| Few people would disagree with the statement that Uncle Tom's Cabin has been both a progressive and a reactionary force in American culture. The problem is accounting for how one text can have such a varied political text. Or, perhaps that is the wrong question. What if Uncle Tom's Cabin is thought of as many texts? That is to say, what if we think of Uncle Tom's Cabin not just as a novel created by an author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, but as a text created and recreated by readers, adapters, and even those politically hostile to Stowe? |

|

Then there would be an obligation to consider those texts that responded to or made use of Uncle Tom's Cabin as in themselves significant. Too often these texts (other novels, plays, poems, songs, advertisements, newspaper reports, letters to the editor, etc.) are only given attention as a reflection of the popularity or impact of Stowe's novel. But they can also be viewed as the very means by which Uncle Tom's Cabin assumed importance in American culture, as what began as Stowe's novel was taken up by others and interpreted, reconsidered, and, to use the term central to this argument, articulated. The character of Topsy, as she was constructed by Stowe and subsequently reconstructed by others, illustrates how disparate cultural elements can take on a range of political and social meanings. |

| Stuart Hall's definition of articulation provides the

most helpful guide to this approach. As a concept, articulation has a much more

obvious connotation in England because of the popular term "articulated

lorry," which refers to what in the U. S. is called a "tractor trailer

truck." Articulation in this sense refers to the manner in which the

trailer section can be detached and hooked up with different tractor sections.

Despite the non-necessary correspondence between these two parts, the

combination would be referred to as a truck. However, "truck," from

this perspective, needs to be seen as the articulation of two separate elements

into a unified construct.

Articulation has been defined more formally by Hall as: the form of the connection that can make a unity of two different elements, under certain conditions. It is a linkage which is not necessary, determined, absolute and essential for all time. You have to ask, under what circumstances can a connection be forged or made?*Articulation describes the means by which cultural elements can be joined together as well as the contingent nature of those linkages. Hall insists that there is nothing essential in these cultural combinations (just as a trailer section can be moved onto any truck), but that under certain conditions specific combinations are most likely and have something to tell us about the nature of those conditions. In short, material conditions matter, even if they do not "determine" in the traditional sense. Following Raymond Williams, Hall has insisted that "[m]aterial circumstances are the net of constraints, the conditions of existence' for practical thought and calculation about society"* The important work to be done by theorizing lies not in predicting outcomes, but in establishing what action to take (or what action could have been taken) given a set of circumstances. |

The advantage of the concept of articulation in the context of

Uncle Tom's Cabin is that it allows an examination of Stowe's novel

as part of a cultural pattern, not as an isolated creative act. Stowe's novel

put into combination a series of cultural elements (including religion, slavery,

melodrama, and family crises), but those elements then became available for

reinterpretation and re-articulation, as becomes apparent in an examination of

the long, varied history of representations of one of Stowe's most popular

characters, Topsy. The advantage of the concept of articulation in the context of

Uncle Tom's Cabin is that it allows an examination of Stowe's novel

as part of a cultural pattern, not as an isolated creative act. Stowe's novel

put into combination a series of cultural elements (including religion, slavery,

melodrama, and family crises), but those elements then became available for

reinterpretation and re-articulation, as becomes apparent in an examination of

the long, varied history of representations of one of Stowe's most popular

characters, Topsy. |

It would be wrong to consider Stowe's Topsy as the

"authentic" creation that was simply degraded by those making use of

her after Stowe. The character of Topsy began as a combination of different

cultural elements. Within Stowe's Topsy can be found elements of minstrel

stereotypes, the trope of the "wild child," and anxiety about the

working-class. When St. Clare first introduces Topsy he says, "I thought

she was rather a funny specimen in the Jim Crow line" and tells her to

"give us a song, now, and show us some of your dancing."*

Topsy's

routine, consisting of spins, claps, odd singing and a concluding somersault,

was to be substantially enhanced in subsequent theatrical performances. However,

the minstrel element already in the Topsy of the novel was there for later

adapters to re-articulate, in this case back into the tradition from which she

had partially "grow'd." It would be wrong to consider Stowe's Topsy as the

"authentic" creation that was simply degraded by those making use of

her after Stowe. The character of Topsy began as a combination of different

cultural elements. Within Stowe's Topsy can be found elements of minstrel

stereotypes, the trope of the "wild child," and anxiety about the

working-class. When St. Clare first introduces Topsy he says, "I thought

she was rather a funny specimen in the Jim Crow line" and tells her to

"give us a song, now, and show us some of your dancing."*

Topsy's

routine, consisting of spins, claps, odd singing and a concluding somersault,

was to be substantially enhanced in subsequent theatrical performances. However,

the minstrel element already in the Topsy of the novel was there for later

adapters to re-articulate, in this case back into the tradition from which she

had partially "grow'd."The wild child, separated from her mother and mistreated, was a familiar trope in sentimental fiction. In fact, Stowe's solution for the problem of a wild child, the love of a substitute mother, was by no means unusual.* What was unique was Stowe's conflation of the wild child with the slave child. This act of articulation made a specific political use of the wild child trope by literally making slavery responsible for an ongoing concern of white, middle-class America, the motherless child in an economically uncertain world. As Christine Stansell has shown, shifts in employment practices as well as population increases in the 1850s led to a growth in the phenomenon of children separated from their parents and often on their own on the streets. "[L]arge numbers of children, who two decades earlier would have worked under close supervision as apprentices or servants, spent their days away from adult discipline."* Stowe's Topsy made a particular kind of sense under these conditions. In fact, Stowe was to later argue in A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin that the "problem" of Topsy was not specific to slavery. In the Key, she refers to the English working class and New York City prostitutes for whom educational and reform efforts were designed to "encourage self-respect, and hope, and sense of character."* Such methods are seen to apply to these populations in the same way they were to be applied to children like Topsy. By placing Topsy's condition alongside these cases, Stowe tapped into her readership's already existing concerns and available cultural narratives (including stereotypes), and then directed them all toward slavery. |

If Stowe's creation of Topsy involved a combination of

cultural elements with a governing narrative, then what is fascinating about

Topsy in the novel is that her character's development illustrates this very

process. Topsy appears mid-way through Stowe's novel when St. Clare buys the

slave child in order to put Miss Ophelia's educational and anti-slavery

theories to a practical test. He intentionally picks the physically battered and

seemingly incorrigible Topsy because he feels Ophelia's methods will not work

on a brutalized child of slavery, "one child, who is a specimen of

thousands among us."*

St. Clare is proven correct as Ophelia's methods

prove incapable of training Topsy, whose stealing, lying, and general demeanor

disrupt life in the St. Clare household. In fact, Ophelia's own antipathy

toward blacks stands in the way of changing Topsy's behavior. Only Eva's

genuine love and affection are able to have an effect on Topsy. Once convinced

that Eva cares for her, Topsy begins to change her ways, and Eva's death

causes her to strive to be good, "a strife irregular, interrupted,

suspended oft, but yet renewed again."*

If Stowe's creation of Topsy involved a combination of

cultural elements with a governing narrative, then what is fascinating about

Topsy in the novel is that her character's development illustrates this very

process. Topsy appears mid-way through Stowe's novel when St. Clare buys the

slave child in order to put Miss Ophelia's educational and anti-slavery

theories to a practical test. He intentionally picks the physically battered and

seemingly incorrigible Topsy because he feels Ophelia's methods will not work

on a brutalized child of slavery, "one child, who is a specimen of

thousands among us."*

St. Clare is proven correct as Ophelia's methods

prove incapable of training Topsy, whose stealing, lying, and general demeanor

disrupt life in the St. Clare household. In fact, Ophelia's own antipathy

toward blacks stands in the way of changing Topsy's behavior. Only Eva's

genuine love and affection are able to have an effect on Topsy. Once convinced

that Eva cares for her, Topsy begins to change her ways, and Eva's death

causes her to strive to be good, "a strife irregular, interrupted,

suspended oft, but yet renewed again."*In Stowe's account, what is most intriguing about Topsy is that she is a character without a personal narrative. As Ophelia's initial questioning of her reveals, Topsy knows nothing of her age, her parents, conceptions of time, or God. When asked by Ophelia if she knows who made her, Topsy replies "I spect I grow'd. Don't think nobody never made me."* It is partly this lack of a personal narrative that explains Topsy's function within slavery as a commodity. Without connections to anyone or any place, Topsy herself seems to care little whose possession she is. Topsy's situation provides a telling comparison with that of Uncle Tom. Uncle Tom's tragedy is that he does have a personal narrative, a family, and a past he is forced to leave, and as such he can appreciate personally the ramifications of being a slave. Topsy's initial tragedy is that she has no basis from which to oppose her situation. She cannot envision any alternative to her commodified existence within slavery.*

Following Eva's death, Topsy is once again accused of stealing. However, when confronted, it turns out she is hiding a book of Eva's given to her as a gift, one of Eva's curls and a strip of black crape leftover from Eva's funeral. When Topsy fears these items are to be taken from her, she pleads with Ophelia to let her keep them. In their relation to Eva, these almost fetishized elements are linked to the change in Topsy's behavior. "Topsy did not become at once a saint; but the life and death of Eva did work a marked change in her."* The objects become the building blocks, for Topsy, of the personalized narrative whose absence so acutely marked her pre-conversion state. The change in Topsy serves to illustrate the difference between an arbitrary collection of cultural elements and a collection informed by a governing narrative. It is, for Stowe, as if Eva's intervention moves Topsy from caricature to character. |

| Articulation is by definition a contingent act. Elements

brought together in the character of Topsy could be re-articulated in different

situations. In fact, the history of the Topsy figure illustrates what could be

called "the return of the articulated." Topsy's character as written

by Stowe was both to be laughed at and sympathized with, befitting a creation

that drew on both the minstrel and the sentimental tradition. But as Topsy

became part of popular culture, particularly in stage versions of Uncle Tom's

Cabin, the minstrel aspect of her character came to define her more than the

sentimental aspect. In this case, as laughter replaced tears,

representations of Topsy began to do quite different cultural work.

In Stowe's novel, Ophelia convinces St. Clare to sign over ownership of Topsy to her, so she can take her to Vermont and free her. Topsy leaves the novel once the story proceeds down river to Simon Legree's plantation. In contrast, Aiken continues the story in Vermont with the addition of the character of Cumption Cute, a distant relative of Ophelia's who attempts to swindle her out of money. When Cute arrives at Ophelia and Topsy's Vermont home, his initial exchange with Topsy provides the ugliest comedic racism in the play as he refers to Topsy by a number of epithets and suggests exhibiting her as a Barnumesque curiosity. Topsy, though she doesn't entirely understand Cute's offer, refuses to leave. Her decision is supported by Ophelia who tells Topsy, "you know you are very comfortable here--you wouldn't fare quite so well if you went away among strangers."* Eventually, Cute is driven out of their house by Ophelia, accompanied by a broom-wielding Topsy in a bit of slapstick humor which would not be unfamiliar in a minstrel show.

|

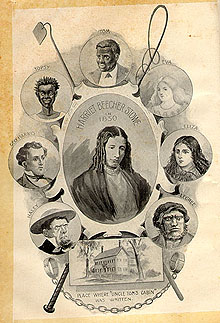

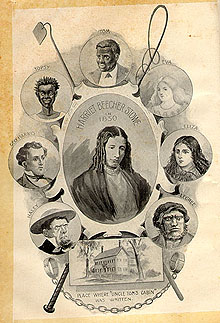

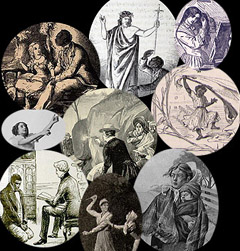

These contrasting portrayals of Topsy can also be seen in two

visual representations. The first comes from an advertisement in Frederick

Douglass' Paper for a poem entitled "Topsey, [sic] or, the Slave Girl's

Appeal" (see left). In this picture, Topsy stands in a demure,

straight-backed pose with her hair neatly combed, her toes pointed and her hands

folded in front of her. Her dress, though not as refined as Eva's, is not out

of keeping with middle-class, nineteenth-century fashion. These contrasting portrayals of Topsy can also be seen in two

visual representations. The first comes from an advertisement in Frederick

Douglass' Paper for a poem entitled "Topsey, [sic] or, the Slave Girl's

Appeal" (see left). In this picture, Topsy stands in a demure,

straight-backed pose with her hair neatly combed, her toes pointed and her hands

folded in front of her. Her dress, though not as refined as Eva's, is not out

of keeping with middle-class, nineteenth-century fashion.

The first image, though it displays an obvious sympathy for Topsy, also suggests models of behavior and physical beauty for Topsy based on white, middle-class ideals. In fact, the ability of Topsy to achieve those ideals appears to be at the heart of the "slave girl's appeal." Eva's hectoring gesture with her finger is one sign of the disciplining procedure by which it is understood that Topsy could be brought into conformity with white, middle-class standards. As troubling as that figure may be, the second Topsy is more problematic. It suggests that the dominant image of Topsy is not, as in the prior figure, that of a child who can be reformed, but rather of an incorrigible imp. Topsy's wildness, as this picture illustrates, made her a popular part of the plays. According to Harry Birdoff, Topsy was the big draw when touring companies went through the west after the Civil War. As performances of the play developed, additional songs were written for Topsy. "I'se So Wicked" had been her signature tune as early as the Aiken plays, but as music came to play a larger role in performances, Topsy began singing additional songs such as "Bekase My Name Am Topsey [sic]."

|

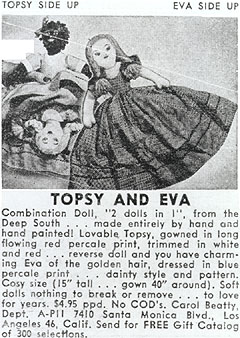

The most lasting image of Topsy, however, is in her contrast

to Eva. While the image of the advertisement from Frederick Douglass' Paper

emphasized continuities between Eva and Topsy, the image of Topsy which came to

dominate placed her in direct contrast to Eva. While Eva was portrayed typically

as refined, demure and very white, Topsy was represented as crude, immodest and

very black. This binary opposition was literalized when the popular Topsy-Turvy

doll (which pre-dated Uncle Tom's Cabin) was made into the Topsy/Eva

doll (Figure 11a). This doll could be either character -- "Lovable Topsy"

or "charming Eva" according to the advertisement copy-- depending on

which side of their shared dress was flipped up, but the advertisement itself

illustrates the unevenness of this "sharing." In the photograph of the

doll, Eva is at the center. Her eyes face the viewer and her "dainty"

blue dress takes up much of the right side of the photo. Topsy is pushed off

into the upper left hand corner. Her eyes look off into the distance and her

dress is folded up so as to show the head of Eva. Shirley Samuels and Karen

Sanchez-Eppler have written about this doll as both illustrative of the

representation of racial differences under segregation and suggestive as to the

instability of those differences.*

However, as a lasting image, what is

significant is that the relationship between the white Eva and the black Topsy

structured representations of white and black girls into the twentieth century.

The most lasting image of Topsy, however, is in her contrast

to Eva. While the image of the advertisement from Frederick Douglass' Paper

emphasized continuities between Eva and Topsy, the image of Topsy which came to

dominate placed her in direct contrast to Eva. While Eva was portrayed typically

as refined, demure and very white, Topsy was represented as crude, immodest and

very black. This binary opposition was literalized when the popular Topsy-Turvy

doll (which pre-dated Uncle Tom's Cabin) was made into the Topsy/Eva

doll (Figure 11a). This doll could be either character -- "Lovable Topsy"

or "charming Eva" according to the advertisement copy-- depending on

which side of their shared dress was flipped up, but the advertisement itself

illustrates the unevenness of this "sharing." In the photograph of the

doll, Eva is at the center. Her eyes face the viewer and her "dainty"

blue dress takes up much of the right side of the photo. Topsy is pushed off

into the upper left hand corner. Her eyes look off into the distance and her

dress is folded up so as to show the head of Eva. Shirley Samuels and Karen

Sanchez-Eppler have written about this doll as both illustrative of the

representation of racial differences under segregation and suggestive as to the

instability of those differences.*

However, as a lasting image, what is

significant is that the relationship between the white Eva and the black Topsy

structured representations of white and black girls into the twentieth century.Most significantly, Shirley Temple's screen persona drew greatly upon the culturally available images of the precocious Eva. This debt was acknowledged directly in Dimples (1936), in which Temple played a child actress who starred as Eva in the first production of Uncle Tom's Cabin. |

[CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN VIDEO FORMAT] |

An even more pertinent Temple movie

was The Littlest Rebel (1935), a film set in the antebellum South.*

In one scene, Temple is presented with a gift by a young black girl who dressed in

the typically ragged clothes of a Topsy figure. When the young girl begins to

make a speech to Temple, the girl becomes flustered and starts to cry. Temple

consoles her and thanks her for her generosity. The kindness and assurance of

Temple is contrasted to the awkwardness and insecurity of the young black girl.

The dynamic of Eva and Topsy is replayed, only now the relationship between the

angelic while girl and the unrefined black girl has been universalized.

|

Within this context, a scene in Toni Morrison's The

Bluest Eye (1970) takes on particular relevance. Claudia, Morrison's

protagonist, is an adolescent African American girl with a fierce hatred of

Shirley Temple. While Claudia's sister and their friend find Temple cute,

Claudia despises her and can only think of the actress in the context of a

Shirley Temple doll she had been given as a gift. Claudia has no love for this

doll, though she is curious as to why this particular representation is so

universally admired. Her curiosity leads her to dismember the doll.To see of what it was made, to discover the dearness, to find the beauty, the desirability that had escaped me, but apparently only me. Adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs--all the world had agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured.*Of course, the dismemberment of the doll--Claudia explores and then destroys its face, hair and features--is an act of violence as well as curiosity. In the ideals of the Shirley Temple doll, Claudia finds societal standards that only make her feel worse about herself and make her hate white girls. Psychologically, the Shirley Temple doll still shares a dress with Topsy. The doll's beauty and grace implicitly is contrasted with the ugliness and awkwardness that Claudia is made to feel about herself.

|

| FIGURE CREDITS: 1. William McDonald; 3, 4 & 6. Clifton Waller Barrett Collection, Univ. of Virginia; 5. Univ. of Wisconsin Library, Rock County Campus; 6a, 10 & 11a. Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford; 7. Special Collections Dept., Univ. of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City; 9. Special Collections, Univ. of Virginia: Purchased with funds from the Robert and Virginia Tunstall Trust; 12. © 1935 Twentieth Century-Fox; 13. John Hay Library, Brown Univ. |