CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE

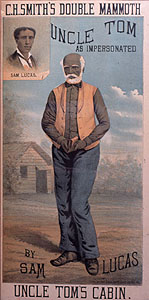

The best-selling 19th-century American novel was also the 20th century's most frequently filmed American book. Even if you don't count comedies like Topsy and Eva or Uncle Tom's Gal, or cartoons like Uncle Tom's Cabana, or the more recent made-for-TV version, the nine films called Uncle Tom's Cabin made between 1903 and 1927 still hold the record. These were all silent movies, and five of them, like so many other movies from that era, have completely disappeared. We'll probably never be able to see, for example, Thanhouser's 1910 adaptation, in which Tom apparently becomes an active accomplice in Eliza's escape. Or Paramount's 1918 production, which featured one actress, Marguerite Clark, playing both Topsy and Eva (left). Of the four films we can still see, three survive only in abridged versions. Two survive at all only because they were re-released more than a decade after they were made, in order to take advantage of the publicity surrounding Universal's 1927 big-budget adaptation. One of those, Vitagraph's 1910 Uncle Tom's Cabin, was the first 3-reel movie ever made, but the Empire Safety Film Company used only about half of it in the version they distributed in the late 1920s for home viewing. And at least one scene was cut from the 1914 World production, the first feature film to star an African American, when it was similarly re-released in the late Twenties. The surviving copy of Universal's Uncle Tom in the Library of Congress is actually the version the studio prepared a year after the film's first release, featuring a sound track with "synchronized" music and sound effects. It's at least three reels shorter than the movie audiences at New York's Central Theater saw when the film opened on November 4th, 1927.

So the one silent Uncle Tom's Cabin that looks the same to us as it did to the people who originally viewed it is the earliest adaptation: the 15-minute version Edwin S. Porter directed for the Edison Company in 1903. Just because it looks the same, however, doesn't mean we can see it the same way. One reason early film-makers were so drawn to Stowe's story was its familiarity to their audiences. The first generation of movie-goers had to learn the new technology's language of story-telling, and at the same time the technological fact that the first movies were short and silent meant that the lessons needed to be as accessible as possible. The more familiar viewers were with a film's text, the more they could fill in the missing narrative pieces for themselves. By the time the movies came along, American audiences knew Uncle Tom's Cabin as well as any primitive tribe knows its ancestral myths.