|

|

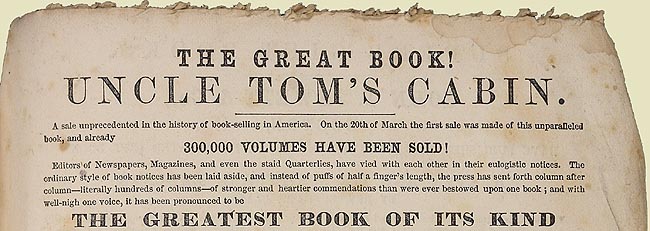

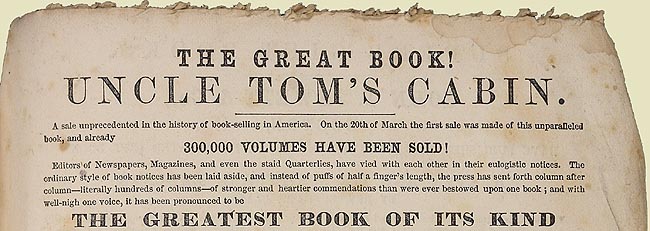

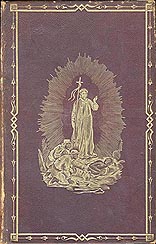

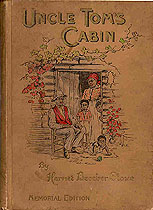

In early 1851, when Harriet Beecher Stowe first imagined writing "some sketches which should show the world slavery as she herself had seen it," [FIGURE 1] she was already an established author.* She had been writing and publishing domestic sketches and stories for many years, since 1834, and a small collection of these had been published as The Mayflower in 1843 over the imprint of Harper & Brothers. Slavery had not been a subject that she had dealt with in her writings, however, but the passage the preceding fall of the Fugitive Slave Act, which enjoined all American citizens, North and South, to act in support in that "peculiar institution" of chattel slavery, [FIGURE 2] meant that the subject was very much on her mind. At the time, she had been contributing sketches to a moderate anti-slavery newspaper, The National Era, published in Washington, D.C., and on 9 March 1851 she wrote to its editor, Gamaliel Bailey, as follows: Mr. Bailey, Dear Sir: I am at present occupied upon a story which will be a much longer one than any I have ever written, embracing a series of sketches which give the lights and shadows of the "patriarchal institution," [FIGURE 3] written either from observation, incidents which have occurred in the sphere of my personal knowledge, or in the knowledge of my friends. I shall show the best side of the thing, and something faintly approaching the worst. Up to this year I have always felt that I had no particular call to meddle with this subject, and I dreaded to expose even my own mind to the full force of its exciting power. But I feel now that the time is come when even a woman or a child who can speak a word for freedom and humanity is bound to speak. . . . My vocation is simply that of painter, and my object will be to hold up in the most lifelike and graphic manner possible Slavery, its reverses, changes, and the negro character, which I have had ample opportunities for studying. There is no arguing with pictures, and everybody is impressed by them, whether they mean to be or not.*The result would be that remarkable phenomenon, Uncle Tom's Cabin. It would be unlike any other book published in the 19th-century United States: "The Greatest Book of Its Kind" [FIGURE 4] as John P. Jewett, its original publisher in book form, would advertise it.* At the time Stowe wrote to Bailey, she imagined that her sketch would be ready in two or three weeks and might extend to three or four numbers, but in the event the first installment did not appear until the 5 June 1851 issue of the National Era, and the novel would appear regularly each week, with only three omissions, until 1 April 1852.* [FIGURE 5] As a serial, the novel attracted considerable attention, but it was only when it was published as a book that it would truly take off. Plans were being made for its book publication as early as summer 1851, when Catharine Beecher, Stowe's older sister and a far more established author, approached the Boston publisher, Phillips, Sampson & Co., to enquire if that firm might be prepared to publish it in book form. That firm declined, however, believing that it would not be a success and that it might "disturb their business relations with the South."* Stowe next turned to another Boston firm, John P. Jewett & Co., which was an established publisher of many religious works representing the evangelical wing of Congregationalism. Jewett had likely met the Beecher family during his brief stint as a publisher in Cincinnati in 1844, since when he had published works by Stowe's brother, Henry Ward Beecher, and husband, Calvin Stowe, and would soon go on to begin publication of the collected Works of her father, Lyman Beecher. On 18 September 1851, the National Era announced that arrangements had been made for Jewett to act as publisher of Uncle Tom's Cabin in book form.* In September 1851, Stowe had little idea of how long the work would become, though surely it grew beyond both her own and her publisher's expectations. A final contract was not signed until 13 March 1852, only weeks before the work's completion in serial form: Stowe's husband, Calvin, was in charge of the negotiations. At Catharine Beecher's suggestion, Calvin first suggested a half-profits contract, which was highly unusual at the time, but Jewett declined, preferring the standard royalty system, which would pay Stowe a ten percent of the retail price on all copies sold. Calvin was reluctant to agree, and requested a royalty of twenty, or at least fifteen, percent, but again Jewett demurred, claiming that such a high royalty would prevent him from promoting the book adequately. Finally, after consulting with members of the Boston book trade, Calvin agreed to Jewett's terms — a royalty of ten percent — and the book was published on 20 March 1850 [FIGURE 6], twelve days before its serial publication was complete. It appeared in two volumes, with six illustrations, in a choice of three bindings: cloth at $1.50 [FIGURE 7], cloth extra gilt at $2.00 [FIGURE 8], and paper wrapper at $1.00.* |

|

|

|

|

|

From the beginning, Uncle Tom's Cabin was a hit! The initial printing of 5,000 copies was soon exhausted, and by 1 April 1852 a second printing of 5,000 had appeared. In mid-April, Jewett announced that these two printings had been sold in two weeks and added: Three paper mills are constantly at work, manufacturing the paper, and three power presses are working twenty-four hours per day, in printing it, and more than one hundred book-binders are incessantly plying their trade to bind them, and still it has been impossible, as yet, to supply the demand.*And demand did not slack off. By mid-May it was announced that fifty thousand copies had been sold, by mid-September seventy-five thousand, and by mid-October one hundred twenty thousand.* For the 1852 holiday season, Jewett prepared two new editions: three thousand copies were issued of an expensive octavo gift edition [FIGURE 9 | FIGURE 10], with over one hundred illustrations by the work's original illustrator, Hammatt Billings, that sold at $2.50 to $5.00, depending on the binding, and thirty thousand copies of an inexpensive "Edition for the Million," [FIGURE 11] printed in two columns, at 37 1/2 cents. The following February Jewett issued a German translation [FIGURE 12]. Early in July 1852, Jewett sent Stowe her first royalty payment of $10,300, followed by a similar payment at the end of the year.* Uncle Tom's Cabin was not only a success as a book, but became a phenomenon. Jewett himself started the trend in July 1852 when he commissioned John Greenleaf Whittier to write "Little Eva; Uncle Tom's Guardian Angel," which he published first as sheet music [FIGURE 13], but this was only the first of the many products that the book inspired [FIGURE 14]. Prints, pottery, games, puzzles, dolls, among other things, quickly followed, as well as numerous adaptations, condensations, responses, among many other tie-ins. The work was soon dramatized and went on to become a staple of the American popular theater. In England, the text was first published in early May and became an even greater success: it was later claimed that in September "the London publishers furnished to one house 10,000 copies per day for about four weeks" and that more than a million copies were sold there by year's end, "probably ten times as many as have been sold of any other work, except the Bible and Prayer-book."* Elsewhere, the work was also soon reprinted, both in English and in translation, and one might claim that Uncle Tom's Cabin was the world's first true blockbuster. But the book's success was qualified. By late spring 1853, Jewett had produced about 310,000 copies of Stowe's text, in various editions, but at that point demand came to an unexpected halt.* No more copies were produced for many years, and if, as is claimed, Abraham Lincoln greeted Stowe in 1862 as "the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war," the work had effectively been out of print for many years.* Jewett, who I believe played an important role in its success through his promotional efforts (he later claimed to have spent many thousands of dollars in advertising), may in the end have made very little profit from the book's publication. He was forced to suspend payment of his debts during the panic of 1857, and in August 1860 his firm ceased publishing. There is some evidence that Jewett ordered a small printing of Uncle Tom's Cabin in late 1859, though no copy of that printing can now be located.* What is certain is that in June 1860 the rights and plates of Uncle Tom's Cabin passed to another Boston firm, Ticknor and Fields, which had established itself as the leading American publisher of literary works, especially those by New England authors. This firm was, however, in no rush to put the work back in print, and not until November 1862 did it finally issued a small impression of only 270 copies. The following 5 March, Stowe signed a contract with Ticknor and Fields that guaranteed her a royalty of eighteen cents on every copy of Uncle Tom's Cabin sold as long as the copyright of the work remained in force in the United States.* With its new publisher, demand for Uncle Tom's Cabin increased slowly. During the 1860s, Ticknor and Fields produced only 7,951 copies, which earned Stowe $1,230.30 in royalties [FIGURE 15]. During the 1870s, the original 1852 plates, still in use, produced another 19,458 copies, for which the firm paid Stowe $3,463.38.* During that period, Ticknor and Fields, after the death of William D. Ticknor in 1864 and the retirement of James T. Fields in 1868, was publishing over the imprint of Fields, Osgood & Co. and, later, James R. Osgood & Co. In 1878, just as the original copyright on Uncle Tom's Cabin was due to expire unless renewed, that successor firm's senior partner, James R. Osgood, was forced to join with Hurd & Houghton to form Houghton, Osgood & Co. At this point, it was decided to cast a new set of plates, as the original 1852 plates, which had been used to produced nearly 350,000 copies and were still valued, taking into account the right to publish the work, at $4,524.60 [FIGURE 16], were badly worn and much in need of replacement.* The new edition of Uncle Tom's Cabin, first published in 1879, repackaged the novel as an American classic. A long introduction, written anonymously by Stowe, stressed the work's national and international impact, first as a force against American chattel slavery, now comfortably in the past, but also as a work that fostered Christian support to suppressed classes around the world, ironically given the failure of Reconstruction and the imminent arrival of the Jim Crow laws that would foster widespread discrimination and violence against African Americans. It was also portrayed as an American classic. Stowe's introduction is supplemented by a bibliographical checklist of foreign editions and translations that had been collected by the British Museum Library compiled by its Keeper of Books, George Bullen [FIGURE 17] — again stressing the work's status not just as an American, but as a world, classic. Twenty-eight years after its original publication and fifteen after President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Stowe's novel was being put to new uses. These new plates were used to produce Uncle Tom's Cabin in two forms: the red-line "Holiday Edition," which sold for $3.50, and the cheaper "Library Edition" for $2.00 (and, later, for a reprint issued for even less in paper wrappers [FIGURE 18]). Eventually, over 72,000 copies were printed from these plates before they were melted in 1909 [FIGURE 19]. In 1885, another new set of plates were manufactured, and these were used to produce [FIGURE 20] the even cheaper "Popular Edition" for $1.00 in cloth, and fifty cents in paper wrappers. This set of plates was still in use in 1917, by which time it had been used to print over 202,000 copies. During the second half of the nineteenth-century, Uncle Tom's Cabin again achieved broad popular appeal [FIGURE 21]: between 1886 and 1890, Houghton, Mifflin & Co. sold a total of 109,495 copies and paid Stowe $13,324.50 in royalties.* But all was not well. In March 1892, Houghton, Mifflin had a scare: an article in an obscure periodical, the National Advertiser, entitled "A Remarkable Discovery" announced that Uncle Tom's Cabin "was not, and never has been, legally copyrighted."* Discussions within the firm were already underway about just how to manage the moment in 1893 when the work would enter the public domain, but this announcement called for extraordinary measures. The firm immediately sought legal counsel and secretly sent a staff member to the copyright office at the Library of Congress to determine the true status of the work. These investigations were inconclusive but, putting a bold face on the situation, on 16 April 1892 the firm took out a full-page advertisement in Publishers' Weekly to address it: As certain statements have recently appeared in a New York newspaper which give the impression, and have created the belief in the minds of many persons, that the copyright on Mrs. Stowe's world-famous novel, "UNCLE TOM'S CABIN," has expired, or is non-existent, the undersigned hereby give notice that there is no foundation in fact for the assertions that have been made. Copyright was originally and duly issued to Mrs. Stowe; it was duly reissued to her on the expiration of the first term of twenty-eight years, as is shown by the official certificates in our possession; and it has still a considerable period to run. Mrs. Stowe's interest in the work continues without abatement, and she receives a royalty on every copy sold. Any attempt to reprint "UNCLE TOM'S CABIN" before the expiration of copyright will be illegal and an infringement on the rights of Mrs. Stowe and ourselves, and will be promptly prosecuted by us. The trade and public are hereby cautioned against buying any editions except those published by the undersigned . . .In May, Houghton, Mifflin & Co. followed up with a "Note to the Trade," in which they explained that the facts in the case of Uncle Tom's Cabin would enable the firm "to obtain an injunction against any person who shall...print, publish, sell or expose for sale any copy of said book within the term...of said copyright."* These announcements were ingenuous, however, as the true facts in the case showed that the work would enter the public domain, unprotected by copyright, on 12 May 1893, less than a year after this last announcement was published. Facing this unpleasant prospect, the firm decided to follow a strategy that it was also using for Hawthorne's Scarlet Letter, another American classic, that went out of copyright in 1892. This involved issuing new editions of Uncle Tom's Cabin in numerous formats and at a variety of prices, from cheap to expensive, in order to blanket the market — a strategy that had been pioneered by Jewett for the holiday season of 1852, when he offered the work in three editions in several bindings, recognizing that the market would sustain multiple editions that appealed to a variety of purchasers. This approach to managing sales only became standard among American publishers after the Civil War, and Houghton, Mifflin hoped that, by providing multiple editions at a range of prices, it could maintain control of the market for Uncle Tom's Cabin after it came out of copyright. Accordingly, in late 1891 the firm had issued a new two-volume deluxe illustrated "Holiday Edition," printed from new plates. At the retail price of $4.00, this was an expensive book, but a $10.00 "Large Paper" limited edition, signed by Stowe, was also issued, printed from the same plates [ FIGURE 22]. The real competition, however, would be at the lower end of the market. In February 1892, a second new edition — the "Universal Edition" — was published at 50 cents in cloth, and 25 cents in paper [FIGURE 23], and later that year plans were made for an even cheaper edition. The "Brunswick Edition," priced at only 30 cents in cloth, was finally ready in March 1893. By the time that the copyright expired just a month and a half later, 38,104 copies had been produced. Initially, Houghton, Mifflin's strategy succeeded. For many years Stowe's royalties on Uncle Tom's Cabin had ranged between $2,000 and $3,000 per annum [FIGURE 24 | FIGURE 25], but in 1892 her earnings were $6,693.77 — chiefly as a result of the recently published "Universal Edition." The publication of the "Brunswick Edition" in 1893, however, brought the sales of the "Universal Edition" to a near halt. Although 53,498 copies of the "Brunswick Edition" were sold by November 1893, its retail price of 30 cents meant that it paid a very low royalty, and Stowe's earnings from Uncle Tom's Cabin fell to only $2,407.51. Although the firm was to remain a major publisher of the work after the copyright expired, the sales of all Houghton, Mifflin editions fell off markedly as they had more and more to compete with a range of new editions published by firms who specialized in cheap reprints — Altemus [FIGURE 26], Burt, Caldwell [FIGURE 27], Coates, Crowell [FIGURE 28], Dominion [FIGURE 29], Donohue, Fenno, Hill, Hurst [FIGURE 30], Lupton [FIGURE 31], McKay, Mershon, Neely, Page, People, Rand, Routledge, Warne, and Ziegler — editions from a representative selection of the publishers of cheap books operating at the turn of the century that are listed in The United States Catalog: Books in Print, 1899.* But there were surely others, including copies issued by the Syndicate Publishing Co. [FIGURE 32] and John C. Winston & Co. [FIGURE 33], both of Philadelphia. Stowe's earnings from the authorized editions dropped accordingly: in 1894 her royalties on the work fell to $903.59; the following year to just $696.56 [FIGURE 34]. |

|

|

|

|

|

By the end of the nineteenth century [FIGURE 35], Uncle Tom's Cabin was widely available in a multitude of editions, many very cheap indeed, but who could have forecast its fate during the twentieth century? From American classic — a work of genius, as George Sand had called it — it came to be viewed as an embarrassment: racist, sentimental, and poorly written. Only recently have scholars begun the task of reassessing its place in American literary culture, and it remains to be seen just how it will be evaluated as we continue, during the twenty-first century, to struggle with our vexed history of race relations in the United States. |

| © 2007 Michael Winship. This essay derives from a presentation at the June 2007 Uncle Tom's Cabin in the Web of Culture conference, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and presented by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center (Hartford, CT) and the Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture Project at the University of Virginia. |