|

I first read Uncle Tom's Cabin in junior high school in the 1960s, but my own serious research into the nineteenth century's best-selling novel commenced in the 1980s. Interested in the history of derogatory anti-black stereotypes (see Figures 1 & 2, right), my focus then was on the second line materials, the plays, Tomitudes, movies, sheet music, classic comics, all of the mass mediated objects and performances that remained in vogue for so long after the original publication of Stowe's masterpiece. The case can be made that these diverse and diverting objects held more sway regarding what many in the U.S. and indeed throughout the world think about blacks, slavery, the Underground Railroad, abolitionism than Stowe's original novel, slave narratives, and probably serious history books of the era.

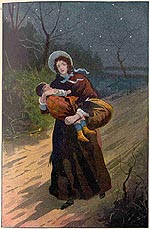

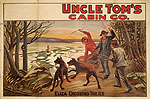

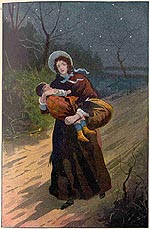

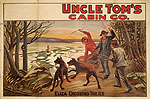

Although Uncle Tom's Cabin and the spinoffs and tie-ins remain fixtures in my courses about racial stereotypes, I've only done a smattering of research since the publication of my book Ceramic Uncles and Celluloid Mammies in 1994.* Most recently, I've been writing on seemingly different subjects more rooted in my training as a folklorist, namely African-American quilters and rumors and contemporary legends that circulate in the African-American community. As I was constructing the argument for one of the chapters of a book on African-American quilters, I found myself ferreting out all of my yellowed notes on Uncle Tom's Cabin and perusing library holdings in order to bring myself up-to-date on manuscripts that had been published on the book, its spin-offs and tie-ins since the early 1990s. I've concluded that there exists a provocative connection between a contemporary controversy about African-American quilt history and one of the more intriguing subplots in Uncle Tom's Cabin, which went on to become an essential component of the Tom Shows. This subplot—the story of the Harris family and its escape along the Underground Railroad (Figure 3)—was one of the most popular elements of the Tom Shows and many of the adaptations of the original novel.

In order to make this connection I'm going to begin with a consideration of the Harris story—particularly Eliza's story—as it unfolds in the novel. Then I'm going to focus on the way in which it becomes an indispensable component of the plays and other spin offs. Although the Tom Shows and eventually movies, particularly all of the very successful musical productions of The King and I (below) kept it alive, I want to ponder what features of the narrative coalesced to make it persistently attractive. Historians agree that in the second half of the nineteenth century and for most of the twentieth, folks who could tell a story of the Underground Railroad could tell Eliza's story. But I argue that it is no longer the dominant narrative about the Underground Railroad. Eliza's escapade has been replaced by a similarly sensational story in which quilt blocks, not blocks of ice, save a deserving heroine. In this post civil rights movement era, Eliza, and indeed all of the characters of Uncle Tom's Cabin, no longer fit as snugly as they once did. Now another kind of story tends to stick.

|

From the sublime...

To...

CLICK IMAGES TO ENLARGE

|

|

The Novel

The novel Uncle Tom's Cabin has forty-five chapters. In chapter seven Stowe continues the subplot introduced in the first chapter featuring the unfortunate enslaved family of George, Eliza and baby Harry Harris(Figure 5). With George already driven to seek security in the free states, Eliza is desperate to sabotage the sale of their child. Stowe depicts Eliza's dilemma:

A thousand lives seemed to be concentrated in that one moment to Eliza. Her room opened to a side-door to the river. She caught her child and sprang down the steps towards it. The trader caught a full glimpse of her, just as she was disappearing down the bank; and throwing himself from his horse, and calling loudly on Sam and Andy, he was after her like a hound after a deer. In that dizzy moment, her feet to her scarce seemed to touch the ground, and a moment brought her to the water's edge. Right on behind they came; and nerved with strength such as God gives only to the desperate with one wild cry and flying leap she vaulted over the turbid current by the shore on to the raft of ice beyond. It was a desperate leap—impossible to anything but madness and despair; and Haley, Sam and Andy, instinctively cried out and lifted up their hands as she did it.

&nsbp; The huge green fragment of ice on which she alighted pitched and creaked as her weight came on it but she stayed there not a moment. With wild cries and desperate energy she leaped to another and still another

cake;—stumbling,—leaping,—slipping—springing upwards again! Her shoes are—gone her stockings cut from her feet—while blood marked every step; but she saw nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side and a man helping her up the bank.

In chapter eight Stowe refers to Eliza's Escape in a chapter by that name summarizing:

Eliza made her desperate retreat across the river just in the dusk of twilight. The grey mist of evening, rising slowly from the river, enveloped her as she disappeared up the bank, and the swollen current and the floundering masses of ice presented a hopeless barrier between her and her pursuer.

|

DETAIL: CLICK

IMAGE TO ENLARGE

|

|

Fergus Bordewich, in his award-winning, Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement, characterized the sequence as, "The single most memorable passage in the novel, indeed in all nineteenth century literature to readers of the day and one that inspired countless previously neutral Americans to embrace the cause of abolitionism . . ."* As she had with the character of Tom himself, Stowe grounded the episode of Eliza and baby Harry in real slaves. In the winter of 1838, a fugitive slave woman and an infant child did cross the semi-frozen Ohio River and were able to find protection in the home of John Rankin, an active "station" on the Underground Railroad. The female slave who appeared at the Rankin's station was dark, heavy-set, and had left a husband and other children behind in slavery, willing to leave them behind with only the vague hope that she'd some day be able to return and either help them escape or buy their freedom.

In order to make the story even more likely to arouse the sympathy of her readers, Stowe crafted a more heroic runaway slave woman (Figure 6). Her Eliza was a beautiful, light-complected house servant whose similarly light-skinned husband George was a highly skilled slave on a neighboring plantation. George had already been driven to flee so that when her master, the financially-strapped Mr. Arthur Shelby, sells Harry, she has no familial obligations. Thus Stowe's gentle readers could not condemn the fictional Eliza as selfish and callous, but rather as a heroic loyal servant—a temporary single parent—forced to protect her only child.

Students of Uncle Tom's Cabin know that the novel was written in response to the enforcement spectacles triggered by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Fugitives who had utilized what was beginning to be called the Underground Railroad were being vigorously pursued and sent back in to slavery, abolitionists and other sympathizers who endeavored to assist runaway slaves were subject to punishment and even free blacks were further in danger of being sold into slavery. With the dramatic accounts of the fictional members of the Harris family, Stowe was naming and characterizing those who opted to pursue the Underground Railroad. She rendered them with attributes her readers would respect: light complections, strong work ethics, monogamous family ties, Christian values. As noted above, Eliza crosses the ice in the eighth chapter of a forty-five chapter novel. While Stowe gives her readers a satisfying story of one worthy slave family's success on the Underground Railroad, she knew she needed to focus the reading public's attention on the majority, not on the thousands who did manage to run away, but on the millions who endured the peculiar institution from birth to death. As its title suggests, the novel is about Uncle Tom (see covers below).

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

|

|

The Tom Shows: The Rising of Eliza Harris

The renewed critical interest in Stowe's novel, including this digital archive, testifies to the long-lived success of Uncle Tom's Cabin and the characters she created. As of June 24, 2007, the top selling edition of

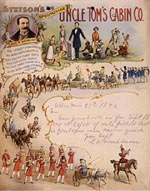

Uncle Tom's Cabin had an Amazon sales ranking of 8,042. In the nineteenth century, the novel was so popular that it triggered numerous stage productions, making Stowe's story the most commonly produced theatrical program from the mid 1850s until at least the beginning of the twentieth century (Figures 11 & 12). Theatrical versions of Uncle Tom's Cabin were so popular they spawned their own vocabulary. They were called Tom Shows, and the actors and actresses who performed in them were called Tommers. With ramshackle props, crude costumes, and flimsy scenery, Tommers crisscrossed rural and urban America, mounting the play anywhere they might be able to entice an audience. Theatres and stages were optional; inveterate Tommers would perform in barns or railroad stations. When motion pictures came into vogue Tom Shows continued to travel throughout the country.

In 1852 what was probably the first adapation of the novel was staged at the National Theatre. As was true for so many of the productions that followed, its scribes took extraordinary liberties with Stowe's novel. The production at the National Theatre had musical numbers and in the end Tom and the Harris couple (Edward and Morna Wilmot) were restored as free blacks to the original Shelby plantation. Although this rendition did not feature Topsy and Eva, who would become staples of later Tom Shows, it did include Liza (Morna) and an escape across the ice.

For at least a decade the most successful production was the one scripted and produced by George Aiken. Whereas in the novel, the initial conversation between slavemaster Shelby and trader Haley focuses on Tom and then moves to Eliza, in the Aiken play, the initial characters the audience meets are George and Eliza, really shifting the emphasis from the "Tom sold to the South plot" and privileging the "Harris taking the Underground Railroad" one (Figure 13). In Act I, Scene 4, upon learning that her ostensibly benevolent master has sold her infant son, Eliza runs away and, of course, finds herself near the river. Her dialogue:

Powers of mercy, protect me! How shall I escape these human blood-hounds? Ah! the window —the river of ice! That dark stream lies between

me and liberty! Surely the ice will bear my trifling weight. It is my only chance

of escape—better sink beneath the cold waters, with my child locked in my

arms, than have him torn from me and sold into bondage. He sleeps upon my

breast—Heaven, I put my trust in thee! [(Gets out of window.)]*

What happens with this section of the script is demonstrative of most of the modifications to the novel made for the stage. Recall that Stowe, in the portion of the novel quoted above, depicts Haley's pursuit as "like a hound on a deer." For the early stage versions, Aiken and others have Eliza refer to her pursuers as "human bloodhounds." As Tom Shows increased in popularity during the late nineteenth century, producers needed to continually improve their production values for increasingly savvy and familiar audiences. At the very least, the 1875 Tom Shows had to be more exciting than the 1874 ones. Sometimes more than one Tom Show was playing in the same city at the same time. So by the 1880s, the actresses playing Eliza were being chased, not just by actors playing Haley and Sam but by dogs, by real dogs (Figure 14). In the ads for then next couple of decades, promoters boasted "real bloodhounds" on stage and claimed to have more of them than last year's or a competititor's show (Figure 15). This kind of embellishment characterized all aspects of the play.

By 1879 there were at least forty-nine traveling companies performing Uncle Tom's Cabin in the United States. By some estimates there were hundreds by the turn of the twentieth century. Well into the twentieth century, Uncle Tom's Cabin remained ubiquitous. In a 1916 Los Angeles Times blurb, the readers learn that Herman Erb of Appleton, Wisconsin, saw "Uncle Tom's Cabin" for the sixty-ninth time recently.* He had not missed the play in more than thirty-five years, and although 72 years old, he says it grows on him each time he sees it. In 1923 Arthur B. Maurice noted that "Every night, somewhere in the land, an audience is moved by the spectacle of Eliza crossing make-believe ice; and of the bloodhounds in pursuit; of Little Eva dying; of Topsy who had never been born but just growed; and of Uncle Tom suffering under the lash of Simon Legree."* In conjunction with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the novel, a Los Angeles Times reprint of a Kansas City Star article observed,

The stage career of Uncle Tom began seventy-five years ago. Since that time there has probably not been few days—possibly not even one—on which the play has not been presented somewhere in the world, and there have been long periods in which numerous companies have played it simultaneously in several countires and not infrequently from two to five such companies have been rivals in a single city. Companies playing in tents, on steam boats and in the summer months when almost every other kind of play has been withdrawn.*

|

DETAIL: CLICK

IMAGE TO ENLARGE

DETAIL: CLICK

IMAGE TO ENLARGE

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

DETAIL: CLICK

IMAGE TO ENLARGE

|

|

SUCCESS

How can we explain the popularity of the Tom Shows in general and the Eliza crossing the ice plot line in particular? What was in the content of the play that inspired people to return year after year? Why would theatre-goers forego a new play they hadn't seen, and buy tickets to take in one so familiar? As a scripted rendition of an authored text, Uncle Tom's Cabin on stage and the Eliza scenes aren't authentic folklore, but the multiple performances and versions make it folkloric. In an interesting new book, business researchers Chip and Dean Heath, authors of Made To Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die, propose marketing strategies based on their identification of common elements in intractably popular conspiracy theories, urban legends, and hoaxes.* Their theories illuminate a study of Uncle Tom's Cabin. The Eliza scenes possess all six of the components of their SUCCESS formula. The Heaths maintain that "sticky" ideas are simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional stories.

So let's look at the Underground Railroad plot. It is simple, concrete, and emotional story, an infant has been sold and his hard-working mother wants to protect him. Its climax really provides the unexpected and emotional elements. How could we expect a frightened slave woman to risk her baby's life by crossing a partially frozen river? By the time she reaches this point, the audience has become emotionally invested in her, she is a loyal Christian servant, a dedicated wife, a proud mother. Had her husband been in a less abusive slave situation and her master not have sold her child, she would have contentedly stayed on at the Shelby plantation as a slave. The horrors of slavery had driven her to set off for freedom. Some might want to make the case that the story is not credible, but rather incredible, that no real woman could have successfully carried an infant across a partially frozen river. But recall that Stowe did base this plot line on a real slave woman whose story of a similar escape was documented. In the stage and movie versions she is being pursued by literal animals, ferocious bloodhounds are ready to drag her and her child back to slavery. Taken together—the simple, concrete, emotional, unexpected, credible story that is Eliza, that is indeed all of Uncle Tom's Cabin, all of these elements add up to a story that stuck.

|

|

The Fall of Eliza Harris

Although playwrights adapted the story to suit their purposes, no playwright was foolish enough to have Eliza and her infant fall into the ice and drown. But with the advent of the civil rights movement, Eliza did fall from grace as did Uncle Tom's Cabin. Why did the story stop sticking?

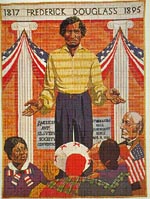

I think the answer to that question can be found by comparing Eliza's Underground Railroad story to the next one that stuck, that is currently sticking, about the Underground Railroad. On November 3, 2006 the New York Times published what I'm sure the editors thought was a benign editorial about a memorial to Frederick Douglass, probably the most well-documented individual ever to have used the underground railroad (Figure 16).* Describing a memorial being constructed in Harlem to honor Douglass, Francis X. Clines, notes:

His statue likeness, noble and powerful as the man, will peer forth at the skyline. The setting includes a 60-feet-long laser-lit fountain, flowing with the waters of freedom, and an array of the quilted code symbols that were one of the ingenious secrets of the slaves' escape north. Strategic quilts, harmlessly hung out to air along the routes to liberty, offered instructions and maps to knowledgeable slaves on the run. Their innocent symbols—wheel, crossed wrenches, bear's paw, log cabin, child's shoofly—were guides and cautions, just as patterns of knots marked

mileage.*

The New York Times immediately began to hear from historians who were quick to point out that there was no evidence that Frederick Douglass, or any other fugitive slave for that matter, had interpreted quilt codes to get to freedom. Similarly, quilt-based on-line discussion groups and newslists received numerous postings from textiles scholars bemoaning the news that on the one hand, as august a publication as the New York Times had repeated the story of the quilt code and also that a permanent memorial to the alleged code was already well under construction. The eminent Douglass scholar, David Blight, currently on the faculty of Yale University, was the most frequently quoted historian on the controversy. Commenting on his dismay over the quilt component of the memorial he wrote, "I simply object to associating Frederick Douglass in a major public memorial with such a legend," "Frederick Douglass never saw, nor did he even hear of, a quilt used to signal a runaway slave like himself, on his or her desperate journey to freedom."*

Blight is actually one of the first scholars to use the term "legend" to refer to the stories of the underground quilt code, and I agree with that assessment. It is what folklorists refer to as an urban or contemporary legend. It is a narrative that is told as true but that lacks reliable standards of evidence. Think about the stories in which it is alleged that sadists put razor blades in apples at Halloween or that gangs have an initiation ritual requiring them to kill or rape motorists who signal to them that they haven't turned on their headlights. Several common denominators are evident in these texts and the ways in which they are communicated. Multiple versions of them exist, and they circulate orally, in print, and on the Internet.* Once scrutinized (usually by those beyond the susceptible audience) the evidence of the truth claim embedded in them is often, but not always, found weak. Nonetheless, these legends continues to circulate, drawing in new believers while those investigators who have think they have debunked a cycle of texts fret about the susceptibility of believers. In fact, often when individuals within the sympathetic group hear evidence undermining the truth claim in a legend, they accept that as evidence of the story's veracity.

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

|

|

Although the texts exist in multiple variations one book, the provocatively-titled 1999 publication Hidden in Plain View: The Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad is always at the epicenter of this controversy. According to co-author Jacqueline Tobin, Ozella McDaniel Williams reinforced her sales pitch of an antique black made quilt by offering an elaborate account of a quilt code used by slaves on the Underground Railroad. William's meandering tale claimed that familiar quilt blocks such as the Bear's Paw, the Monkey Wrench, Drunkard's Path, and Dresden Plate were assembled in ways interpretable to conductors and fugitives needing a map to guide them out of slavery. Tobin consulted with African-American art historian and quilter Raymond Dobard, who agreed that Williams' story was plausible and that together, Tobin and Dobard were the right pair to write a book about the code and the Underground Railroad. Acknowledging that their sources were limited, the co-authors do inform their readers that their evidence comes from oral testimony handed down from one generation to the next in one family, "Ozella received it [story of the code] from her mother, who received it from Ozella's grandmother."* Another version of the story that still circulates and predates Hidden in Plain View alleges that quilts were used as signals of a safe house. The most common version of this text claims that fugitives and Underground Railroad conductors used log cabin quilts as signals of a safe house. The presence of a log cabin quilt on a clothesline confirmed to the fugitive that s/he had reached the right house (Figure 17). But the presence of maps or codes embedded in the quilts dominate this discourse. To many readers—ardent quilt fans, African-Americans and others dissatisfied with the ways in which many historians and others characterize slavery—these stories really resonated, they stuck.

But not all readers were favorably impressed by Hidden in Plain View and the research that undergirds it. Historians, folklorists, and other scholars who work with oral testimony were disappointed that the authors relied on only one informant, and didn't take any steps to corroborate her story with other extant sources. Dobard and Tobin didn't seek out other black men and women of Williams' generation whose ancestors might have passed on stories about the Underground Railroad or probe written documentation that might have validated or disputed Williams' family recollections. Quilt scholars were dismayed by the lack of rigor the authors employed in matters related to textile history and scholarship. One concerned textile scholar summarizes, ". . . professional historians and an increasingly vocal group of laymen and

women—students of quilt history and the history of African-Americans—have decried the 'Quilt Code' as without factual basis, accusing its proponents of sloppy scholarship at best and sheer hucksterism at worst."* Dobard and Tobin didn't offer any valid explanations as to how quilt motifs and fabrics unknown in any other antebellum quilts were used in the quilt code, particularly since there were no concrete examples of any real quilt actually containing such a code itself. Some of the sources that Dobard and Tobin did cite were unorthodox at best; they even footnote Sweet Clara and the Freedom Train, undoubtedly one of the first instances in which a children's picture book is used for the purposes of scholarly verification.

But Hidden in Plain View's appeal seems to have suffered very little as a result of the web pages, conference papers and articles that question its veracity and negatively criticize the research skills of the co-authors. Any bookstore with a sizeable inventory of books on African-American culture or quilt studies is likely to have copies of Hidden in Plain View. Numerous individual quilters have paid tribute to the courage of those who traveled by the Underground Railroad by making quilts that encompass the motifs associated with the code. Ironically, as more and more research fails to unearth any concrete connections between quilts and the Underground Railroad, the more resilient and accepted the original accounts of a connection have become.

This pattern is, of course, consistent with the way in which contemporary legends circulate. In Made To Stick, co-author Chip Heath credits his study of urban legends as very influential in his thinking about beliefs come to be embraced. With the narratives regarding quilt codes, we see the

SUCCESS formula at work. The tales of escaped slaves reading quilts are simple and concrete. It contains the unexpected . . . a quilt disguised as a map, who would have thought it? Quilts themselves have become inherently emotional totems and in this story the listener/reader can admire the resourcefulness of the clever fugitives who use such a sentimentally charged artifact for good. For African-Americans in particular, usually forced to grapple with assumptions that slaves were uneducated and powerless, the quilt code offers ancestors who emerge as smart and powerful.

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

|

|

Conclusion: Back To Eliza

For approximately one century, the harrowing escape constructed by Harriet Beecher Stowe and the producers of the Tom Shows stuck; in fact, it worked better than any of the true stories. It personalized both the predicament faced by the thousands of black men and women who risked their lives in pursuit of freedom as well as the unfailing determination of those who pursued them. One of the most compelling arguments used by abolitionists against slavery always had been the peculiar institution's devastating impact on families. Even before they ran away, George, Eliza, and Harry were unable to live together. But they had done all the right things, all the things good Christians are supposed to do. George had bettered himself to the point of being essential to his owner's success. Eliza was unflinchingly loyal to her mistress. Both were light-complected, thereby leading to the unfortunate implication that humans with "white" blood were subject to slavery. Their ignoble pursuers, complete with belligerent dogs in the stage versions, symbolized the capitalistic excesses endemic to the Southern economy.

But by the late twentieth century, a different kind of Underground Railroad story was needed to satisfy more comprehensive understandings of the circumstances of slaves and slave owners. The heroes and heroines did not undergo a complete makeover; in the quilt code stories, we do see some traits reminiscent of the Stowe characters. The African-Americans who pursue freedom are still hard-working, courageous, and Christian. Many of them are female, even young girls. This development makes sense when we consider that the modern women's movement followed on the heels of the modern civil rights movement. Both movements sought to undermine the image of slaves/women as powerless victims and to reinforce stories that stress the intelligence required of nineteenth-century blacks. In the quilt code stories, leaving their shackles behind requires the slaves to outsmart, not outrun, the more powerful slave catchers. Their "weapon" is an unorthodox one, a product of women's work, an innocuous quilt, which provided a path to freedom. Illiteracy isn't an impediment to a successful escape, because the cunning fugitives know how to read the codes embedded in the quilts. The evil slave catchers play a much less dominant role, and instead of coming across as ruthless ogres, they are depicted as hapless fools, too ignorant to even realize that mere quilts are signaling the way from their plantations to the free enclaves of the North. Whereas luck and stamina were essential characteristics for the Eliza and George in Uncle Tom's Cabin and the stage shows, mental prowess is celebrated in quilt code/Underground Railroad legends. All in all, these post-modern stories about plucky and confident fugitives, "smart" quilts, inept slave catchers, and astute abolitionists are eminently likeable, they stick for contemporary audiences. The quilt code stories affirm a view of slavery in which the slaves have agency and control—important attributes to post-civil rights movement African-Americans. These are stories of liberation, not escape.

|