The script of this adaptation is credited to Harvey Thew and A. P. Younger, but the overall narrative seems to have been Pollard's work. Pollard was married to Margarita Fischer, who plays Eliza here (after having played Topsy in the Imp film alongside Pollard). Their relationship may explain why so much of the movie consists of close-ups of her anguished face.

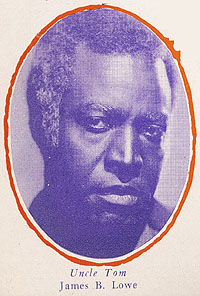

Tom is essentially a minor character -- he's on screen for less than 9 minutes altogether, and "speaks" less than a dozen lines -- but Universal nonetheless took great care with his presentation. At least, according to some scholars, the African American actor James Lowe was given the role after Pollard's first choice, Charles Gilpin, famous for his performance as Eugene O'Neill's Emperor Jones, either quit or was fired after his characterization of Tom came across as too aggressive to suit the heads of the studio.* In Universal's publicity for the film, Lowe was introduced to audiences as someone who is "respectful" and "courteous," and who realizes "better than anyone 'that never the twain shall meet'" -- a tactful way to suggest that he knows his place as a black man in a white society. On the other hand, one of the most striking innovations in this version happens at the end. Although Tom dies in conventional fashion, forgiving Sambo and Quimbo, after he's dead his spirit appears to confront Legree; there's no question that he returns to Legree to get vengeance, and in fact (as you can see in the clips) the ghost of Uncle Tom leads Legree to his death.

Pollard moved the story forward historically, enabling him to include the Civil War in it (and to have the Union Army arrive like the calvary to rescue Eliza and Cassy at the end), but the largest change is the use of Eliza and her family as the film's focal point. They do not head North to Canada, but all wind up (after a series of escapes and recaptures, separations and reunions) at Legree's. So much of the film is focused on Eliza's suffering, and then Cassy's along with her, that it could be argued this version rewrites Stowe's protest against slavery as a film about victimized women and brutal men.

The Negro press endorsed the film. Universal, however, was mainly concerned with the white public. According to Thomas Cripps,* to avoid alienating Southern white audiences, Universal repeatedly cut the film in response to complaints from their own focus groups and from southern organizations like the United Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy. The Souvenir Program, for example, includes in its account of "The Story of the Picture" the way the film was originally shot to begin with an auction sale at which a slave mother and her infant are torn apart. This scene was cut even before the N.Y. opening (so that the movie now begins with a celebration at the Shelby Plantation). After the premiere still further scenes were cut, and it was cut again for release in the southern states. (The ARTICLES & NOTICES below enable you to follow the details of this process.)

Despite these changes, the film was not successful enough to recover its cost. Its big-budget presence, though, did lead to the re-release of two of the earlier film adaptation, and helped stimulate the the nation's appetite (strong in the 1920s, stronger in the 30s) for films about "the plantation life of the glorious Old South" (as the Souvenir Program puts it).