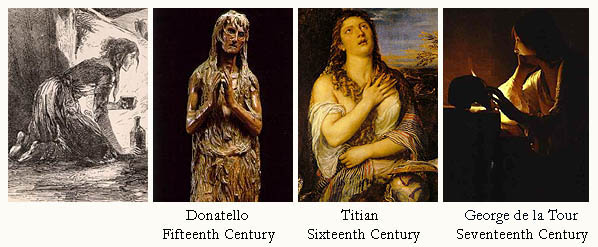

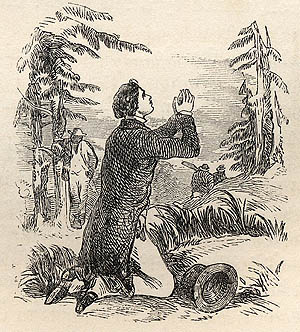

The kneeling posture was understood in the United States as a pose of Christian supplication in an artistic tradition that also traces back to European paintings from the Renaissance.

Donors who paid for a church altarpiece would have the artist portray them, in profile, kneeling in prayer on the side panels.

SOURCE

In “The fugitives are safe in a free land,” George and Eliza Harris, safely arrived in Canada, fall to their knees thanking God for their deliverance.

Harry is noticeably older here and wears a broad round hat that could suggest a halo.

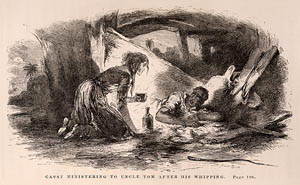

Two pictures for that original 1852 edition had no antislavery connections. A gun-toting escaping slave, such as in “The Freeman's Defence,” was not so inspiring as praying families to the middleclass women who comprised the antislavery movement’s target audience. And “Cassy ministering to Uncle Tom after his whipping,” the wild-haired slave woman, strong-willed and shrewd, not to mention sexually tainted, was not a type of femininity easy for women to reconcile.

Two pictures for that original 1852 edition had no antislavery connections. A gun-toting escaping slave, such as in “The Freeman's Defence,” was not so inspiring as praying families to the middleclass women who comprised the antislavery movement’s target audience. And “Cassy ministering to Uncle Tom after his whipping,” the wild-haired slave woman, strong-willed and shrewd, not to mention sexually tainted, was not a type of femininity easy for women to reconcile.

SOURCE SOURCE SOURCE

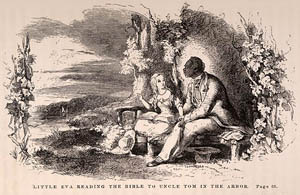

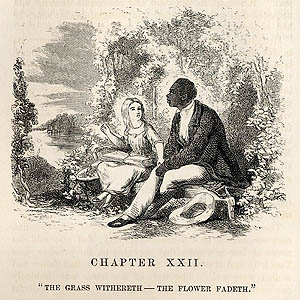

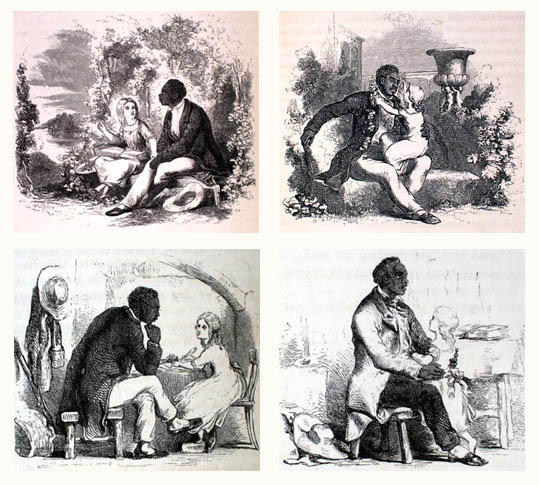

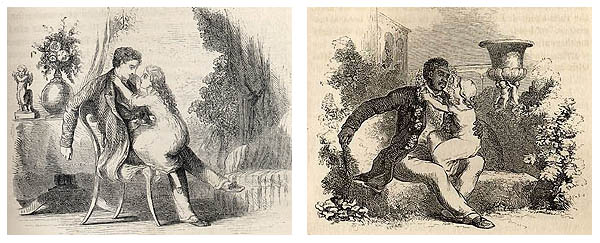

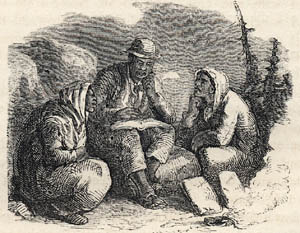

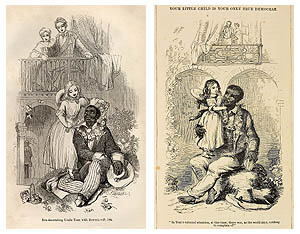

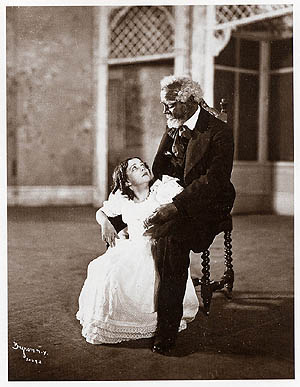

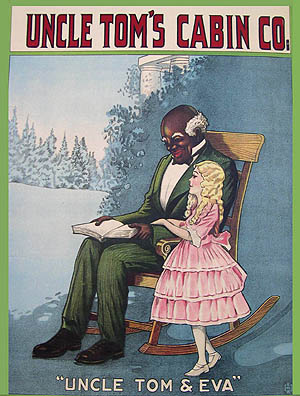

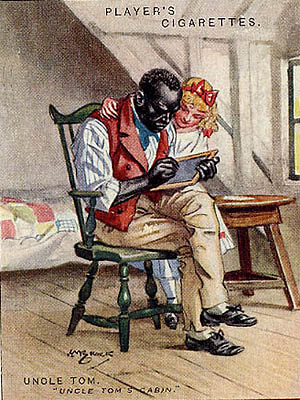

Among those initial six engravings, “Little Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the arbor” was, according to Billings’s biographer James F. O'Gorman, “without doubt the most important image of the first edition.”* Unlike the slave Madonna or praying supplicant, there was no visual precedent for a grown black man, in the prime of life, cozied up with a tiny white girl, alone, out in nature.

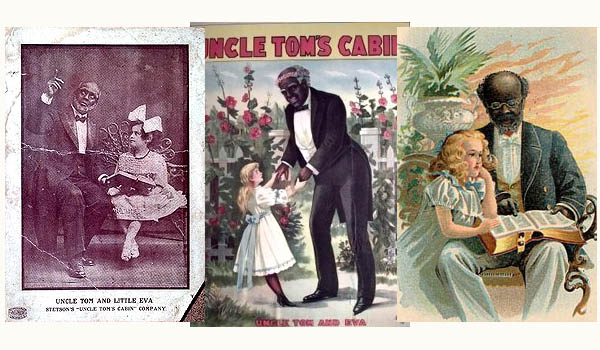

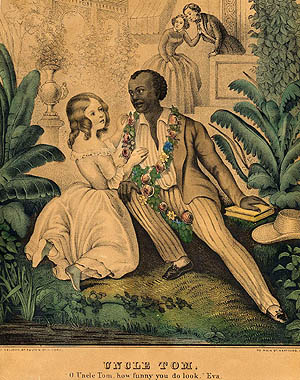

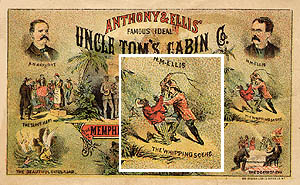

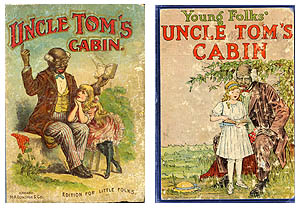

Viewed outside the context of the novel, Tom and Eva in the arbor would seem to have been a remarkable sight. Nonetheless, of all Billings’s scenes, this one most captivated viewers. Almost immediately it inspired a painting, songs, sheet music covers, several fine art prints, and all manner of ephemera. Forever after, if a book included illustrations, there among the pages would be Tom and Eva in a garden. Frequently they also graced the cover.

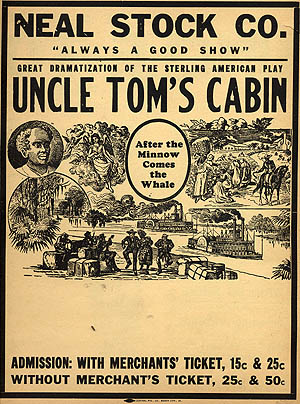

As theatrical performances of the story grew in popularity, commercial prints were created to promote these “Tom Shows.” Theaters were festooned with likenesses of Tom and Eva.* Actors playing Tom, actresses costumed as Eva sold photo cards of themselves. From scores of scenes in the story, generated for over 150 years, Tom and Eva together have been the most reproduced characters from the story.

SOURCE SOURCE SOURCE

For many readers, “Little Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the arbor” is a puzzling sight. Only the story could have prompted Billings to partner a slaveholder’s daughter with a slave, described by Stowe as “a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man.”* In studying this illustration, I have wondered if Billings’s odd couple became popular precisely because it was sexually charged, implicitly courting the unmentionable, then so unequivocally squelching any chance that the man of African descent could live out his masculine potential.* Most of Billings’s work was conventional, retracing antislavery icons or inspired by traditional art. The exception was of course his rendition of Tom and Eva, new to imagery. In practice, slaves were not allowed to read, and were sometimes punished for trying to learn. White men had the ordained privilege to speak the Christian word, not slaves with little girls.* The act of reading the Bible together was an undermining of patriarchal authority potentially more disruptive than even abolitionism.

For many readers, “Little Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the arbor” is a puzzling sight. Only the story could have prompted Billings to partner a slaveholder’s daughter with a slave, described by Stowe as “a large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man.”* In studying this illustration, I have wondered if Billings’s odd couple became popular precisely because it was sexually charged, implicitly courting the unmentionable, then so unequivocally squelching any chance that the man of African descent could live out his masculine potential.* Most of Billings’s work was conventional, retracing antislavery icons or inspired by traditional art. The exception was of course his rendition of Tom and Eva, new to imagery. In practice, slaves were not allowed to read, and were sometimes punished for trying to learn. White men had the ordained privilege to speak the Christian word, not slaves with little girls.* The act of reading the Bible together was an undermining of patriarchal authority potentially more disruptive than even abolitionism. With an unprecedented 300,000 copies of this original Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold, publisher Jewett contracted Billings to draught over 100 more engravings for a fancier version to be out in time for Christmas gift giving (but with publication date of 1853).* A look at the cuts Billings made for a second book that same year offers an opportunity to reconsider the significance of that strategically placed Bible on Eva’s lap. It seems intended to thwart a sexual reading — to deflect attention from Eva touching Tom’s leg — but perhaps their Bible study is even more subversive than their intimacy.

With an unprecedented 300,000 copies of this original Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold, publisher Jewett contracted Billings to draught over 100 more engravings for a fancier version to be out in time for Christmas gift giving (but with publication date of 1853).* A look at the cuts Billings made for a second book that same year offers an opportunity to reconsider the significance of that strategically placed Bible on Eva’s lap. It seems intended to thwart a sexual reading — to deflect attention from Eva touching Tom’s leg — but perhaps their Bible study is even more subversive than their intimacy.SOURCE

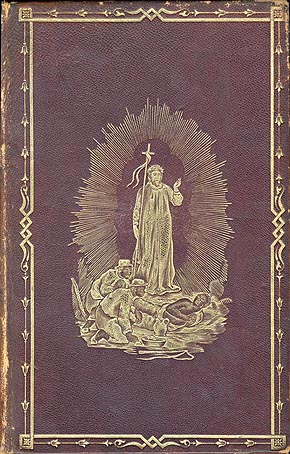

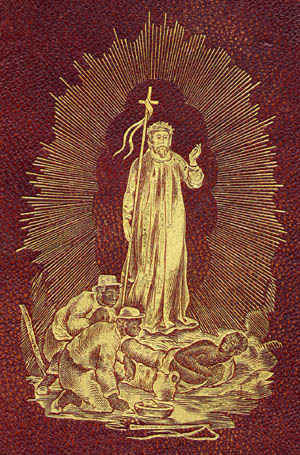

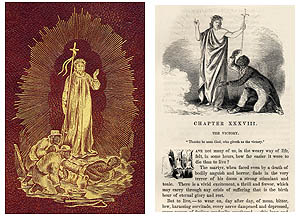

Billings’s design of this gift book even looked like a Bible. (Cover 1853) The front and back covers were dark red, with gold-embossed imprints of Christ.

SOURCE

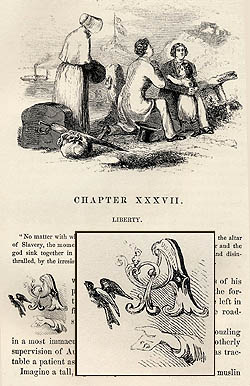

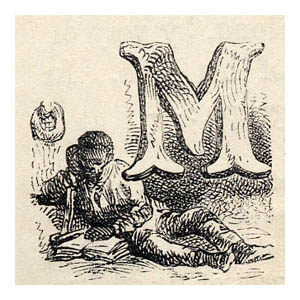

There were gilt-edged pages, and decorative letters topped each chapter.

Tiny imprints of angels, praying figures, and doves augmented the more narrative imagery.

The Bible held a special place in antebellum American homes.* Billings knew to place a Bible on the side table in Eliza’s humble room.

According to Colleen McDannell, “family Bibles were displayed on parlor tables as signs of domestic piety and taste.”* Beginning with Isaiah Thomas’s illustrated English Bible of 1791, Bibles in America were picture books with stamped decoration or embossing.

This larger format, gold-embossed, amply illustrated version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin resembled the Bible it soon joined on many a parlor table.

For the gift book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Billings interpreted Stowe’s story in three, distinctly Christian, visual narratives. In the first part of the book Tom is an itinerant minister. The text tells of prayer meetings he held on the Shelby plantation before he was sold down the river.

A chapter letter shows him reading a bible.

Traveling on the boat with others to the New Orleans market, he clutches a Bible as he consoles a weeping slave woman.

A large Bible is open on his lap when he first encounters little Eva St. Clare out on the deck . . .

. . . and the Bible is still in his hands when she brings her father to meet him.

This section of the story culminates in a scene Elizabeth Ammons calls a “figurative baptism [which] signifies their oneness in Christ.”* Tom had jumped overboard to save Eva from the river, now arms reach down to pull them back on board, a halo of helping hands.*

In a second visual testimony of his faith, Tom assumes a active Christian persona. Upon her insistence, Eva’s father, Augustine St. Clare, purchased Tom and he became her constant companion and confidant.

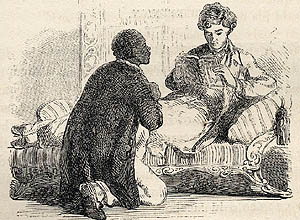

While on the St. Clare plantation Tom assumes the role of an intercessor in the posture of supplicant . . .

. . . on his knees praying for the conversion of St. Clare . . .

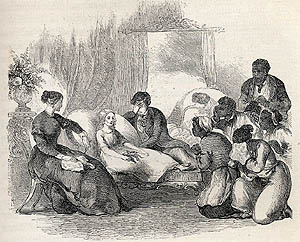

. . . praying for Eva to regain her health . . .

. . . mourning Eva as she grows weaker . . .

. . . and mourning St. Clare, dying from an untimely wound.

Scenes of Tom and Eva together emphasize Stowe’s challenge to the patriarchal order.

Eva snuggling onto her father’s lap varies little from her cozy times with Tom.

Fathers were purveyors of Bible wisdom, the “Lord and master” in the home who delivered the word.

St. Clare neglected his patriarchal duty to inculcate Christian doctrine, leaving that to Tom.

Through his devout professions, his council, Tom fulfilled a father’s role. It was with Tom that Eva grew in her Christian commitment.

Eva died, St. Clare was killed, and once again Tom became an itinerant preacher.

In the slave warehouse as he awaited being sold again, a Bible protrudes from his coat pocket.

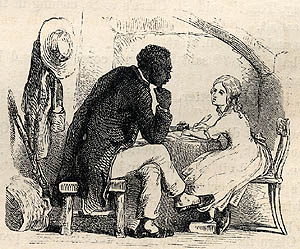

He ministers to slave women.

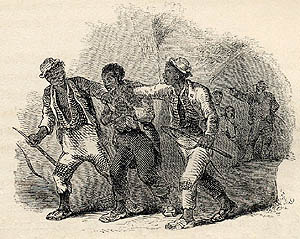

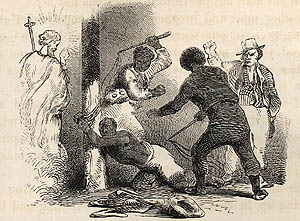

During Billings’s final third of the novel Tom reenacts the passion of Christ. For not renouncing his beliefs to bow down to his earthly “master,” Simon Legree orders Tom whipped (as if “condemned by Pontius Pilate”).

Tom is led off, down his own “road to Calvary.”

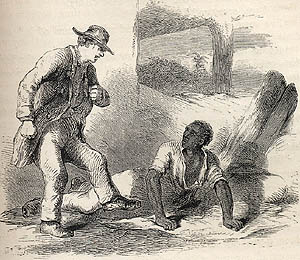

Knocked down by Legree . . .

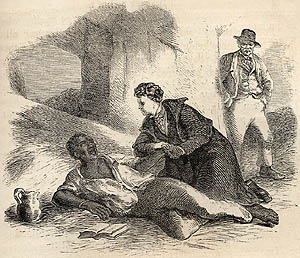

. . . later he is comforted, given drink by Cassy the Magdalene.

He is tortured repeatedly at Legree’s command.

A “crucifixion” ensues with Tom lashed to a post, and beaten, while a vision of Christ sustains him.

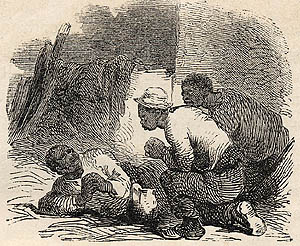

As Tom dies, Sambo and Quimbo, slaves he had converted, grieve (in “lamentation”).

George Shelby, son of the slaveholder who first sold Tom, arrives too late . . .

. . . but sees to his burial (his “entombment”).

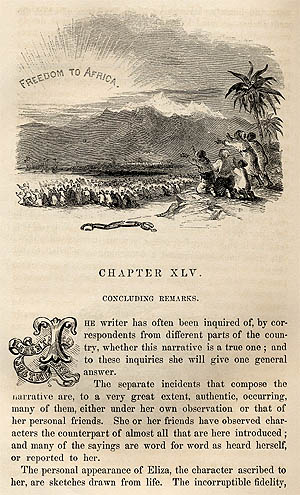

The novel ends in “resurrection,” with multitudes of freed people in exodus toward a radiant sky blazoned “Freedom to Africa.”

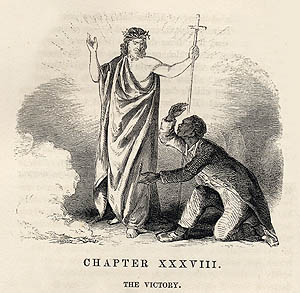

In a final chapter called “The Victory” Christ stands triumphant as Tom kneels in obeissance, another reprise of the Liberator design.

With the gold-embossed figure of Christ on the cover and picture stories of Tom reenacting a passion play, Billings’s 1853 Uncle Tom’s Cabin didn’t just look like a Bible, it was a veritable New Testament.

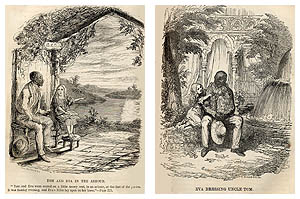

“Tom and Eva in the Arbour,” and “Eva Dressing Uncle Tom,” were among 27 whole page, wood engravings that the renowned English artist George Cruikshank created for one among 14 different publications issued in Great Britain in 1852, with four to follow in 1853. Cruikshank’s “Tom and Eva in the arbour” shows the influence of Billings by being similarly positioned but in reverse. Manicured gardens add a distinctly English touch. SOURCE

“Tom and Eva in the Arbour,” and “Eva Dressing Uncle Tom,” were among 27 whole page, wood engravings that the renowned English artist George Cruikshank created for one among 14 different publications issued in Great Britain in 1852, with four to follow in 1853. Cruikshank’s “Tom and Eva in the arbour” shows the influence of Billings by being similarly positioned but in reverse. Manicured gardens add a distinctly English touch. SOURCE

“Uncle-Tom-mania” was unquenchable, as entrepreneurs rushed out more illustrated editions, Tom almanacks, songbooks, wallpaper, and notepaper with scenes from the book. Tom and Eva were immortalized as fine porcelain figurines. The English even coined a word — “Tomitudes” — to describe their penchant for the slave.* As testament to Uncle Tom’s impact on Britons, the British Museum today owns an extensive collection of "Tomiana."*

SOURCE

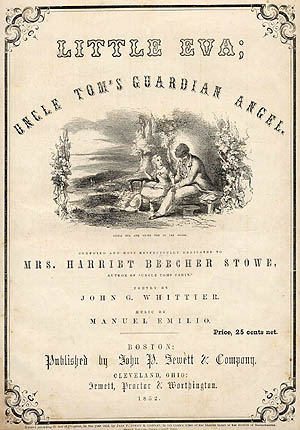

If popularity can be measured by the number of imitators, Billings’s illustration of Tom and Eva was an immediate success. His own engraving became the cover of a song, Little Eva: Uncle Tom's Guardian Angel, with words by John Greenleaf Whittier.

SOURCE

It was copied as an oil painting by African-American artist Robert Scott Duncanson for a commission from James Francis Conover, editor of The Detroit Tribune.*

SOURCE

In an engraving by F. L. Jones from a painting by A. Hunt Tom fit Stowe’s description of a “large, broad-chested, powerfully-made man” of a “full glossy black” color.

SOURCE

On a lithographic sheet music cover published in London, artist J. Brandard emphasized Tom’s athletic physique and Eva’s delicacy. Sitting close to Tom, Eva gently grasps his proffered arm as she casts their joined gaze into the distance.

SOURCE

Another lithograph, published by E. C. Kellog, meant to be framed and mounted as home décor, also found Tom looking robust.

SOURCE

An illustration in The New York Family Story Paper in 1873 for Adah M. Howard’s short story, “Uncle Ned's Cabin, or, the Little Angel Comforter,” was a barely disguised updating of Stowe’s story and Billings’s arbor scene. “Ida,” sitting with grey-haired, slumped old Uncle Ned, points toward "the Heavenly Zion" just as Eva once had.

SOURCE

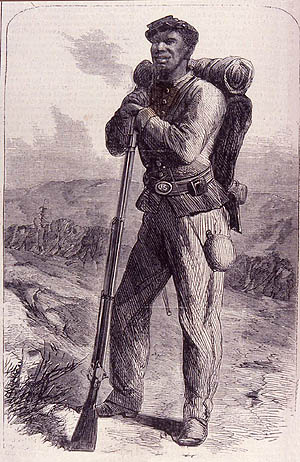

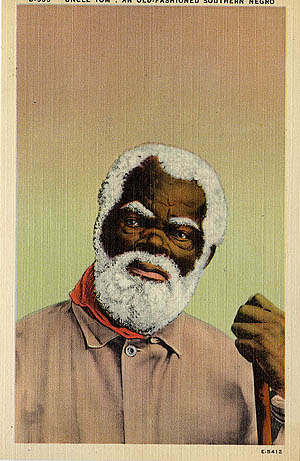

A rapid aging of black men occurred throughout visual culture.

In his dark blue uniform, standing tall, “Union Jim” had been inspiring propaganda to justify the Civil War for northern readers of Harper's Weekly. Once his battle service was over, and he was free, there were no more such prints of young men, only elderly former slaves who spoke well of “old massa” and held fond memories of slavery.

SOURCE

An engraving by Richard Norris Brooke for the front page of Harper's Weekly in the early 1870s is an example.

SOURCE

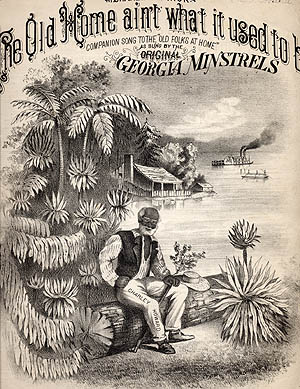

Covers on songs of the 1870s featured a profusion of old “uncles” with tufts of grey hair and stooped over postures returning South to find “The Old Home Aint What it Used To Be.”

SOURCE

Sterling Brown termed the literary type a “wretched freedman, a fish out of water," as an example of how “stereotypes . . . have evolved at the dictates of social policy.”* There was no place in American life for the strong figure of an adult, male African-American head of household. Unable to thrive without slavery it was implied, the wretched freedman yearned for a return of the old ways. North and South joined forces, developed an agricultural peonage system — sharecropping — kept in place by a complex web of political, social, economic limitations, and eventually aided by “Jim Crow” laws. Visual culture responded with images of an idyllic South where the “old folks” remained at home. In the ultimate irony, African-American characters such as Tom became loyal slaves in perpetuity.

SOURCE

By continually restaging Uncle Tom’s life, artists, actors, producers, found a way to keep slavery viable as an ideology of race and class that helped assuage regret over the “Lost Cause” by championing a belief that the old regime was better.

SOURCE

Minstrel performances became a “comforting facade of romanticized, folksy caricatures.” Cast aside were “wiley tricksters and antislavery protesters,” from pre-emancipation days, “for loyal, grinning darkies.”* Or, Toll might have added, old uncles.

Minstrel performances became a “comforting facade of romanticized, folksy caricatures.” Cast aside were “wiley tricksters and antislavery protesters,” from pre-emancipation days, “for loyal, grinning darkies.”* Or, Toll might have added, old uncles.Tom the father, husband, strong fieldworker was gone.

SOURCE

He had died his martyr’s death at the end of the novel.

Appropriately, Tom the venerable, grandfatherly companion of Eva was the figure that lingered in the imagination. Not a dark ghost of slavery past, but a beloved slave who never was, and so could always be.

SOURCE

Uncle Tom and his story thrived into the twentieth century. More books were published with illustrations showing Eva in up to date fashions.

SOURCE

A few Tom Shows were still touring in the 1940s, and played on occasion into and beyond the 1950s.

SOURCE

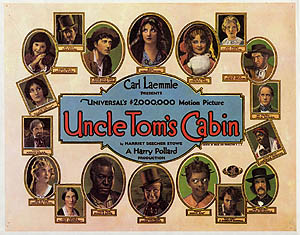

There were several motion pictures, beginning in 1903 with a fifteen-minute film directed by Edwin S. Porter.

Carl Laemmle produced a big budget, well-publicized, full-length feature in 1927, and as recently as 1989 Avery Brooks starred as Tom in a film.

SOURCE

Shirley Temple and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson made several films in which they replayed the Tom and Eva dynamic. In The Little Colonel and The Littlest Rebel, both of 1935, Temple was a precocious young Belle.

SOURCE

Robinson was her “servant” pal, “Uncle Billy.”*

SOURCE

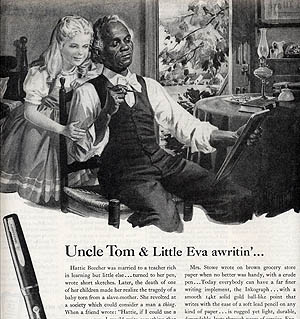

In both the United States and Europe, advertising prints featured Tom and Eva.

SOURCE

In an 1946 magazine ad for the Ink-O-Graph pen, as Tom pulled back to survey his handiwork, Eva stood behind him, her right hand proprietarily on his arm. Despite the fact that Tom brandished a fine writing implement, he had made his marks on a child’s toy blackboard. Uncle Tom had been “awritin’” boasted the ad.

As for Tom the Christian — never again was he accorded such respect as in illustrations by Hammatt Billings for Stowe’s gift book of 1853. Tom the minister, prayerful intercessor, Christ-like martyr disappeared from sight.

SOURCE

In 1938, the Mexican modernist Miguel Covarrubias created lithographic prints for a collector’s edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His Tom prayed with arms raised, in a ritual of movement, suggesting African roots, emotional, not reasoning and literate as the original Tom had been.

SOURCE

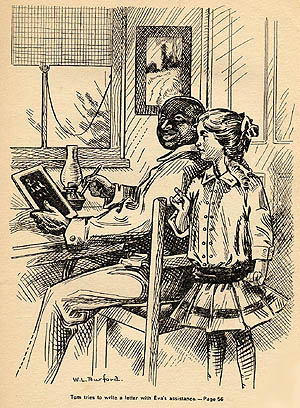

Even Tom’s Bible was taken away. “Tom tries to write a letter with Eva’s assistance,” read a caption of an illustration by W. L. Burford from around 1900.

SOURCE

Whatever challenge this pathetic old man once posed to the white male patriarch as fatherly figure and purveyor of the Christian word faded from memory quicker than chalk dust blown from a felt eraser.

SOURCE

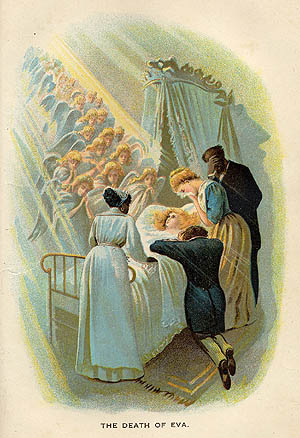

As might be expected, the only character in the novel to retain piety was little Eva. White, blond, evanescent, bathed in lights, she had dominated stage shows as an angel being welcomed into heaven in a glorious apotheosis.

This 1900s book illustration was also used on Tom Show posters.*

SOURCE

Evangeline forever, an alabaster seraph, rising to glory as curtains fell.

Hammatt Billings depicted Harriet Beecher Stowe’s title character as the strong worker, self-sacrificing father, head-of-household, and devout Christian that he was. His images give us insight into the Uncle Tom whom Stowe intended to bring to life. Abolitionist novel? Perhaps. Evangelical Christian tract? Most definitely.

What happened to Tom in the hands of others tells us just how revolutionary a story Uncle Tom’s Cabin truly was, and why so much effort was put forth over the years to contain that radical potential.