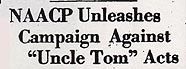

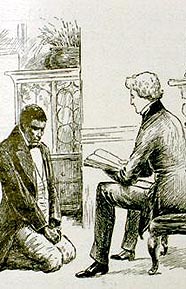

TOM PRAYING FOR HIS MAS'R

TO SEE ENTIRE IMAGE CLICK HERE

1925 PULLMAN PORTERS'

UNION CARTOON

ENTIRE IMAGE

1945 BILLBOARD ARTICLE

ENTIRE

ARTICLE

|

In Flight to Canada (1976), Ishmael Reed's revisionary

send up of Stowe's novel, one moment shines a brilliant light on the cultural

power of the figure of Uncle Tom. Raven Quickskill, a fugitive slave, has been caught

by the two Tracers his master hired to bring him back to slavery. Quickskill notices

one of the men has a cold, and offers to get him some vitamin C from the

bathroom. While the men look over a copy of Uncle Tom's Cabin -- "I

hear [Stowe] made a pile on this book," one says -- he goes into the bathroom

and out the window, recovering his freedom.* The Tracers would not normally let Quickskill out of their sight, but they

can believe a black man would be more concerned about a white man's cold than the threat to his own

liberty. As far-fetched as this notion might sound, Reed really didn't have to go very far to find it.

Right there in the novel the Tracers are looking at is the scene in Chapter 28, for example, in which Tom tells St.

Clare that even if St. Clare frees him, his freedom and family can wait until "mas'r" has no further use

for him: "I'll stay as long as Mas'r is in trouble."

St. Clare's "trouble" is spiritual. The vitamin Tom provides is his great spirituality, which

paradoxically is the result of his extraordinary deprivation. After he was sold, he tells St. Clare one

chapter earlier, "I felt as if there weren't nothin' left." Out of this suffering comes his faith --

"I's so happy, and loves everybody, and feels willin' jest to be the Lord's" -- and this faith he

makes available to the white man who has lost his child: "I know He's willin' to do [the same] for

Mas'r." In fact, St. Clare is saved by Tom -- though Tom is never freed by St. Clare.

In the novel Tom is not an "Uncle Tom," which the dictionary defines as a black person

who abjectly sells out the interests of his race to curry favor with the white power structure.

Malcolm X's speeches and his Autobiography are probably most directly responsible for

giving the term the rhetorical force it has today. As far as I've been able to discover, this

idea of "an Uncle Tom" first emerges during the years immediately after World War I. Beginning

in 1919, Marcus Garvey and his followers made "Uncle Tom is dead" one of the slogans of their

nationalist movement. In the mid-1920s, the campaign that A. Philip Randolph led

to unionize the Pullman porters repeatedly stigmatized those who opposed them as "Uncle Toms"

serving the bosses. (The archive contains a

SECTION with examples of these early

20th century texts and images.)

It's not clear to me how this usage came about. In the novel Tom never betrays

other blacks. The first time Simon Legree whips him, it's because Tom will not obey the order

to whip Lucy, and Legree beats him to death because Tom will not reveal where Cassy and Emmeline

are hiding.

|

On the other hand, Tom is very willing to sacrifice himself to help others,

white or black. Stowe would call this "Christian," and in theory sets it up as the ideal everyone

should aspire to. Eva, for example, is equally selfless when she tells Tom "I would be glad to die,

if my dying could stop all this misery" caused by slavery. But I propose to call what

Tom winds up doing in the novel "Tomming" -- a term I'm borrowing from the actors who

dramatized the novel to call attention to the fundamental perverseness of Stowe's narrative. As she

wrote in her 1878

INTRODUCTION, Stowe began the novel with a vision of a black man dying in

agony on a southern plantation, and wrote it, of course, to urge white readers to help black slaves.

But when Tom gets to the St. Clare household in the story's middle section, the narrative emphasis

shifts, though Stowe and her readers were probably unconscious of the change:

while Tom never stops wanting to be free and reunited with his family, he comes to seem even more

anxious to help the whiter characters, even the ones who "own" him, with the burdens of their

lives.

|

TOM TELLS ST. CLARE

GOD WILL EASE HIS PAIN

ENTIRE IMAGE |

He saves Eva from drowning, but far more importantly teaches her about religion.

He saves St. Clare from alcohol, and then, far more importantly, after Eva's death leaves St. Clare

"bitter" and even more estranged from the faith his dead mother had tried to teach him, Tom saves his

soul too. This pattern is repeated again at Legree's, where the "bitter" character is Cassy. Tom is

beaten for the first time in Chapter 33. The next chapter, "The Quadroon's Story," begins with Cassy

ministering to his bruised body, but as the chapter title suggests, it quickly turns from Tom's

suffering to hers, and ends up with him ministering to her broken heart and aching soul. And what

happens in this one chapter -- that Tom's pain turns out to be the source of his ability to heal

someone else, whose sufferings command more of the narrative's and the reader's attention -- is what I

think happens at large in Uncle Tom's Cabin. In this story, paradoxically, it is the "lowly"

and disenfranchised black man's role to free others from their sorrows.

Stowe did make a lot of money from the novel. It was so popular, I suspect, in large

part because of the way Stowe, even as she makes her powerful case against the institution of

slavery, winds up scripting a racial fantasy in which the black man remains, willingly, in such a subservient

position, raising up someone else with the resources that have been nurtured in the

depths of his own suffering. Such a narrative not only legitimizes the black man's deprivation, and

so saves white America from feeling responsible or guilty about the socio-economic hardships blacks

have faced; it

makes that "blackness" available to white Americans while maintaining their privileged position as

the group whose lives really matter.

|

The Little Colonel (1935)

© TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX PICTURES

DIRECTED BY DAVID BUTLER | BASED ON A STORY BY ANNIE FELLOWS JOHNSTON

This film contains one of the Thirties' most famous musical numbers: the "stair dance" Bill "Bojangles"

Robinson does with Shirley Temple. The clip at left comes immediately before he starts dancing,

and reveals why he dances: to cure "Miss Lloyd" of her homesickness. She's the "Little

Colonel," sent to her grandfather's Kentucky mansion by the illness of her father. Robinson plays

"Walker." Since the film takes place just after the Civil War, he's Col. Lloyd's servant, not his

slave. And he cures the white child with his wonderful body, not his soul. But in both this film and

The Littlest Rebel (also 1935) the Robinson-Temple pairing is incredibly close to the relationship

Stowe defines between Tom and Eva, and the role the black male plays in serving the needs of the otherwise more

privileged white child is exactly the same.

This film contains one of the Thirties' most famous musical numbers: the "stair dance" Bill "Bojangles"

Robinson does with Shirley Temple. The clip at left comes immediately before he starts dancing,

and reveals why he dances: to cure "Miss Lloyd" of her homesickness. She's the "Little

Colonel," sent to her grandfather's Kentucky mansion by the illness of her father. Robinson plays

"Walker." Since the film takes place just after the Civil War, he's Col. Lloyd's servant, not his

slave. And he cures the white child with his wonderful body, not his soul. But in both this film and

The Littlest Rebel (also 1935) the Robinson-Temple pairing is incredibly close to the relationship

Stowe defines between Tom and Eva, and the role the black male plays in serving the needs of the otherwise more

privileged white child is exactly the same.

|

Dumbo (1941)

© 1941 WALT DISNEY PICTURES

DIRECTED BY BEN SHARPSTEEN

The racial subtexts of this 90-minute animated feature are complex. Dumbo's big ears mean

he is an African elephant, and his story catches up much in the experience of African Americans with slavery and racism.

Because of his ears he is, as his friend the mouse says, "socially washed up," and "worst of all, turned into a clown,"

while the sentimental scene of him being separated from his mother recalls many moments in Stowe's novel. But two

things keep us from seeing Dumbo himself as "black": his big blue eyes, and his meeting with the crows. The racial subtexts of this 90-minute animated feature are complex. Dumbo's big ears mean

he is an African elephant, and his story catches up much in the experience of African Americans with slavery and racism.

Because of his ears he is, as his friend the mouse says, "socially washed up," and "worst of all, turned into a clown,"

while the sentimental scene of him being separated from his mother recalls many moments in Stowe's novel. But two

things keep us from seeing Dumbo himself as "black": his big blue eyes, and his meeting with the crows.

That meeting provides this movie with its "Tomming" episode. The crows themselves are created in the image of minstrel show

"darkies," but when they say they're "fixin' to help" Dumbo we hear the way Stowe defines Tom's role. While Tom shares

his faith, they give Dumbo a black feather and enable him to fly, lifting him out of the despair into which

he has fallen. From that point on, though, he quickly leaves the

"blackness" they represent behind: he gets even with those who ostracized and abused him (something blacks would not be

allowed to do), and goes off as the star of the circus. Everyone is reunited, except the crows, who wave

goodbye as the circus train disappears into the setting sun.

Sadly, but given the history of race in America not surprisingly, the film

can imagine a mouse and an elephant as best friends, but cannot conceive a place in

the circus for the crows, even though it was their help that saved Dumbo.

(Click on

image to see clip.)

|

Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

© 1989 WARNER BROS. PICTURES

DIRECTED BY BRUCE BERESFORD

Based on the Pulitzer Prize winning play by Alfred Uhry (1987), this movie

also won the Oscar for Best Picture (1989). Like Uncle Tom, Hoke (played by Morgan Freeman) is hired to

be a chauffeur. Though she's an old woman, not a young girl, like Eva, Daisy Werthan (Jessica

Tandy) lives in a southern mansion and needs Hoke's help. When her temple is bombed, for example, Hoke tells

her the story of the time he saw his friend's father lynched: sharing his "black" pain eases the burden of her

"white" suffering. The 30-second clip at left is from the film's the penultimate scene. Suddenly senile, Daisy needs

Hoke's help more than ever. When she tells him he's her best friend, we see how she remains the one empowered to

tell him what his role is, and as the camera moves away from this couple, it's amazing how much the visual imagery echoes Eva and

Tom (whom Stowe also calls Eva's "closest" friend as her helps her with her dying). Based on the Pulitzer Prize winning play by Alfred Uhry (1987), this movie

also won the Oscar for Best Picture (1989). Like Uncle Tom, Hoke (played by Morgan Freeman) is hired to

be a chauffeur. Though she's an old woman, not a young girl, like Eva, Daisy Werthan (Jessica

Tandy) lives in a southern mansion and needs Hoke's help. When her temple is bombed, for example, Hoke tells

her the story of the time he saw his friend's father lynched: sharing his "black" pain eases the burden of her

"white" suffering. The 30-second clip at left is from the film's the penultimate scene. Suddenly senile, Daisy needs

Hoke's help more than ever. When she tells him he's her best friend, we see how she remains the one empowered to

tell him what his role is, and as the camera moves away from this couple, it's amazing how much the visual imagery echoes Eva and

Tom (whom Stowe also calls Eva's "closest" friend as her helps her with her dying).

|

The Green Mile (1999)

© 1999 WARNER BROS. PICTURES

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY FRANK DARABONT

Based on the 1997 novel by Stephen King, this 1999 nominee for Best

Picture was a huge box office success. Its story generates considerable power by combining two

deeply-held stereotypical images of the black male: the buck and the uncle. John Coffey (played by

Michael Clarke Duncan) is, like Uncle Tom, a "behemoth." As someone on death row awaiting execution for a

crime he didn't commit, he's in circumstances as dire as Tom's enslavement. Nonetheless, like Stowe's, the

story expects him to keep saving white people. When he heals prison guard Paul Edgecomb (Tom Hanks) of a

crippling urinary tract infection, the white man goes home and has sex with his wife four times in one night

-- thus evoking the sexual prowess of the "buck" even while healing the sick like the original "JC." The clip

at left, though, comes from the end of the scene in which

John is taken out of prison to (as he puts it) "hep a

lady." The white woman is Melissa Moores (Patricia Clarkson), wife of the warden. Like Eva, Miss Lloyd and

Miss Daisy, she lives in a southern mansion, and especially like Eva she is dying (of a tumor). When John

enters her bedroom and sucks the disease out of her by kissing her as she lies in bed while a group of white

men stand around watching, the movie exploits our cultural anxieties about interracial sex, but finally the

relationship is the one defined by Uncle Tom and Little Eva, in which the black man acts with no

other desire than to "hep." Once the "lady" is saved, John goes back to prison, one day closer to his

execution. See if you don't recognize Eva and Tom again in the way the film visually defines the relationship

between the white woman and the black man. Based on the 1997 novel by Stephen King, this 1999 nominee for Best

Picture was a huge box office success. Its story generates considerable power by combining two

deeply-held stereotypical images of the black male: the buck and the uncle. John Coffey (played by

Michael Clarke Duncan) is, like Uncle Tom, a "behemoth." As someone on death row awaiting execution for a

crime he didn't commit, he's in circumstances as dire as Tom's enslavement. Nonetheless, like Stowe's, the

story expects him to keep saving white people. When he heals prison guard Paul Edgecomb (Tom Hanks) of a

crippling urinary tract infection, the white man goes home and has sex with his wife four times in one night

-- thus evoking the sexual prowess of the "buck" even while healing the sick like the original "JC." The clip

at left, though, comes from the end of the scene in which

John is taken out of prison to (as he puts it) "hep a

lady." The white woman is Melissa Moores (Patricia Clarkson), wife of the warden. Like Eva, Miss Lloyd and

Miss Daisy, she lives in a southern mansion, and especially like Eva she is dying (of a tumor). When John

enters her bedroom and sucks the disease out of her by kissing her as she lies in bed while a group of white

men stand around watching, the movie exploits our cultural anxieties about interracial sex, but finally the

relationship is the one defined by Uncle Tom and Little Eva, in which the black man acts with no

other desire than to "hep." Once the "lady" is saved, John goes back to prison, one day closer to his

execution. See if you don't recognize Eva and Tom again in the way the film visually defines the relationship

between the white woman and the black man.

|

The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000)

© 2000 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

DIRECTED BY ROBERT REDFORD

In this film, based on a 1999 novel by Steven Pressfield, it's a white man who

needs "hep." Rannulph Junuh (played by Matt Damon) also lives in a southern mansion (this time in Savannah,

Georgia). The mansion, though, and Junuh have fallen on very dark times. Once a champion golfer, he's become

a psychically wounded veteran of

World War I who has, as the film puts it both literally and metaphorically, "lost his swing." In his personal

darkness -- as you'll see in the clip at left, literally out of that darkness -- comes black "Bagger

Vance" (Will Smith). The religiosity here has been updated -- John Coffey's initials point to Tom's

Christianity, but Bagger Vance's name points to the Bhagvat Gita and eastern spirituality -- but the

plot line is exactly the same. The black man heals the white one, and all he asks in return is "$5 guaranteed" as his caddying

fee. At the end he goes off into the sunset, while Junuh gets the girl and the mansion. In this film, based on a 1999 novel by Steven Pressfield, it's a white man who

needs "hep." Rannulph Junuh (played by Matt Damon) also lives in a southern mansion (this time in Savannah,

Georgia). The mansion, though, and Junuh have fallen on very dark times. Once a champion golfer, he's become

a psychically wounded veteran of

World War I who has, as the film puts it both literally and metaphorically, "lost his swing." In his personal

darkness -- as you'll see in the clip at left, literally out of that darkness -- comes black "Bagger

Vance" (Will Smith). The religiosity here has been updated -- John Coffey's initials point to Tom's

Christianity, but Bagger Vance's name points to the Bhagvat Gita and eastern spirituality -- but the

plot line is exactly the same. The black man heals the white one, and all he asks in return is "$5 guaranteed" as his caddying

fee. At the end he goes off into the sunset, while Junuh gets the girl and the mansion.

|

Save the Last Dance (2001)

© 2001 MTV PICTURES

DIRECTED BY THOMAS CARTER

This film didn't get nominated for any prestigious awards, but it did make a fortune

for MTV, proving that the Tomming archetype is as popular as ever with the next generation. The story is set

almost entirely in the black inner city, ordinarily a place white America would rather forget about than visit.

But the movie does an extraordinary thing in its first couple minutes. As the opening credits roll,

scenes of Sara Johnson (Julia Stiles) taking the train into Chicago

from the white suburban world she has lived in are intercut

with scenes of her mother's death some weeks earlier. By the time she gets to the black neighborhood

where her divorced father (a jazz musician) lives, her private loss has over-written the decades of racial

discrimination and neglect suffered by the blacks who live in South Side. Rather than a problem for white

America, the black world of the inner city has become the place where Sara will be healed. This film didn't get nominated for any prestigious awards, but it did make a fortune

for MTV, proving that the Tomming archetype is as popular as ever with the next generation. The story is set

almost entirely in the black inner city, ordinarily a place white America would rather forget about than visit.

But the movie does an extraordinary thing in its first couple minutes. As the opening credits roll,

scenes of Sara Johnson (Julia Stiles) taking the train into Chicago

from the white suburban world she has lived in are intercut

with scenes of her mother's death some weeks earlier. By the time she gets to the black neighborhood

where her divorced father (a jazz musician) lives, her private loss has over-written the decades of racial

discrimination and neglect suffered by the blacks who live in South Side. Rather than a problem for white

America, the black world of the inner city has become the place where Sara will be healed.

Tom in this story is named Derek Reynolds (Sean Patrick Thomas). His character has been updated too, and a bit

more attention is paid to the conditions of his life as a young man trying to outgrow a wild adolescence and

get to college and med school. He's every bit as intelligent as Sara, and they wind up lovers. But

despite these

"revisionary" elements, her story remains the focal point, and his role in her story remains the familiar one.

He's a great dancer; the hip hop lessons he begins giving Sara in the clip here allow her to appropriate

"blackness" as the attitude that will heal her pain and get her admitted to Julliard. That's still in a city, of

course, but a long way from the inner city. The film leaves that behind with her.

|

Far From Heaven (2002)

© 2002 FOCUS FEATURES

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY TODD HAYNES

Julianne Moore plays Cathy Whitaker, whose mansion is in the northern suburbs rather

than the south. Socio-ecomically she couldn't be more privileged, but her husband's homosexuality makes her

leisured life an ongoing anguish. When her suffering is at its worst, she goes around the corner of her house, and

there, in the darkness, is her gardener, Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haysbert), speaking the line that never seems to

get old: "Is there anything I can do?" (Click on

image at left). Julianne Moore plays Cathy Whitaker, whose mansion is in the northern suburbs rather

than the south. Socio-ecomically she couldn't be more privileged, but her husband's homosexuality makes her

leisured life an ongoing anguish. When her suffering is at its worst, she goes around the corner of her house, and

there, in the darkness, is her gardener, Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haysbert), speaking the line that never seems to

get old: "Is there anything I can do?" (Click on

image at left).

There is. The film tries to disguise the stereotypicality of his role by making him a very sophisticated

gardener, and does include the story of what he and his daughter suffer as a result of 1950s white racism. Yet the

essential elements remain the same. When prejudice drives him out of town, his departure is depicted as an unhappy

ending -- for her story, which is still the one that matters.

|

About Schmidt (2002)

© 2002 NEW LINE CINEMA

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY ALEXANDER PAYNE

Based on a novel by Louis Begley (1996), this film shows how easy it is to tap into the

Tomming archetype. You don't even need to hire a black actor; you can just point in the direction of Africa and

blackness. Based on a novel by Louis Begley (1996), this film shows how easy it is to tap into the

Tomming archetype. You don't even need to hire a black actor; you can just point in the direction of Africa and

blackness.

Jack Nickolson plays Warren R. Schmidt, a very white midwesterner who realizes upon retiring from his job as an insurance

executive just how empty and futile his life is. (The symbol of a vacuum cleaner sucking air sums up what there is

to say "about Schimdt.") In the depths of this despair, he responds to a TV ad and becomes a foster parent to

Ngudu, a Tanzanian orphan. (The picture at left is the only time Ngudu appears in the film, and is the only

black face we ever see on screen.) Just as Mrs. Whitaker can only share the pain of her well-furnished life with Raymond,

so the letters Schmidt sends Ngudu along with the monthly checks to CHILDREACH become his

only emotional outlet. The film is too bleak to enable Schmidt to be saved, but in its final scene (here)

Ngudu, or rather the very idea of his blackness, does provide him with his only moment of deep feeling. Schmidt gets a

letter from a European nun who works at the Tanzanian orphanage, assuring him that Ngudu "wants very much your

happiness," and inclosing a drawing from the boy. Schmidt has

not cried at his wife's death, or the discovery of her infidelity, or the estrangement of his daughter, but Ngudu's

picture of the two of them together moves him to tears. It's a very affecting moment, but while

the emotion being felt depends on the history of disease, poverty and exploitation that "Africa" evokes, the tears

are all for the white man himself.

|

Bulworth (1998)

© 1998 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX

WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY WARREN BEATTY

Of all the films in this exhibit, Beatty's is the most like Stowe's novel in the way

its racial good intentions are tangled up in racist projections and stereotypes. In his comments about the film,

Beatty repeatedly and sincerely said he made it to dramatize the plight of the black inner city. But just as Stowe

was finally most deeply invested in St. Clare and Cassy's grief as parents who have lost children, so Beatty's

central concern is the way aging has unmanned Senator Jay Bulworth. The opening credits (left) depict him

attempting to watch a re-election campaign commercial through the tears he sheds for himself. Of all the films in this exhibit, Beatty's is the most like Stowe's novel in the way

its racial good intentions are tangled up in racist projections and stereotypes. In his comments about the film,

Beatty repeatedly and sincerely said he made it to dramatize the plight of the black inner city. But just as Stowe

was finally most deeply invested in St. Clare and Cassy's grief as parents who have lost children, so Beatty's

central concern is the way aging has unmanned Senator Jay Bulworth. The opening credits (left) depict him

attempting to watch a re-election campaign commercial through the tears he sheds for himself.

Believing he has nothing to lose, Bulworth's rebirth begins when he decides to tell the

truth about the power of corporate money in American politics to an audience in a black urban church. From that point on he descends

more and more deeply into "blackness," exchanging his suit for the costume of a gangsta rapper, and (as you can

hear in the clip at left) his bland rhetoric for the insistent rhymes and "obscenities" of rap. Believing he has nothing to lose, Bulworth's rebirth begins when he decides to tell the

truth about the power of corporate money in American politics to an audience in a black urban church. From that point on he descends

more and more deeply into "blackness," exchanging his suit for the costume of a gangsta rapper, and (as you can

hear in the clip at left) his bland rhetoric for the insistent rhymes and "obscenities" of rap.

What we are meant to hear in the clip is the repressed truth about how hard black Americans' lives are, but at the same time

it's easy to hear how empowering the white Senator finds the "blackface" he's wearing.

The previous clip ends with the image of real black males looking impressed with

Bulworth's protest against the inequalities they live with. But as you might expect, solving the problem of

one's impotency by "becoming black" ultimately depends on sex. That's where Halle Berry comes in, playing Nina, a

resident of South Central who is originally hired to assassinate Bulworth but ends up falling in love with him. He takes off the

gangsta outfit, but when she anoints him as her black man his story reaches its happy ending (here). The previous clip ends with the image of real black males looking impressed with

Bulworth's protest against the inequalities they live with. But as you might expect, solving the problem of

one's impotency by "becoming black" ultimately depends on sex. That's where Halle Berry comes in, playing Nina, a

resident of South Central who is originally hired to assassinate Bulworth but ends up falling in love with him. He takes off the

gangsta outfit, but when she anoints him as her black man his story reaches its happy ending (here).

Right after Bulworth kisses Nina, he is assassinated by one of the flunkeys

of corporate privilege. The image at left isn't a link to a clip, because in a sense this one image already

says too much to sum up. Visually, the scene echoes the famous news photograph of Martin Luther King's

assassination (COMPARE IMAGES).

Shocking as this appropriation is, the film's reviewers don't seem to have noticed it, perhaps because of all the

racial borrowing that has already gone on. In this story the "black man" who saves Bulworth is the one he himself

becomes, temporarily. Of course, nothing has changed for the real blacks who live in the South Central "hood"

that Bulworth descends into. Ultimately it's easier for Beatty to martyr Bulworth than to take the story one

step further in the direction of the social change that King died for. Right after Bulworth kisses Nina, he is assassinated by one of the flunkeys

of corporate privilege. The image at left isn't a link to a clip, because in a sense this one image already

says too much to sum up. Visually, the scene echoes the famous news photograph of Martin Luther King's

assassination (COMPARE IMAGES).

Shocking as this appropriation is, the film's reviewers don't seem to have noticed it, perhaps because of all the

racial borrowing that has already gone on. In this story the "black man" who saves Bulworth is the one he himself

becomes, temporarily. Of course, nothing has changed for the real blacks who live in the South Central "hood"

that Bulworth descends into. Ultimately it's easier for Beatty to martyr Bulworth than to take the story one

step further in the direction of the social change that King died for.

|

Right after Bulworth kisses Nina, he is assassinated by one of the flunkeys

of corporate privilege. The image at left isn't a link to a clip, because in a sense this one image already

says too much to sum up. Visually, the scene echoes the famous news photograph of Martin Luther King's

assassination (

Right after Bulworth kisses Nina, he is assassinated by one of the flunkeys

of corporate privilege. The image at left isn't a link to a clip, because in a sense this one image already

says too much to sum up. Visually, the scene echoes the famous news photograph of Martin Luther King's

assassination (