In 1918, the hospital doctors, nurses, and staff of the American Expeditionary Force Base hospital at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse, France, celebrated the Fourth of July with a parade of floats featuring American icons, such as Lady Liberty, the Stars and Stripes, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.* Moving past the ironies involved in the appearance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a symbol of the United States, which was fighting supposedly to make the world safe for democracy, the parade organizers’ choice of the cabin makes sense when we look at the lessons implicit in the decorative arts and material culture inspired by the novel. First, Tom-themed material culture and decorative arts demonstrate how commercial commodities give visual representation in domestic and leisure life to values derived from literature. Second, the preference of audiences for Tom-themed entertainment testifies to the strong, enduring transatlantic appeal of the play and its identification with the core values of the United States. Third, the popular stage shows derived from the novel and the decorative arts that both novel and plays inspired indicate how Harriet Beecher Stowe artfully drew on popular culture. This immersion helped to make the novel a bestseller and it, in turn, catalyzed the manufacture of popular culture commodities that extended the influence of the novel because of their ubiquity and popularity. By the early twentieth century, the role of transmitting messages about interracial harmony had shifted to the Tom shows from their progenitor — the novel. As an aside to the main points of this article, readers may want to know that the material culture and decorative arts inspired by Uncle Tom’s Cabin offer many ironies when we compare the free labor lauded in the novel with the manufacturing processes that produced them. For example, child labor helped to produce the earthenware figures and transferware pieces displayed in the section labeled Tomitudes on the Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture (hereafter UTCAC ) website and their manufacture brought laborers’ into frequent, close contact with highly polluted air and toxic substances.*

When we consider the material culture of literature, that is products inspired and produced because of literary inspiration, we might call them tie-ins, in present-day marketing parlance. Before the second decade of the twentieth-century, tie-ins of literary works were unlicensed. A manufacturer did not have to obtain from the copyright holder permission to produce commodities based on the copyrighted work. Copyright holders frequently produced tie-ins in the form of books. The gift editions, paperback edition, and illustrated edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that John Jewett produced may be thought of as tie-ins. Jewett’s merchandising efforts with the novel shows how he and other publishers tried to fill every niche of the book market. In the publishing and literary world of the late eighteenth-century through the beginning of the twentieth century, publishers and authors rarely produced non-literary tie-ins such as mementoes, statues, needlework, and items of clothing. Nevertheless, publishers including Jewett realized the potential of non-literary tie-ins. For example, he paid John Greenleaf Whittier fifty dollars to write a poem about Little Eva, which he had set to music (above right).* In addition, an inexpensive handkerchief illustrated with the image from the sheet music of the Little Eva song probably helped to promote the popularity of both the novel and the song (below right). Neither Stowe nor her publisher, nonetheless, benefited from the proliferation in Europe and the United States of Uncle Tom’s Cabin products such as card games and puzzles, transferware food service vessels, porcelain and earthenware figures, and needlework.

For European and American manufacturers of commercial items purchased with discretionary income, the appearance of a literary bestseller such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin offered a bonanza. Because existing law did not deem that the characters, objects, and images associated with a text belonged to the author or copyright holder, anyone or any business might appropriate such a popular object and reproduce it for profit.* Despite Uncle Tom’s Cabin and other popular novels, such as those by Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, inspiring a multitude of tie-ins, nineteenth-century industrial, transportation, and business changes came into being after the rise of tie-ins and merely promoted their proliferation. Literary tie-ins arose with modern consumerism, and as historian Peter N. Stearns argues, this phenomenon first appeared in Western Europe even before the industrial revolution. Additionally, as my recent article on James Thomson’s book-length poem The Seasons demonstrates, modern consumerism was transforming literature into commercial products as early as the 1780s.*

Of pre-twentieth-century bestsellers, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was unique for two reasons. It was an American book, and it generated more tie-ins than any other pre-twentieth-century book. Almost all these goods were produced for the expanding transatlantic market of middle- to upper-class consumers. Because of the popularity of Uncle Tom, both the book and stage show, every manufacturer of products such as textiles, books, games, and other paper entertainment products, decorative arts including wallpaper, ceramics and metal work who could push goods by associating them with the novel or play did so. Now a look at the objects featured on the UTCAC site.

At the high end of consumer goods inspired by the novel stand some very expensive objects — a large piece of Berlin work or needlework featuring Uncle Tom and Eva, a girandole or candlestick, and Limoges spill vases. Though these objects are rarified in terms of their high prices, they participated fully in the popular culture of their day because of their subject matter and composition.

To hear song, click image.

To see handkerchief, click image.

German, Berlin work pattern (11¼ x 13½"), from Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.

Click image to enlarge.

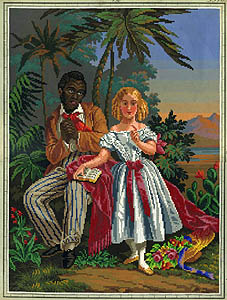

This Berlin worked, or needleworked, image of Uncle Tom and Eva probably occupied a central position on a wall. Berlin work refers to tapestries or needlework stitched with brightly colored wool following patterns printed in Berlin, Germany. In the mid-nineteenth-century marketplace, the Tom and Eva pattern was just one of over 40,000 patterns available. Most Berlin work came in sizes smaller than the Tom and Eva and featured animals, country life, or religious figures.*

German, Berlin work pattern (dimensions?), from Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.

Click image to enlarge.

Girandole of Uncle Tom & Eva, made by Dietz and Company, from Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.

Click image to enlarge.

DETAIL OF BASE

Because of its intricate detail and crystal, brass, and marble components, this girandole or candlestick manufactured by Dietz & Company of New York City would have been an expensive purchase. Despite the atypicality of its price, the girandole as well as inexpensive earthenware figures depended upon a hierarchy of size and bisymmetrical arrangement. In these girandoles and other decorative arts, literary characters are often paired, and this pairing replicates the construction of characters in their literary sources. Characters often appeared in duos: selfish and selfless, male and female, mother and child, civilized character and wilderness character — in the case of Last of the Mohican’s (right), and black and white — in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Such a dual system fitted nineteenth-century literary and aesthetic taste as well as cultural politics in which it took two to make a complete one. Paired figures are found on both inexpensive ceramic figures and this expensive girandole.

As this Last of the Mohicans group shows, the small figures of Major Heywood and his fiancée Cora formed the decorative ends to the suite, and in this composition, they oppose male and female. In the center stood a grouping including Natty Bumppo and Chingachgook. With this center, the tripartite composition establishes a hierarchy: first by inclusion and exclusion, second by placement, and third by size. Specifically, Mangua and the novel’s military figures do not appear on the mantel. With Natty and the Mohicans in the largest central grouping of figures, the overall design of this tripartite suite rates most highly the values carried by Natty, his Indian friends, and their relationship.

Click image to enlarge.

SEE PERIOD DINING ROOM

Limoges Spill Vases, c. 1850s

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.

Click either image to enlarge.

Like the girandoles, these spill vases from the Limoges region of France reside at the high end of Uncle Tom’s Cabin tie-ins. Both girandoles and vases were expensive discretionary purchases that well-to-do consumers alone could afford. It is impossible to know exactly when these vases entered the United States. They may have been used in France or England until their importation in the second half of the twentieth century by an American collector of Stowe-related or antislavery themed items.

The vases started their commercial life in the Limoges region of France, in the 1850s. There, factories produced durable porcelain that could be shaped in intricately fashioned molds and that when fired and glazed approached a pure white color. These particular vases were molded and given their first high temperature firing at the French factory. After the decoration to the main body was completed, the vases received a second firing at very high heat after which they were shipped to decorating studios and shops throughout Europe and the United States. New York City was first among American coastal cities as a center for porcelain finishing because it attracted immigrants from Europe with the skills necessary for completing the design.* In the United States, lower tariffs on undecorated ceramics and higher excise tariffs on decorated and painted ones called for this two-stage manufacturing process. In New York City shops, artists, usually women, painted the vases before they received a final firing at a lower heat. If you look carefully at the Limoges pieces, you will see that the material of the main vase has a high gloss finish, whereas the thematic figures in the center have a matte or lower gloss finish, resulting from the heat at which the vase was fired. To accommodate the pocket books and decorating exigencies of various customers, these spill vases were marketed in at least two sizes. Because the clay used for ceramics fired to a light, white color, that color became the base of the white characters’ complexions. After a first firing, an artisan tinted the complexion of white figures to make their coloring less monochromatic and more realistic. African Americans usually appear with less-nuanced complexions, as the fired white clay had to be covered first with a solid black or brown and subsequently detailed. In consequence, the shaded whiteness of the white figures’ complexions contrasts with the almost solid blackness of the African American figures’ complexions. Thus, the white color of the ceramic material itself comported with the idea of whiteness as normative among the buying population.

SEE DECORATING SHOP

In the urban-suburban world of the post-1850 United States, the distance of upper-middle-class residences from the urban life of their cities suggests distance of their genteel world from the popular culture of urban life. Despite the actual distance of the houses of the well-to-do classes from urban life, many of the objects that they contained received their inspiration from that source. For example, consider the choice of themes for the spill vases: the escape of Eliza across the Ohio River and the encounter of Tom and Eva in the St. Clairs’ garden. The composition for each vase appears to have been drawn directly from lithographs, an inexpensive art form for nineteenth-century homes. In turn, the lithographs had as their source images from the illustrations in a French edition of the novel. Thus, it is not the image of Uncle Tom and Eva that makes these vases exclusive; they were available to many people across a broad swath of income who lived in cities or their more economically exclusive suburbs. Rather, the appearance of this image on an expensive piece of media make these spill vases exclusive possessions.

Click to compare vase & illustration.

Click to compare vase & illustration.Also, note Tom’s costume. In the 1850s, reading and theatrical audiences immediately would have recognized his pink striped pants as quite suitable for a noble servant such as Tom (sometimes artists rendered the stripes in a flowered pattern). Scholar Harry Birdhoff explains that Tom’s costuming derives from the complication caused by the Tom plays’ immediate and widespread popularity. With the sudden popularity of Tom plays in 1853, theater troops suddenly had to produce costumes for their Tom characters. Clearly a ragged Jim Crow costume would not do. Therefore, stage productions drew, as Birdhoff explains, from the wardrobe for servants in other popular stage pieces. In this case, Tom borrowed from Don Giovanni’s loyal servant Leporello. Because Don Giovanni belonged to the 1850-1900 opera and concert repertoire, ceramic painters in the many cities where Don Giovanni and the Tom plays were performed would have been familiar with the Leporello character and his costuming. By dressing Uncle Tom in his costume, wardrobe mistresses, theater managers, and Limoges decorators made a convenient choice that carried iconographic significance.*

Tom and Eva, large white metal group, 10½" (width) x 9¼" (height), c. 1850s

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.

SEE STATUETTE IN 3D.

Without a strong ceramics industry in the 1850s, American three dimensional tie-ins appeared most commonly as metal figures, illustrated by this bronze image of Uncle Tom and Eva. Like the Limoges spill-vases and Berlin work, this metal sculpture commanded a high price. As a critic for the antislavery Liberator wrote, pieces such as this one had “an established market value.” With optimism that these meaningful pieces would replace merely decorative pieces, he wrote, “people of wealth and taste now begin to seek such works as the ornaments of their parlors and chambers.”* The high-end pieces that we have here all date from the 1850s, thus suggesting the rush of manufacturers to take advantage of the rage for Tom-themed things immediately following appearance of the novel and the first Tom shows. Manufacturers produced few high-end Tom-themed items from the 1870s through the 1890s, if the UTCAC website presents a representative selection of them. This shift in the post-Civil War period to less expensive Tom-themed items indicates that the inspiration for tie-ins also shifted from the novel itself to the Tom Shows, as the dramatizations came to be called after 1875. Their messages stem from the exigencies American racial politics that minimized the cultural potential of African Americans and maximized their cultural and physiognomic differences from white Americans.

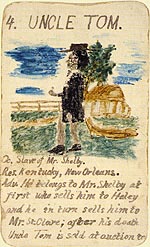

In the United States and Britain, commercial manufacturers of printed goods had responded immediately to the potential for Uncle Tom-themed items and in the post-Civil War years. They continued to produce a plethora of paper products to support domestic decoration and play — mainly paper dolls, board games, puzzles, and Author card games, throughout the nineteenth century and into the first decade of the twentieth century. Images of the novel’s characters and reproductions of its illustrations appeared as both inexpensive lithographs and more expensive mezzotints. The board games and Author cards seem to be produced by industrial commercial culture to facilitate the replication of a middle-class in which leisure, especially youthful leisure, rewarded the values and behaviors of the work world. Thus, the Tom-themed games constituted informal agents of adult intervention in youthful play. These games attempted to assure the replication of the values and behaviors of the industrial-commercial world that had produced them. As commercial products, the Tom game tie-ins belonged to a world in which domestic life was intended to offer opportunities for didactic play. Many mid-nineteenth-century domestic advice books for an audience aspiring to gentility recommend activities for parlor life. Some games relied on word play or performance and had no explicit connection to commercial culture. Other games relied upon commercial media and could not have existed without the production and distribution capacities of nineteenth-century industrialism. Nevertheless, both sorts of games depended on a particular set of behaviors that promised success in the surrounding world as much as in parlor games. To succeed at a board game in the nineteenth-century parlor, one had to have the will to compete, follow rules, respect and cooperate with one’s competitors, and persist. Uncle Tom-themed games sometimes put even more focus on certain of these values. An 1852 board game, for example, constructed winning as assembling three cards: Uncle Tom, Little Eva, and a third called Justice.* If parlor denizens played these games according to their official rules, the subversive potential of minstrel characters including Sam and Topsy would resemble that of a carnival sideshow. Players could be amused by Sam and Topsy, yet if the comic characters’ antics overwhelmed the player, that player would not win the game. To win, one had to follow the values and behaviors of the dominant characters and strive for reunification of one’s family. Here, we can quickly remember that these games centering on family wholeness receded in popularity in the early twentieth century. In those years, games appeared that we now recognize as precursors to the Parker Brothers’ Depression-era game Monopoly. All these twentieth-century games defined winning in terms of property accumulation. Instead of providing humor through the antics of Sam and Topsy, the game provided humor and excitement as characters suffered the vicissitudes of chance and business life.

This emphasis on the manufactured game process leads to a brief comment about the relationship between invention and commercially produced entertainment. The presence of manufacturing did not eliminate the ability of the parlor game player to intercede into the meaning of an object and to give it his or her own emphasis. For example, the game Authors was popular especially in the post-Civil War years. An edition of Authors contained British and American literary figures but rarely a woman figure, despite the achievements of Harriet Beecher Stowe. At right is an Uncle Tom’s Cabin card from a set of 42 drawn and colored by a child in 1862; he borrowed merely the idea of the game from the manufacturers.

Another story arises from the tableware and decorative pieces produced in Great Britain and inspired by the novel and Tom plays. Although the book and Tom stories were transatlantic phenomena, the unique histories of Britain and its former colony with regard to slavery, abolition, literacy, and industrialism determined the reception and use of the Tom paraphernalia in each country. While Southerners and their sympathizers criticized the novel in the United States, in Great Britain some representatives of the literary elite, manufacturing interests and upper classes feared the effects of the novel, as Amy Fisch has recently explained. She reminds us that the terms Tom-mania and Tomitudes originated as terms of derision aimed at undermining the transgressive power of the novel. She writes that the anti-Tom minority deplored that their countrywomen and men “were not consuming ‘Uncle Tom’ in the (ideological) ‘shapes’” that they preferred.*

To see puzzle, click image.

To see game, click image.

Click image to enlarge.

Until the late nineteenth-century, the United States imported most of its ceramic ware from Britain and France. From the very early nineteenth-century and into its last years, expensive porcelains and ceramics, such as table china for the White House table of the Lincolns, were manufactured in France, although their decoration, as we have seen, probably was finished in New York City.

An investigation of the Tom-themed tableware and decorative objects requires a major caution. Despite Americans’ dependence on the European market, not all American themed goods were intended for American consumption. The assumption that all Uncle Tom tie-ins appeared on the American scene at some point in the nineteenth-century is simply not true. As P. D. Gordon Pugh, the preeminent scholar of Staffordshire argues, Americans imported relatively few Staffordshire figures during the nineteenth century. Examination of a bibliography about Staffordshire figures and the Staffordshire potteries supports his contention. In each decade from 1890 until the 1950s, no more than two or three articles about these subjects were published in popular or scholarly journals per decade. Then during that the 1950s and the 1960s at least ten scholars published numerous articles on Staffordshire figures.* Thus, the importation of Uncle Tom figures seems to have been primarily a post-World War II occurrence. Most recently, a scholar has studied the invoices of American firms doing business with English potteries in the mid to late nineteenth-century. Of the import invoices that he found — admittedly a fraction of the total number — only one, from 1876, mentioned a Negro figure.*

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center,

Hartford, CT; and Courtesy Mary Schlosser.

Click any image to enlarge.

With regard first to the tableware, the ceramics that I am discussing include transferware plates that dealers today believe usually were sold in sets and for use. They would have been used in the dining area and not displayed in the parlor. Historians of transferware write that transfer decorated tableware reached its highest popularity in the United States before 1852. In the three decades before 1850, transfer printed ware comprised only 53% of imported ceramic ware, whereas in the 1852 period the share of printed ware shrank to 21.5%.* For most of the nineteenth century, American consumers preferred white-colored tableware known as granite ware. If this sort of pottery had décor, it was molded into the body of the vessel.

For transferware pieces, a skilled artisan, most often a male, at a pottery factory copied an illustration from an available engraving onto a copper plate. Women factory workers transferred this engraved design as well as border patterns to a ceramic blank to complete the print process. In the pre-1850s period, patterns made for the export market in the United States included scenes of notable buildings in American cities or of natural phenomena like Niagara Falls. The abolitionist crisis of the 1830s did lead to several significant patterns made especially for the American market including the “Lovejoy plate” (right), memorializing the abolitionist printer’s murder and the burning of his press in Alton, Illinois, in November, 1837.

British Uncle Tom transferware patterns exist among thousands of other patterns that included scenes of British landscape, buildings, and American landscape scenes. As a decorative arts scholar reminds us, wares printed with American themes resided “on the fringe of the trade.”* Of all available patterns, antislavery and Tom-themed plates probably comprise less than 1%. Their presence in American museums, historical houses, and private collections reflects more about the taste of professional and amateur collectors from the late nineteenth-century onward than about the preference of nineteenth-century consumers who lived through the rage for the novel.

A set of transferware, even of low-interest consumer items such as the Lovejoy and Uncle Tom patterns, included serving platters and vessels for meats, vegetables, and beverages including tea, coffee, and their accoutrements as well as main plate, dessert plate, soup bowl, and coffee or tea cup and saucer. Whether families bought an entire set for use or one or two pieces, we do not know. We also do not know to what extent families might have combined patterns as they set their tables. What is evident is that by the 1820s in both Britain and the United States, meal times had become occasions when members of households aspiring to genteel middle-class status no longer ate their food from a common dish. Instead, they shared time and space while participating in a mealtime performance. Each food item had its own serving vessel and each meal participant had his or her own eating vessels. Use of these items in a well-orchestrated meal was the goal and depended upon the diners’ and the servers’ knowledge of detailed conventions for presentation of multiple food courses in an orderly sequence. The specialized vessels reflect mid-nineteenth-century interest in fitting design to function, thus leading to an emphasis on individualization. Nevertheless, this individualization of the function of each serving piece — a manufacturer could sell more if it offered variety — took place within a unified, thematic whole. The pattern of the tableware united the various shaped pieces on a dining table. Thus, actual difference existed within a unified visual universe.*

Click image to enlarge.

3 Representative Staffordshire Figurines

Courtesy Elinor Penna.

http://elinorpenna.com

Now, this essay will turn to the Staffordshire figures on the UTCAC site. By the mid-nineteenth century, the area of Staffordshire in England, which comprised six villages, dominated the manufacture of pottery and especially inexpensive pottery. By the 1760s, the Staffordshire potteries had become major forces in the world market, and from the 1850s until the end of the century, they “dictated trends from North America to Australia.” From this region, Americans imported almost all of the inexpensive tableware used in hotels, restaurants and middle-to lower-class homes. Besides inexpensive tableware, the Staffordshire factories also produced figures of popular people, famous buildings, and animals, mostly for their countrymen. Like the Limoges spill vases, Staffordshire figures were produced from white clay. After the clay received a first firing, it was referred to as biscuit. Artisans, usually women, colored or decorated the white-colored pieces of biscuit. Areas with a white background, for example the complexions of white people or white clothing, received shading or decoration. White figures received tinted complexions and pink cheeks while pants received stripes. In the same manufacturing step, the artisans applied a solid color to coats, hats, animal fur, and African American skin. After firing the colors, the Staffordshire pieces were glazed and fired for a last time. Thus, the unvariegated complexions of African Americans (and other subjects thought of as black: shoes, hats, belts, and zebra stripes to name a few) were solid black. To make African Americans’ complexions more nuanced and realistic was not possible if the manufacturing process was to be kept inexpensive and the colors made durable. In fact, the African American Staffordshire figures that did receive a nuanced complexion over the solid black paint and then a fourth and final firing at a low temperature have faces and hands more likely to chip and flake (see example).

As with transferware, manufacturers of Staffordshire figures made a few items for the American market, although not all American-themed figures were made for export. The American figures produced include Constitutional or national figures (George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson), antislavery figures including John Brown and President Abraham Lincoln, and stage performers who toured Great Britain (Adah Menken in the 1860s), and the evangelists Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey, who toured Great Britain in 1872. Because the artisans sometimes mislabeled Franklin as Washington and vice versa (above right), it can be assumed that they were not intended for American buyers who would recognize and reject the mislabeled pieces. Again, no evidence suggests that American earthenware figures were intended primarily for export to the states, although a few may have made the transatlantic crossing in the luggage of travelers. The artisans who fashioned the molds for these figures selected subjects from the religious, political, military and reform interests of the day. They shaped the molds by copying published engravings or illustrations from British newspapers, sheet music (right), and even Berlin needlework patterns. One could find a figure to suit one’s taste whether Catholic or Protestant, Franco-phile or Anglo-phile, partial to the royal family or the republicanism of Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi. In England, these figures were sold throughout the countryside by peddlers and in the city through china and fancy goods stores as well as by street vendors, who cried their wares at parades and celebrations, funerals of national celebrities, and theaters.*

Click image to enlarge.

Composite image,

click to enlarge.

During the nineteenth century, Staffordshire figures belonged to British popular culture from the working classes at least through the middle classes from two decades before publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin through the late nineteenth century. Today, in the United States Staffordshire figures reside in the collections of museums or the homes of the upper classes with a taste for things British.

Despite having much to do with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Staffordshire figures, such as those on the UTCAC website, participated little as material artifacts in American popular culture. To appreciate their relationship to American popular culture, we must follow another route and start with the design of the novel. In her thought-provoking book, Uncle Tom Mania, Sarah Meer exposes how the comic devices of the book, such as the great horse chase orchestrated by Sam, replicate those of the minstrel show.* Let us imagine a circuit originating in the minstrel shows of the transatlantic urban world of the 1840s:

Figurine Vendors

Details from illustrations

Click either image to enlarge.

Harvard Theatre Collection.

Billings' Illustration of Topsy

(1853 Uncle Tom's Cabin)

Barrett Collection.

"Buy Image! Ballad" (Sheet music cover)

Lester S. Levy Collection.

Courtesy Elinor Penna.

In this setting, the Tom-show figure added to the meaning of a free-laborers’ home. Domestic display of objects also suggests that family and visitors shared admiration for the figures, whether aesthetic or sentimental, at least to the extent that they did not ridicule them. Thus the Tom plays shifted some of the novel’s content from a public setting to a domestic one after vitalizing the original content of the minstrel shows with thematic and action content drawn from the novel.

As the preeminent anthropologist Grant McCracken has explained, objects allow us to make our values visible. For example, one can think today of a hybrid car or compact fluorescent bulbs as having more meaning than mere economy; they also say something about our desire to be seen as environmentally virtuous. By themselves, goods have no intrinsic meaning and do not necessarily imply economic striving. Our purchases can confirm conventional beliefs, break them down, or even accomplish both ends. Because objects help to situate a person, décor can transform a house “into a place where a self lives,” as McCracken argues. Objects such as the Uncle Tom Staffordshire figures may merely recall a pleasant outing to a Tom play, or they may prompt family members and visitors about expected behavior. Certainly, the Tom figures gave their nineteenth-century owners cues about how to behave with regard to race.*

Staffordshire figures

Courtesy Rex Stark.

Click on any figure to enlarge.

An eye on the attenuated process of cultural transmission from minstrel show, to novel, to material culture, and finally to domestic display reveals the importance of popular culture to the art of Harriet Beecher Stowe as well as the values of both her readers and the audiences at Tom plays. Thinking about the role of minstrel shows and music in Uncle Tom’s Cabin makes visible the thorough involvement of Harriet Beecher Stowe with the urban life and popular culture of the 1840s and 1850s. Joan Hedrick’s masterful biography explained how her life as a mother and participant in a literary middle-class world educated her in writing and performance, in other words authorship. Yet, Hedrick’s biography does not disclose how Harriet knew about the minstrel show performances so thoroughly that she could insert this comic layer effectively into her novel. The alternatives are several: she learned through her reading, especially of the newspapers and journals of the day as illustrated by the advertisements in the MINSTRELSY SECTION of this archive, she consulted family friends, and/or she drew on her daily contact with her African American household help. Because these alternatives would have given her merely a vicarious experience of minstrelsy, the result might well have been a lifeless sideshow. Instead, let us imagine her as a visitor or resident of New York, Boston, and Cincinnati. Walking through the streets of those cities, she would have witnessed street minstrelsy and heard its songs while her doing errands and going to appointments. As a resident of Cincinnati in the 1840s, Stowe must have known of the performances of the many minstrel groups who performed in that city, including Christy’s Minstrels, the Sable Harmonists, and the Sable Troubadours.*

These Staffordshire earthenware figures thus represent an endpoint on a popular culture circuit. That circuit begins with the street culture of 1840s transatlantic America and Britain. There, among street peddlers, pickpockets, and prostitutes, Jim Crows danced and minstrels sang. During the next decade, minstrel shows gained a larger audience by losing some of their hard, racist edge and becoming more acceptable to genteel norms and introduction into parlor life. Then, the observant and inventive Harriet Beecher Stowe appropriated and incorporated minstrel humor into her novel. Finally, the novel spun off the Tom plays that in turn provided the models for Staffordshire earthenware figures.

Literal and figurative oceans of difference separated the purchaser of a Staffordshire memento in Britain from the purchaser of a Tom and Eva girandole in the United States. These huge differences in nationality, social-economic class, and levels of literacy and education obscure what the purchasers had in common. Despite the differences, people on both sides of the Atlantic and of great and little means had purchased a Tom figure for display in their homes, probably for a featured position on a mantel. This domestic display for family and friends contrasts absolutely with the absence of public displays of African Americans in civic culture, especially in American civic culture. Display of Tom tie-ins had to be intended to impress a selected circle of like-minded acquaintances rather than a larger public. In American cities, no sculpture of African Americans stood to instruct passers-by about civic virtue. As historian Kirk Savage first described, in the post-Civil War public space of American cities sculptural representations of African Americans were absent unless the portrayed African Americans appeared in inferior roles. For example, in Thomas Ball’s Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (1876) situated at Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., the slave figure appears as a kneeling supplicant before a beneficent Abraham Lincoln. Further, no statues commemorated the national service of 180,000 African American Civil War soldiers, with one exception (right). In that exception, the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial on Boston Common in Boston, Massachusetts, the marching African American soldiers of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment play the role of supporting characters to the heroism of their white commander astride a horse.*

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

Also note that the artisans who designed the girandoles, drew the Berlin work, and molded the earthenware figures, all chose to represent the spiritual mutual dependence and spiritual affinity of Tom and Eva. If one wants to know the essential meaning of the play or novel, here is an audience preference unmediated by book reviewers, cultural critics, or any authority other than the logic of the marketplace. In this scene of sentiment, the stark contrasting of African American blackness versus the white of the clothing that both Tom and Eva don reminds us that British and American Victorians looked forward to a specific racial unity — one forged according to the terms of whiteness. They hoped that white civilization would mask racial differences. The material culture of Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped white British and American Victorians conspicuously display the virtues that they prized in themselves and their culture. They wished for an interracial harmony that did not challenge the norm of whiteness prevailing in material culture and among the majority population.

SEE STATUETTE IN 3D.