[from] PLACES OF PUBLIC AMUSEMENT.

THEATRES AND CONCERT ROOMS.

...The theatre is one of the greatest anomalies of modern civilization. It has been an established institution in all civilized countries, in the face of an opposition lasting through 500 years, and it still stands. Next to the sports of the chase it is the oldest of all human recreations, and claims for its votaries the loftiest geniuses that have blessed mankind. The instincts of the people demand its pleasures, and it will find a footing wherever it is not excluded by law. The taste for the stage is not merely a love of tinsel and inexplicable dumb show--it is the universal desire to see the bright side of the world, and to travel out of ourselves into the airy regions of poetry and romance.

The persecution it has met, has been deserved, where it fell upon the immoralities unhappily united with it: but the undiscriminating hostility to all dramatic representations of human life, as something iniquitous per se, is mere folly, inexcusable were it not for something worthy in the feeling from which it sprung. Had the stage been rescued to the purposes of virtue, instead of having suffered outlawry among the good, a powerful instrument would have been saved to the better side. Not only for the purposes of amusement, but of mental culture, dramatic show is a natural and efficient means. Regardless or thoughtless of this, good men have let it decline to base uses and then blamed the evil which in some measure at least, they might have prevented. Were every delicious taste or art abandoned on the same ground as the drama, our life would be bereft of the benefit and solace of the whole of them. There are great difficulties, no doubt, in giving to the stage a high and pure character--but are they insuperable? Is there any reason why this as well as any other natural taste may not be purged and made a "minister of grace?" If there be, still let us discriminate between the thing itself and our own weakness.

It is a strange circumstance that while music, painting, poetry, elocution, and dancing, are not only considered as harmless,

but as elevating and beneficial arts, in themselves, yet, when they are all combined in the production of a drama they are

regarded as fit only to be anathematized. The church, too, combines in its ceremonials all these arts but the last, and, in

all Catholic countries eclipses the feeble attempts of the stage, in their combination to dazzle the senses and thrill the

imagination. Of course there can be no comparison between the theatre and the

Church, because it is the province of the one to amuse, and the other to instruct the believer in the solemn mysteries of eternal salvation. The stage, too, professes to be moral, and the punishment of vice is the inevitable end of all dramas. There is no such lusus as an immoral drama. It is the delight of the coarsest natures to see poetical justice dealt out to the wicked, and the sufferings of the virtuous from the great staple of all tragedies. There is nothing that so certainly commands the tears of an audience, as the undeserved calamities of the innocent. One of our theatres has been reaping a harvest of nightly benefits by exhibiting the untimely death of a little girl, and the hardships of a virtuous slave. The public go to the National Theatre, in one of the dirtiest streets of the city, where they sit in not over-clean boxes, amid faded finery, and tarnished gilding, to weep over Little Eva and Uncle Tom. It takes us back to the days Aeschylus, and convinces us that the love of the drama is as strong as it ever was, and that it must remain for ever while men have hearts capable of being moved by human suffering. The descent from Prometheus to Uncle Tom, dramatically considered, is not a very violent one, nor so long as some may imagine.

...The theatrical business in New-York has, until within a short time, been almost entirely in the hands of Englishmen, and even the majority of the players are still foreigners, and it is doubtless owing in a great degree to this fact, that the stage has continued to lag in the rear of all other institutions on this side of the Atlantic; it has not appealed to the sympathies and tastes of the people; the actors have been aliens, and the pieces they performed have all been foreign; to go inside of our theatres was like stepping out of New-York into London, where the scene of nearly all the comedies presented is laid. English lords and leadies, English squires, clodhoppers, and Cockneys; English rogues, English heroes, and English humors from the staple of nearly all the

plays put upon our stage. The actors and actresses speak with a foreign accent and all their allusions and asides are foreign.

The only places of amusement where the entertainments are indigenous are the African Opera Houses, where native American vocalists,

with blackened faces, sign national songs, and utter none but native witticisms. These native theatricals, which resemble

the national plays of Italy and Spain, more than the performances of the regular theatres, are among the best frequented and

most profitable places of amusement in New-York. While every attempt to establish an Italian Opera here, though originating

with the wealthiest and best educated classes, has resulted in bankruptcy, the Ethiopian Opera has flourished like a green

bay tree, and some of the conductors of these establishments have become millionaires. It was recently proved that one of

the "Bone soloists" attached to a company of Ethiopian minstrels, had spent twenty-seven thousand dollars of his income within

two years. It is surprising that the managers of our theatres do not take a hint from the success of the Ethiopian Opera,

and adapt their performances to the public tastes and sympathies. The manager of the National Theatre, one of the least attractive

of all the places of public amusement, has made a fortune by putting Mrs. Stowe's Uncle Tom upon his stage. Uncle Tom, as

a drama, has hardly any merit, it is rudely constructed, without any splendors of scenery and costume, or the fascinations

of music; the dialogue is religious, and the Bible furnishes its chief illustrations; but it is American in tone, all the

allusions have a local significance, and the sympathies of the people are directly appealed to. The result is an unheard-of

success, such as has never been accorded to any theatrical performance in the New World. The manager of the National Theatre

is himself an American, and nearly all his corps of actors are also natives, and though he only aims at the tastes of the

lowest

classes of people, yet his theatre has been daily and nightly filled with the élite of our society, who are willing to endure all the inconveniences which a visit to the place imposes for the sake of enjoying an emotion, such as neither the preaching of their clergy, nor the singing of Italian artists could create. A slight reaction of popular favor towards the theatre has been caused by the presence of Mr. Bourcicault among us, the author of London Assurance. To witness the first representation of a new comedy by a popular English dramatist has attracted a class of people to the theatre who have not been in the habit of frequenting it.

...There are innumerable places of recreation in such cities as New-York, which are not properly entitled to be classed under the head of places of public amusement, which we are considering now. The theatre has always been, and still is, the principal place of public amusement, and, though its character has greatly changed, and its frequenters are no longer of the class who once gave it its chief support, it occupies too prominent a place in the social organization of our great towns to be overlooked by professed moralists and religious teachers. Its existence, and the fact of its being frequented by immense numbers of people whose morals need looking after, should be sufficiently strong reasons for the clergy, and all others who are by virtue of their office public teachers, to exert themselves to render it as little harmful as possible. To stand outside and denounce the theatre without knowing any thing of its interior is not the true way to improve it. The representation of moral, and even religious plays has been found not only very effective upon the audiences who attend upon them, but profitable to the manager who brings them out.

As religious novels form a very considerable part of the popular books of the day, we see no reason why religious dramas should

not also form an important part of theatrical entertainments. The fact that such a drama as Uncle Tom's Cabin can be represented

two hundred nights in succession, at one of the lowest theatres in New-York, converting the place into a kind of conventicle

and banishing from it the degraded class, whose presence has been one of the strongest objections to the theatre which has

been made by moralists,

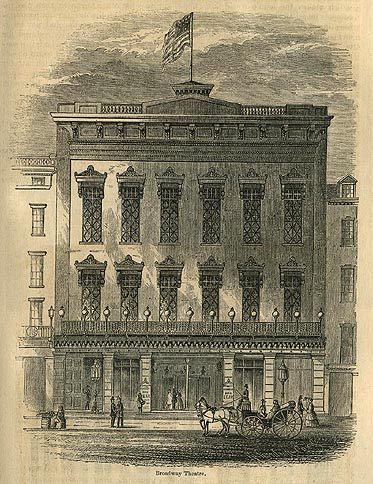

is sufficient to show that religious plays, like religious novels, may be pressed into the service of education with powerful effect. It is stated by Mrs. Mowatt, in her autobiography, from which we have already quoted, that in the catalogue of English dramatic authors there are the names of two hundred clergymen. But we imagine that none of these have written any religious plays. There are six regular theatres in New-York, which are open nearly every night in the year, excepting Sundays, for dramatic representation, and the public that sit night after night with a fortitude and good nature to us incredible, to see the School for Scandal and the Lady of Lyons would be but too happy to vary their amusements by a religious drama, if it were only new and intelligible. The chief of our city theatres, which claims to be the Metropolitan, since the destruction of the Old Park, is the Broadway. It is a very large house, capable of seating some 4300 persons. It was built by Col. Alvah Mann, a great circus proprietor, who ruined himself by the speculation, and is now the property of Mr. Raymond, another millionaire of the ring. Broadway is a "star house," and depends more upon the attraction of a single eminent performer than upon the general character of its performances, or its stock company; and it is at one time a ballet, another a tragedian, again an opera, then a spectacle, that forms its attractions. Forrest has here appeared one hundred nights in succession; here too Lola Montez made her debut in America, and any wandering monstrosity is seized upon by the manager to secure an audience. The regular drama, excepting with the attraction of a star, is found to be a regular bore to the public, and a regular loss to the house. The manager of the Broadway, E. A. Marshall, Esq., is neither an actor nor a dramatist, but simply a man of business; and, besides the Broadway Theatre, he is also proprietor of the Walnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia, and of the theatres in Baltimore and Washington. Neither the exterior nor interior of this house is at all creditable to the city; it has a shabby and temporary look externally, and the ornamentation of the auditorium is both mean and tawdry. No class of people seem to frequent it for recreation but only to gratify an excited curiosity.

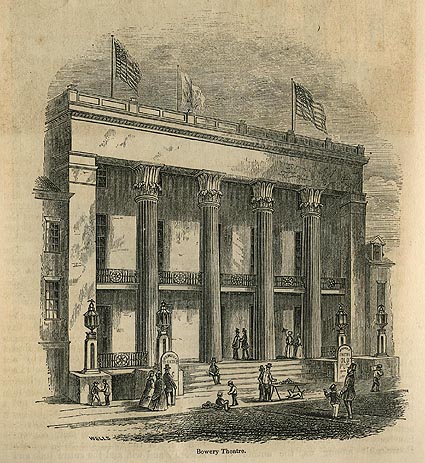

The "Bowery," which is the oldest of all the theatres in New-York, is about the same dimensions as the Broadway, but has a stage of much greater depth, and better adapted to spectacle. It is frequented chiefly by the residents of the eastern side of the city, and its pit is generally filled with boisterous representatives of the first families in the city--that is, the first in the ascending scale. The performances at the Bowery are, of course, adapted to the tastes of its audiences, who have a keen relish for patriotic devotion, terrific combats, and thrilling effects, and are never so jubilant as when suffering virtue triumphs over the machinations of persecuting villainy. It was for such audiences as these, with a slight infusion of better natures, that Shakspeare wrote his dramas, and for whose amusement he was willing to personate the humblest of his creations. The present edifice is the fourth that has been erected on the same ground, since the first one was erected in the year 1826, the others having been destroyed by fire. The late proprietor of the Bowery Theatre amassed a fortune here, and left the establishment to his heirs, to whom it now belongs. It is understood to be a very profitable concern, as it has been from its first erection. It was in the Bowery Theatre where Madam Hutin, the first opera dancer seen on this side of the Atlantic made her debut, and where the first ballet was performed, one of the troupe being the then unknown Celeste. It was here, too, that Malibran made her first appearance on the stage after her unfortunate marriage, and filled the house with the beauty, fashion, and intellect of the city. Such audiences have never since graced its pit and galleries. It was on the stage of the Bowery that Forrest achieved his greatest triumphs, and laid the foundations of his fame. But it is long since stars of such magnitude have shed their sweet influences on Bowery audiences.

Niblo's is not, strictly, a theatre, but a show house, open to any body that may choose to hire it. It is one night a circus,

another an Italian Opera House; then a dramatic temple, and then a lecture room. It is called a "garden," but it is one of

the roomiest, best constructed, and most convenient of all the places of amusement in the city, and is unexceptionable in

its character. Its interior decorations are very inferior to the other theatres, but it has the great advantage of being clean

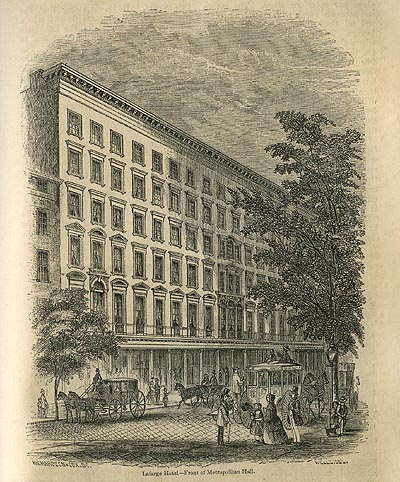

and well ventilated. The entrance to it, through the Metropolitan Hotel, is extremely elegant and capacious. Under the same

roof, within the walls of the same hotel is Niblo's Saloon, a splendid room used for concerts and balls. The whole ground

now covered by the Metropolitan Hotel was once Niblo's Garden, and the theatre was merely an appendage

to it to draw to the refreshment tables.

There are two theatres in New-York, and but two which are devoted exclusively to the performance of the regular drama; these are the Buton's in Chambers-street, and Wallack's on Broadway. Burton's Theatre was, originally, a bath-house, and was afterwards turned into an Italian Opera House, in the management of which a good deal of money was lost, and Palmo, the proprietor ruined. Burton then took possession of it, and made a fortune. It was the first instance in which a theatre in this city had fallen into the hands of a manager of scholarly attainments and artistic instincts, and the result of his management shows what may be effected by talent turned in the right direction. Mr. Burton has not only enriched himself, but has done the public a service by affording them a place of harmless and elevating amusement. One of the first pieces that he put upon his stage was Milton's Comus, which gave the public assurance that the new manager was a person of education and refinement; and the uniform good judgment shown by him in the pieces he has selected, and the superior manner in which they have been costumed, have made his theatre a superior place of intellectual entertainment for people of educated tastes. Mr. Burton is one of the best low comedians on the stage, and is, himself, one of the strongest attractions of his theatre. But, like a true artist, he never hesitates to take a subordinate part, when it is necessary to give completeness and effect to a performance. He has a devoted attachment to his art, and goes through with his nightly performances, sometimes appearing in three different pieces, with a degree of vigor, and careful attention to all the minute accessories of his part, which we could only look for in an enthusiastic acolyte in the temple of art. Mr. Burton is an Englishman; but, unlike most of his countrymen, he left his native country behind him, when he crossed the Atlantic, and became thoroughly American in his feelings. He was bred to the profession of a printer, and, after his arrival in this country engaged in several literary enterprises. He established the Gentleman's Magazine, now called "Graham's."

Wallack's Lyceum, in Broadway, is an exceedingly elegant little house, the style of the interior decoration is in excellent taste, and the effect of a full house is light, cheerful, exhilarating, and brilliant. James Wallack, the manager and proprietor, is the head of a large family remarkable for the profession of theatrical talent. He was a celebrated actor in London more than thirty years ago, and is still one of the best players in his line,--the genteel heroes of melo-drama,--on the stage. But he rarely makes his appearance before the foot lights. Wallack's Lyceum is Burton's without Burton. Great attention is always paid to the production of pieces at this brilliant little house, and the costumes and scenery form an important part of the attraction. English comedy and domestic dramas form the chief attractions at Wallack's, and the house is generally full. The utmost order and decorum are maintained, both at this house and Burton's, and every thing offensive to the most delicate taste carefully excluded from the stage.

The National Theatre in Chatham-street has long been the resort of newsboys and apprentices, and the style of performances has been very similar to those of the "Bowery;" but, in a happy moment, the manager, a good natured native whom they call Captain Purdy, put Uncle Tom's Cabin upon his stage and at once raised his fortune and changed the character of his house. As it has played this piece twice a day for nearly six months, and is now the family resort of serious family parties, it would be rather hazardous to predict what its future course may be; the old Chatham Theatre was converted into a chapel, and Captain Purdy's is half way towards the same destiny.

Attached to Barnum's Museum there is a large, well arranged, and showily decorated theatre for dramatic representations, where domestic dramas of a moral character are performed, and a version of Uncle Tom adapted to Southern tastes has been a long time running. The "St. Charles," is a small theatre in the Bowery which was built for an actor named Chanfrau, who was the creator of the universally recognized character of Mose, the type of New-York gamin.

The Italian Opera House in Astor Place has been adapted to the uses of the Mercantile Library Association; and the new opera house in Irving-place, which bids fair to be one of the most magnificent structures devoted to music in the world, is not yet sufficiently built to be described; but we shall describe it hereafter.

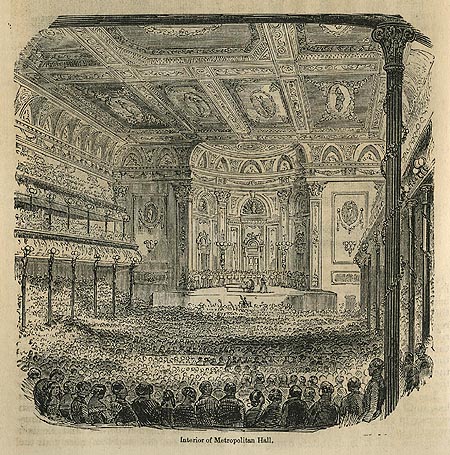

Since we commenced writing this article the most beautiful and spacious place of popular recreation in New-York has been swept

out of existence by one of those sudden and disastrous conflagrations which have earned for New-York the appellation of the

City of Fires. Metropolitan Hall,

which was unrivalled for its extent and splendor by any concert room in the world, together with the superb marble-fronted hotel in which it was inclosed, with all their wealth of embellishment and taste, the embodied forms of labor, genius, and skill were suddenly whiffed out of existence on the morning of the 8th of January. The engravings which we have the good fortune to possess of these superb structures are all that now remain, but the memories of those ornaments of our city.

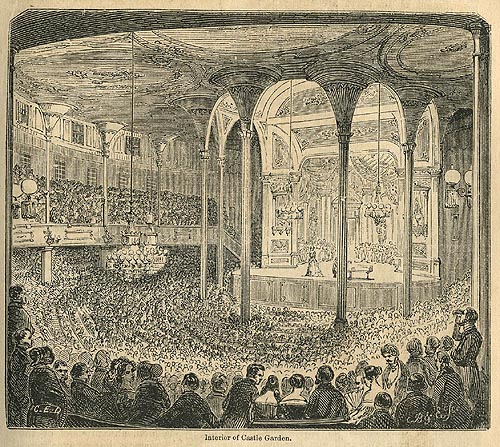

Castle Garden, the unique, remains, where opera, music, and the drama are presented by turns. It is a hall of unequalled advantages for public exhibitions, which was originally a fort, but has long been appropriated to the refining arts of peace.

The Ethiopian minstrels have become established entertainments of the public, and among them are three permanent companies in Broadway; the Buckleys, Christy's, and Wood's, where the banjo is the first fiddle, and the loves of Dinah and Sambo form the burthen of the performances.

The Italian Opera, too, is now an established institution in the New World, but it leads a vagabondish kind of life at present, and has no permanent house of its own, although one is erecting for it. We are neither wealthy enough nor sufficiently educated in music to monopolize an Italian troupe at present, but are compelled to share this luxury in common with out neighbors of Boston, Philadelphia, Havana, Mexico, Valparaiso, and Lima. The Italian Opera is the highest order of theatrical entertainment, and demands a class of educated and wealthy people for its proper support more numerous than we have yet been able to boast of. There are never more than half a dozen good singers before the public at a time, and in competing for their services, we have to contend with, not the people of other cities, but with their monarchs, the Emperor Nicholases and Emperor Napoleons, who never hesitate to spend the money of their subjects to purchase pleasures for themselves.

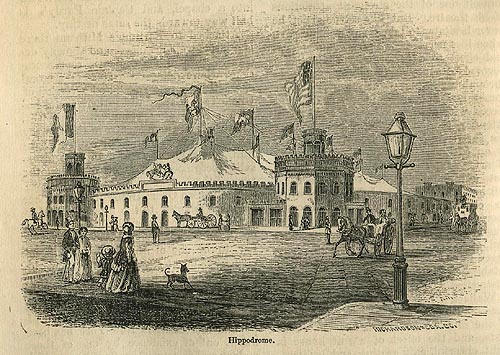

The circus is still the most popular of public amusements, and it is conducted on a magnificent scale as a regular business speculation by enterprising citizens. The most famous riders now in Europe are graduates of the American ring. The Hippodrome, in the Fifth Avenue, was an attempt to transplant Franconi's from Paris. But the Hippodrome was too exotic to thrive in our climate, and, after a season of doubtful success, it has closed probably for ever.